A LITTLE-KNOWN independence movement is trying to take root in Spain’s southern province of Granada.

A rabble of rambunctious rebels are seeking to cleave the province from the autonomous community of Andalucia, and escape the so-called yoke of its regional capital, Sevilla.

Leading the charge is author and activist Cesar Giron, who believes Granada could thrive as its own autonomous region.

He points to neighbouring regions to support his argument.

“How is Murcia, which is smaller than Granada, doing? And Logroño, Asturias or Cantabria?”

The region’s history as the former Kingdom of Granada gives the independence movement a historical mandate, he believes.

“It is clear that things have gone badly for us in Andalucia,” Giron adds. “Sevilla has taken everything and left nothing for us.”

While the movement currently appears to have remarkably little public support, it can take heart and inspiration from events further north.

A recent vote in the province of Leon favouring autonomy from Castilla y Leon has brought to the spotlight its own far more evolved independence movement.

One that’s haunted the region since the transition to democracy.

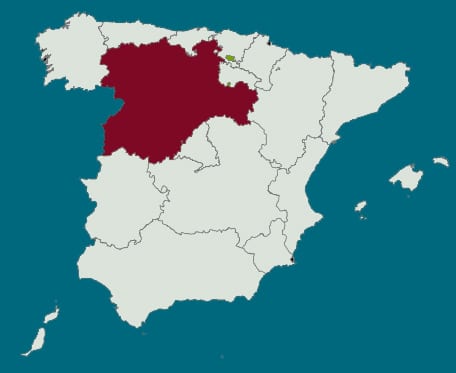

While it remains to be seen whether the Castilla y Leon government will heed the Leonese call for autonomy, activists in the Leonese region — which includes the modern day provinces of Leon, Zamora, and Salamanca — deem it necessary to confront the three main issues facing the area.

They believe that a separation from Castilla well help tackles the related issues of economic decay, depopulation, and what they describe as a deliberate effort to erase Leonese identity.

The historical region of Leon is defined as such through a shared history distinct from that of Old Castille — which includes today’s provinces of Burgos, Soria, Segovia, Avila, Valladolid, and Palencia — as well as through a cultural lineage stretching back to prehistory.

The region also has its own language, Asturleones, which forms a dialect continuum of mutually intelligible varieties spoken across the north of Spain and Portugal.

Its identity was solidified with the rise of the Medieval Kingdom of Leon, which, at its peak in the High Middle Ages, was among the Iberian peninsula’s most powerful — and perhaps most democratic.

An elaborate rural network of alliances between peasants and landowners began to form in Leon in the 7th century, through which small towns maintained a degree of economic independence from the feudal lords, with peasants making collective decisions and settling feuds communally.

The direct democracy of the Consejos, as they were known, was seldom seen in Medieval Europe, and played a key role in the kingdom’s prosperity.

According to Alberto Zamorano, president of the Citizens Collective of the Leonese Region (CCRL) — a group fighting against the ‘cultural erasure and economic and demographic decline’ in historic Leon — an autonomous Leon could help codify the role of direct democracy in Leonese politics.

“Leones autonomy would reinforce this role,” he told the Olive Press, “with specific legislation that would grant them the duties that correspond to them at the legal level.”

Politics, Depopulation, and the rise of Leonesismo

Despite Leon’s inclusion in the 1833 division of Spanish territories, a series of last-minute political decisions urged by the soon-to-be first Deputy Prime Minister Rodolfo Martin Villa during the transition to democracy in the late 1970s led to the merging of Leon and Old Castille into a single autonomous community, largely to the opposition of Leonese.

Polling since has shown high support for Leonese autonomy, with a 2020 survey suggesting 81% of residents of the Leon province supported it.

In 1984, not long after the approval of Castilla y Leon’s statute of autonomy, somewhere between 35,000 and 90,000 protesters took to the streets of Leon under the slogan ‘Leon sin Castilla es una Maravilla’ (Leon without Castilla is beautiful).

Despite the numbers, the protests failed to enshrine Leonese autonomy, though the sentiment behind them never wore off.

In 2024, the lack of economic opportunities in Leon and the corresponding depopulation of rural Spain — which has had a particularly drastic effect on the Leonese region — has influenced the most recent push for autonomy, says CCRL member Hector Alvarez.

As younger generations head to major cities in search of work, the three Leonese provinces have suffered drastic population losses in the past 10 years.

Data from the National Statistics Institute (INE) shows that the population of the Leon province fell by more than 8% between 2012 and 2021, while Zamora’s population fell by nearly 12% in the same period, and Salamanca’s fell by more than 6%.

The region’s ties to Castilla have prevented it from developing an economy sustainable enough to keep its population balance stable, Alvarez says, as only a small portion of the autonomous community’s budget is dedicated to the sparsely populated Leonese provinces.

“We are forgotten,” he says. “We don’t have the capacity to define our own economic policy and we depend on what Valladolid tells us.”

This lack of autonomy has prevented the Leonese provinces from forging their own economic policy specific to their needs.

Tourism in Castilla y Leon, for example, has historically been concentrated in Castilla, mainly in Valladolid, so the autonomous government lacks motivation to develop a large-scale tourism campaign in historic Leon, which could provide jobs and much-needed economic stimulus.

“We can make our own budget, but we don’t have the option to choose a tourism strategy, or industrial strategy,” Alvarez says.

Murky foundations

There’s also the issue of the numerous public ‘foundations’ put together by the Castilla y Leon government, whose purposes are often murky and, despite being funded in part by taxpayer money in Leon, have little to do with Leonese society as most are based in Valladolid.

In some cases, these organisations have political motives, and at times appear to have actively worked to diminish Leonese identity.

“There is a part of the expenditure that’s spent in a very opaque way and is certainly not for the benefit of the people of Leon,” Alvarez says.

One example is the notorious Fundacion Villalar, founded in 2003, whose stated objective is to ‘contribute to the consolidation and development of democratic coexistence and social progress in Castilla y Leon through the promotion, defence, knowledge, and diffusion of values.’

The organisation is named after a 16th-century battle in the Valladolid town of Villalar de los Comuneros, during which a group of bourgeoisie rebels staged an uprising against the rule of Carlos I.

The insurrectionists were crushed, and the battle resulted in the decapitation of the rebel leaders.

The Fundacion Villalar, funded by the Castilla y Leon parliament, uses much of its €750,000 a year to pay for ‘Castilla y Leon Day’ celebrations, a holiday that takes place on April 23 — the date of the battle.

However, the CCRL as well as the Leonese People’s Union — the primary Leonese regionalist political party — have accused the organisation of a campaign to erase Leonese identity.

A series of children’s comics released in 2011 by the Fundacion Villalar and distributed to public school libraries called ‘History of Castilla y Leon in Comics,’ has been criticised for its historical inaccuracy and apparent ignorance of a Leonese history distinct from that of Castilla.

The comics avoid mentions of a Leonese language and imply that a unified Castilla y Leon has existed since prehistoric times.

“They have persecuted any trace of the Leonese past that united the provinces of Leon, Zamora and Salamanca,” Zamorano says.

“This cannot continue like this, and with the autonomous community we would recover the identity and traditions that have been stolen from us.”

The success of the independence movement is still up in the air. The ball is in the court of the junta of Castilla y Leon, who have historically brushed leonesismo aside.

But were Leonese to be granted their wish, it might be the first in a spate of independence dominoes to fall within Spain’s larger autonomous regions.