Although Spain treats men and women equally by law, and the government has worked hard to educate the entire population about equality, many women still report sexist behaviour and ‘machista’ attitudes.

Some of the most outmoded attitudes hark back to the Franco era of National Catholicism when, in 1939, the dictator removed any powers women had gained. Females were forced to be mothers and housewives, with no legal right to work, own property, or get divorced. They could go to prison for adultery, although straying husbands weren’t punished.

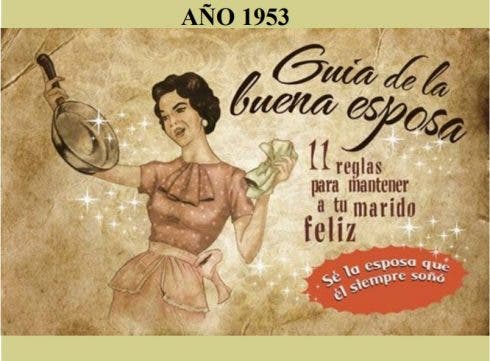

A 1953 guide showed women how to be a good wife, including ensuring that the house was spotless, the children tidy, and dinner on the table. Women were told not to bother their husband with “trivial” chatter. It was a patriarchal society, with women treated as chattels.

Progress has been made

Ever since Franco died in 1975, women’s groups and female politicians have worked to rid the country of a ‘machista’ culture and secure equal rights.

Feminists made rapid progress after the dictator’s death and as Spain developed as a democracy, women’s rights started to match those of other European countries.

The husband’s permission rule was abolished in 1975, the adultery law went in 1978, and divorce was legalised in 1981.

In 1987, the Spanish Supreme Court agreed that a rape victim didn’t have to prove they had fought the man back

In 2004, the government introduced what is known as the “Integrated Law”, which funded the Government Delegation of Violence Against Women. And, in 2017, a State Pact was formed against gender violence.

Carmen Quintanilla, vice president of AFAMMER, which works for women in rural areas explained: “Spain is a pioneer and benchmark country in terms of laws that ensure equality, compared to other countries in Europe and worldwide. Until the elaboration of the 2017 State Pact, never before had a government been so committed to the eradication of gender violence.”

Quintanilla points out that, in May 2019, Spanish Congress had the most female members in its history – 166, taking 47.4% of seats. This made the Spanish parliament the EU leader in gender parity.

In the Cabinet, that number is even higher, with women taking the majority of ministerial roles, including that of Deputy Prime Minister. Not the top job yet though.

However, a backslide occurred in 2019 when the far-right Vox – now Spain’s third largest political party – claimed that the gender violence law favours women and should be replaced with a family violence law. Despite this being controversial, some voters clearly approved.

Vox also has made some questionable statements about women’s working roles.

And when it comes to the workplace itself, the proportion of women in managerial positions remains around a third of that of men with the numbers dropping even further as careers progress.

Spain’s female executives earn 15.1 percent less than their male counterparts, although this is just below the EU average salary gap of 16 percent according to the latest EU data from 2017.

Quintanilla says: “On average, Spanish women earn €5,977 less per year than men and occupy more than 70% of part-time contracts. Of these women, 46% affirm they are part-time because they care for dependents or cannot afford childcare services.”

Does Spain have a high femicide rate?

The Spanish government site for domestic violence (DV) and equality provides annual statistics about and femicide. At the end of 2021, Spain became the first European country to start recording all femicides, even in cases where the aggressor didn’t know the victim.

In 2022, 44 women were killed and nine of the male perpetrators had previously been denounced for domestic violence (DV). This compares to 47 in 2020 and 55 in 2019. Harking back a decade, Spain had 73 deaths of women at the hands of male partners or ex-partners in 2003 and 72 in 2004, so rates have at least decreased.

According to statistics, Spain has 2.3% of femicides for 100,000 of population, which is low compared to many other countries – especially Ethiopia and Latin America. Many other European countries exceed Spain for femicide rates.

The UK isn’t exemplary either. Figures showed a 6% rise in DV for the year ending March 2021, which included the Coronavirus lockdown.

The ‘machista’ issue

Studies show that DV is more likely to occur where “attitudes and behaviours reinforce men’s dominant position over women” – so machismo clearly isn’t a good thing.

While living in rural Andalucia, the author has experienced the problem at first-hand. This includes receiving comments that she should be at home cooking and cleaning, the suggestion that “women don’t raise their voices to men” and being sworn at for not washing dishes properly. She has found a ‘Man Club’ culture, where men gather in groups, drinking, and expect women to remain at home doing chores.

Teen boys have also been witnessed copying toxic male attitudes, saying that wives and mothers should do all the housework because it’s “their job”.

Vanessa, a 30-something Spanish bar proprietor in the rural Alpujarra, said: “I’m not sure the younger men are different. It depends on how open-minded individuals are. It’s easier to use a washing machine than a PlayStation.”

Worryingly, a recent Ariel / Ipsos study suggests that just 57% of 20–35-year-old respondents share household chores, while 42% of older women think they perform certain household chores better than men, compared to 33% of young women.

Carmen Quintanilla says: “We still have to move forward – we are taking steps and breaking mentalities, especially within our youth.” She worked to introduce a National Day of Reconciliation and Co-responsibility in Spain, starting in 2018, to encourage young people to share household tasks.

Is the law applied fairly?

While not using household appliances is one thing, bullying women – and children – is another. What happens in parental disputes? Some Olive Press readers believe that the father is sometimes unfairly favoured.

While Quintanilla says the child is treated as a “protected asset”, a British reader reported problems. She says: “My son and I are in hiding after spending a year in women’s refuges. When I fled my ex, we went straight to the police. However, they didn’t provide a translator for the initial statement and wrote it inaccurately, failing to include the rapes, violence towards me and our three-year-old son, the drug dealing and my ex using our child’s bedroom as a drug lab. They arrested him, locked him up for one night, didn’t search the house and didn’t get a translated statement. As a result, the domestic violence case was thrown out of court because the statements didn’t match.”

She adds: “We are now at risk because the ex is demanding unsupervised visitation and the restraining order was dropped with the violence case. The courts have a backlog, and it feels like the case was rushed through, details were completely ignored, and now the ex has a stronger case for custody. I have maximum respect for the refuge staff but little faith in the police and courts.”

Anne, a British grandmother, is also critical. She says: “We proactively involved the local Social Services when we discovered that my daughter’s baby father was being aggressive with my grandson, who was aged six. Despite this man being denied contact with his previous daughter for similar reasons, they continued to grant access. We felt like there was collusion because he was from a known Spanish family, while we were foreign women.”

Anne concludes: “Although the father’s access ended when the daughter testified against him, Social Services removed my grandson to an establishment in the nearest city and put his older sister back with her father – this was after they made an unscheduled visit and found some plates lying around and us coughing with winter colds. I felt like it was the Spanish Inquisition; that they were judging us as single women from a different culture, and we didn’t measure up.”

READ ALSO:

- What Women’s Day means to three generations of strong Spanish women

- OPINION: How Spain is outpacing the UK when it comes to women in politics