IT would undoubtedly be the crowning engineering feat of the 21st century so far, eclipsing the likes of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge or the Three Gorges Dam (both in China).

The unlikely bearers of this crown, should they ever succeed in realising their fantastically ambitious dream of digging a tunnel under the Strait of Gibraltar, would be Spain and Morocco.

The plan to connect the Iberian peninsula with the African landmass through the waterway – 17km wide at its narrowest point – has been around since as far back as 1930.

But for most of this period it has been considered little more than a literal pipe dream, given the immense engineering complexities involved in drilling a tunnel between two separate continental shelfs.

All comparable engineering feats pale into comparison: far deeper than the Channel Tunnel, far longer than Istanbul’s Marmaray Tunnel and in far more hazardous conditions than Japan’s Seikan Tunnel.

But the Spain to Morocco tunnel took another step closer with the awarding of a €300,000 feasibility contract to German drill designers Herrenknecht through their Spanish subsidiary in Madrid, following on from a previous technical study carried out in 2021.

Famous for designing the world’s largest boring machines to dig tunnels in Hong Kong and the Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland, the longest and deepest in the world, Herrenknecht has been tasked with assessing the feasibility of drilling a tunnel from Tarifa to Tangier.

“Current deliberations assume a distance of over 30 kilometres and a depth of several hundred metres below sea level,” a Herrenknecht spokesperson told the Olive Press.

“This construction project poses extreme challenges in terms of technology and logistics – can these challenges be overcome and what solutions would be necessary?

“The feasibility study that has now been commissioned relates precisely to this.”

Herrenknecht was unable to comment further due to ‘confidentiality’ clauses in their contract. However, the list of challenges to overcome is daunting.

Almost a kilometre deep at its lowest point, the Strait is home to a soft, unstable seabed and strong currents that transfer water between the Mediterranean and Atlantic.

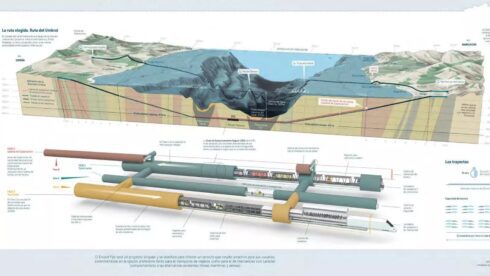

Even avoiding the worst depths, the tunnel will have to go under the Umbral de Camarinal, a giant underwater ridge in the Strait of Gibraltar around 280 metres below the surface.

At such depths, the pressure is enormous, requiring a tunnel not just deep but incredibly strong to prevent a catastrophic collapse.

Meanwhile, the tunnel may collapse anyway due to the seabed, which is made of soft clay, loose sediments, and fractured rock – unlike the stable chalk of the Channel Tunnel.

Boring through loose materials is far more difficult because the tunnel lining has to reinforce the entire structure as it is dug.

Another immediate threat to the tunnel’s integrity is the seismic activity prone to the area, magnified by the loose rock in which the tunnel would sit.

And all of this coupled with some of the fastest and strongest currents in the world.

Current plans imagine two single-track train tunnels with a diameter of 7.9 metres separated by a six-metre-wide central service tunnel running interconnected by cross-passages every 340 metres.

The total length would be 42 kilometres, with roughly 27.7 running under the water.

Early projections estimate it will cost between €5 billion and €10 billion, with some less optimistic forecasts believing it could approach €25 billion and not be ready until 2040, dashing hopes of opening the tunnel in time for the 2030 World Cup, jointly hosted by both countries.

Meanwhile, the majority of the costs will likely be put up by the respective governments of Spain and Morocco, raising the issue of whether the political will is really there for such an exorbitant and challenging endeavour.

However, experts believe the train line could carry 13 million passengers each year and stimulate economic growth in both countries.

Assuming the plan is deemed to be feasible, there is the thornier question of whether Spain and Morocco have the political will.

The two neighbours have a thousand-plus-year history as ‘frenemies’, marked not least by the multi-century reconquista and subsequent colonial relationship.

Despite these internecine struggles, the exchange of languages, cultures and indeed genetics has been constant.

A train line to connect the two through the Strait of Gibraltar is viewed as not just an economic project at one of the world’s key global choke points, but also a symbol of rapprochement and common brotherhood.

Yet, for all the feel-good joy of undertaking such an ambitious project, there are doubts over the need, the will and the financing.

At the rate public budgets balloon, if the starting figure is €8 billion then the final figure is likely to be €24 billion.

Would middle-income Morocco, and lower-upper income Spain really be willing to chuck a significant proportion of their GDPs into the project?

However, before any of that can be considered, we must await the result of the feasibility report, due out in June this year.

Click here to read more Other News from The Olive Press.

In addition on the Spanish side, a railway route will have to be constructed from the tunnel entrance, which is planned in nowhere land, to either San Fernando or Algeciras. So they have to plan for another 2 billion Euros – at least. This will not be backed by EU funds, because all EU money will have to go into Ukraine.

Good point … assuming eventually it would link up with a line from Malaga … but there is a map at Ronda train station from the 1920s already projecting it… so a decade from now is very unlikely