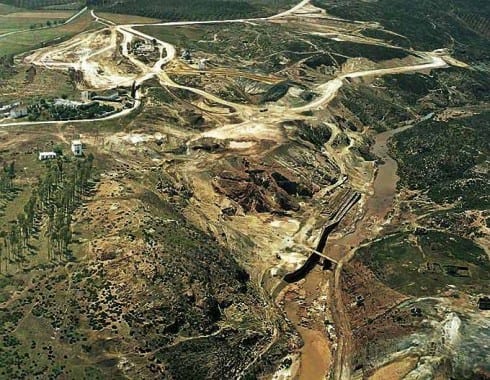

In the early morning of April 25th, 1998, near the Sevillan town of Aznalcollar, a wastewater holding pond at the Los Frailes mine blew a 50-metre-wide breach, sending some six million cubic metres of toxic mud and water rushing into the Agrio River.

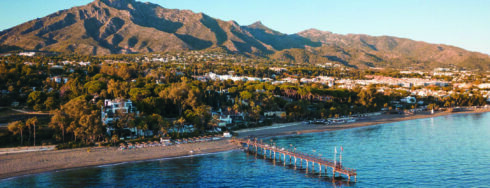

The mine, operated by Swedish company Boliden, was situated not far from the Guadalquivir swamps that form the unique wetland ecosystem of the Doñana National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and known for housing one of Europe’s largest migratory bird populations.

The toxic wastewater — containing traces of lead, cadmium, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, zinc and selenium, among others — flowed from the Agrio to the Guadiamar River, which feeds the Guadalquivir estuary and the wetlands of Doñana.

The result was devastating, with an estimated €240million lost in damages to local agriculture.

The sludge sent pH levels in the wetlands skyrocketing, producing some 29,680kg of dead fish and 218kg of dead crabs in the Guadiamar River.

The incident has become known as the worst ecological disaster in Spain and among Europe’s most catastrophic.

The Junta brought a legal case against Boliden after the spill, though proceedings were dismissed in 2002.

After the company repeated appeals, in 2012 the Supreme Court reopened the case against the company, which remains ongoing.

Prosecutors are seeking €89 million, the amount spent on cleanup efforts during the disaster’s aftermath.

Boliden has always denied responsibility, instead emphasising its cooperation in cleanup efforts and blaming the catastrophe on Dragados, the parent corporation of the construction company that built the wastewater holding ponds.

Now, the mine is set to reopen under new ownership, despite heavy criticism by local ecologists.

According to an April 2024 report from El Pais, the mine will likely reopen in 2025, under management by the Los Frailes Mining Group — which includes the Mexican mining giant Grupo Mexico — after final government approval and the resolution of remaining legal cases.

The reopening project involves a €316 million investment and is expected to generate some 2,000 jobs in the region, reports El Pais.

Plans for the mine anticipate 45 million tonnes of copper, zinc, and lead over the next 17 years.

However, the project’s been widely criticised by activists and ecologists for what they say is an incomplete assessment of how the mine’s wastewater will affect the surrounding ecosystem.

There is particular concern for the state of the highly biodiverse Guadalquivir Estuary, which houses dozens of species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles and invertebrates, including flamingoes, spoonbills, osprey, red foxes, eels, otters, anchovies, whip snakes and shrimp.

The activists argue that the quantities of wastewater from the mine — which can include traces of heavy metals like arsenic, copper, cadmium, mercury and lead — will be too high and too concentrated for the estuary to sustain, likely causing chemicals to collect at the bottom and harm wildlife.

On April 25th, 2024 — exactly 26 years after the disaster — a coalition of activists from Greenpeace, Ecologists in Actions, and some 50 other groups staged a rally in Sevilla to demand that the Junta put a stop to the plans.

“We demand that the Andalusian Government not grant the Unified Environmental Authorization to this project that will poison the river,” said Luis Reina of Greenpeace during the rally.

“We should have learned. You can play Russian Roulette.”

Ecologists in Action points out in its manifesto that Grupo Mexico — a member of Los Frailes Mining Group — was responsible for a catastrophic mining disaster in Mexico’s Sonora River in 2014, during which some 40 million litres of toxic chemical spilled into the surrounding ecosystem.

There’s additional concern that renewed mining activity may present a risk to the local agriculture and fishing industry, with Sevilla being the country? primary rice producer, and the shrimp caught in the area have high culinary value.

“The discharges can put the rice and fishing sector at risk, which is why we do not understand why authorization has been granted by the Ministry of Agriculture, which is supposed to look after their interests,” said Luis Berraquero, also of Greenpeace.

READ MORE: Toxic spill bill: Junta to sue Boliden for €90m over 1988 contamination of Doñana