By Michael Coy

PALOMARES doesn’t stand out in any way. It’s just a typical Andalucían village beside the sea.

Halfway between the Cabo de Gata and the port of Cartagena, it’s about 230 miles east of Granada. You could drive through it without knowing you’d been there. But on Monday, January 17, 1966, Palomares entered the Cold War in dramatic style.

In the 1960s, the United States and the USSR faced each other as the world’s two – mutually hostile – superpowers. By a strategy known as Chrome Dome, the Americans kept several B52 bombers in the air, ready to strike Moscow, 24 hours a day.

Spain under General Franco tried to keep out of the Cold War (so-called because neither side dared start a ‘hot war’, so devastating was the power of their nuclear weapons), but American money was too tempting, and in return for investment funds, Spain granted the USA the right to build a military air base at Moron, near Sevilla (it’s still operational today).

The nuclear bombers flew from home bases in the USA, and navigated non-stop to Europe. Though they had a phenomenal range, in order to stay airborne for hours over Turkey, they needed to refuel in flight. On that fateful day in 1966, a KC-135 tanker aeroplane full of aviation fuel took off from Moron to rendezvous with a bomber 10,000 feet above the Mediterranean coast of Andalucía. And that’s where, on this particular day, things started to go very wrong.

The two American aircraft collided during refuelling, and both suffered so much damage that they fell from the sky.

All four of the tanker’s crew were killed, and three of the seven men aboard the bomber died. The four thermonuclear bombs, which the B52 was carrying, fell onto the village of Palomares.

Mercifully, atom bombs don’t explode on hitting the ground. They work on a different principle, and have to be detonated by pressing a button.

However, the damage caused by all those tons of metal falling out of the sky was extensive. Three of the devices landed on open ground, and one fell in the sea. They released clouds of deadly plutonium gas. Crops, trees and village streets were contaminated by the radiation, and the American government immediately launched a decontamination programme.

They’d found the three bombs which fell on land, but they had no idea where the fourth might be. Obviously, the first phase of the clean-up focussed on finding that weapon: after all, it might be leaking radiation.

As some clever person once said, the world gets wiser as it gets older. In 1966, people didn’t fully understand the dangers of nuclear fallout. American troops were sent in to search the fields and hedgerows of Palomares without any protective gear.

Another serious mistake that the Americans made was to ‘tamp down’ the radioactive dust far too aggressively. They sprayed so much fresh water onto the land that the natural underground reserves were used up, and sea water seeped in, killing all the local crops.

The USA agreed to skim off Palomares’ topsoil, and take it back to the United States in metal drums. Scientists now think that this operation was bungled. They didn’t collect the most contaminated soil, and the metal drums were not properly accounted for.

Spain has been a relatively poor country since its ‘golden century’ finished in the year 1681. In the 1960s, however, a new source of wealth arrived: tourism.

Suddenly, the young people of Britain, Holland and Germany had disposable income, and planes could fly them to Andalucia, which had beaches, sun, sangria and discotheques. The package holiday was born.

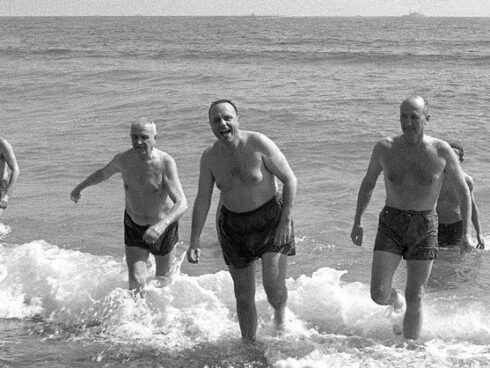

Franco realised that if the world thought of Spain as a nuclear wasteland, the new wealth tap of tourism would be turned off. He told his Minister of Tourism, Manuel Fraga, ‘Do something’! Fraga’s solution was to frolic in the sea for the press, saying, ‘Look, it’s perfectly safe’!

Ironically, where he was paddling is where the fourth bomb was found – but it took them a year to locate it.

Click here to read more Andalucia News from The Olive Press.