THE tragedy of the pigeon is a story of humankind’s careless relationship with another species — how a once peaceful, symbiotic connection turned to one of neglect and suffering.

The rock dove, known scientifically as Columba livia, is perhaps the most recognisable bird on planet Earth.

Its slate-grey wings and gyrating head movements can be seen across six continents, equally comfortable in dense urban jungles as windswept sea cliffs or even the Sahara desert.

But despite a complex relationship with humans that’s nearly as old as civilization itself, the rock dove (or pigeon — the terms are used somewhat interchangeably), has found itself deemed a pest and a public health hazard, left to interbreed for centuries with its domesticated cousins, causing feral populations to explode past the point of sustainability.

Winged rats

Though the population of the pure wild rock dove is decreasing worldwide, numbers of feral birds remain in some regions unsustainably high, largely due to abundant food sources in human habitats.

In most urban areas, wild rock doves and feral pigeon populations have interbred for so long that they’ve become largely indistinguishable.

Estimates have put the global population of rock doves at 260 million and the European population as high as 45.2 million.

But in Spanish cities, these numbers have recently reached uncomfortable heights.

Healthy pigeon density in cities is about 300-400 birds per square kilometre depending on the city, past which point they can negatively affect local vegetation and architecture.

And beyond the threats they pose to the human world, pigeons living in urban jungles often suffer indirectly from human activities.

If you’ve ever seen a city bird limping along with a mutilated foot or grotesquely scarred toes, chances are the injury was a result of the bird getting caught in human hairs or fibres from pollution.

Barcelona, for example, has far surpassed its upper limit for healthy pigeon density, with 85,000 birds counted in the latest census.

To combat exploding numbers, city officials have deployed falcons, hoping the birds of prey will send the pigeons scattering.

The falcon ploy comes after a failed attempt to sterilise the population via hiding contraceptives in their food.

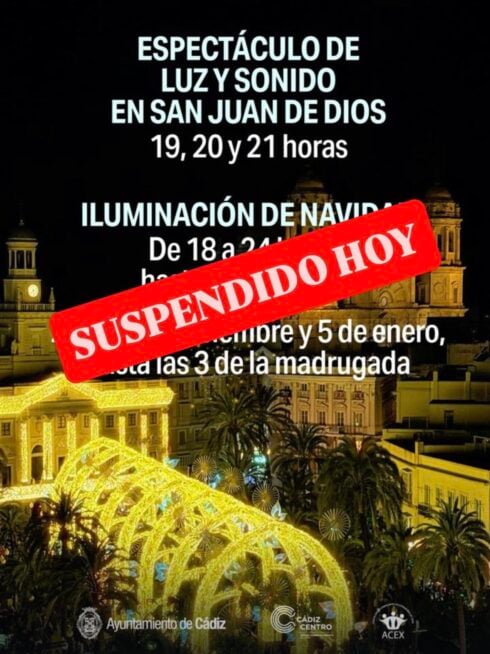

And in Cadiz in 2018, officials had to relocate 5,000 pigeons to a remote corner of the countryside hundreds of miles away after the bold birds began to threaten local tourism, stealing food right from tourists’ hands.

How did we get here?

Pigeons have a long relationship with humans, likely first domesticated by the Mesopotamians and Ancient Egyptians.

They then spread throughout Europe and Eurasia via the Greek Empire, used for both meat and communication.

Pigeons have a highly developed sense of orientation and strong homing instincts, making them ideal for delivering messages across long distances.

They’re also highly intelligent — with some individuals having passed the mirror test after training, indicating primitive self awareness — and some studies have shown that the birds may even dream.

After the Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the Early Middle Ages, the Muslims kingdoms that flourished heavily utilised the birds, relying on them for private and official communication, including on the battlefield.

In the Medieval Kingdom of Aragon, the importance of the pigeon in economics and culture is well documented, with control of feudal dovecotes signifying power and numerous accounts of pigeon taxes and regulations regarding pigeon breeding and hunting.

In Christian symbolism, the dove represents purity, with the Holy Spirit descending upon Jesus after his baptism in the form of the bird.

Pigeons mate for life, and are thus also known to represent loyalty and honesty in European art.

Although domestic breeding began to decline in the 20th century, so called “war pigeons” saw their glory days during the First World War.

Trained to carry messages across hostile fronts, these birds were crucial in war efforts, and in some cases saved thousands of lives.

One war pigeon, named Cher Ami (“dear friend” in French), saved an entire battalion of American troops in 1918, when hundreds of men were trapped behind German lines with no way of communicating with reinforcements except via carrier pigeon.

The fearless bird was shot in the chest and had nearly lost a leg but still managed to deliver the message, saving the soldiers’ lives.

Since then, use of homing pigeons for communication purposes has — for obvious reasons — declined, although domestic pigeons are still bred in some regions for food and racing.

But after centuries of domestication and careless rearing practices, the once prized domestic pigeon has become largely feral.

Homing and racing pigeons became lost en route to their destinations, while landowners abandoned their dovecotes, leaving the birds inside to fend for themselves.

Even today it’s not unheard of to find racing pigeons incorporated into feral urban flocks often far from home, identifiable by bands around their legs.

The result is the bird’s total colonisation of the Earth’s urban areas and the decimation of their wild counterparts due to interbreeding.

It’s thought that only a handful of isolated wild populations still exist, with some orinithologists fearing that true wild rock doves may in fact be extinct.

READ MORE

- Authorities track down pigeon nests in Gibraltar on fears they could spread bird flu to humans

- Resident in Spain faces HUGE fine for feeding pigeons in the street

Click here to read more News from The Olive Press.