THE earthquake in Morocco last week has so far killed more than 2,300 people in what is the country’s worst natural disaster for decades.

The quake rocked the north African country overnight on Friday, taking thousands of citizens by surprise, with many unprepared buildings simply collapsing.

The event has raised alarms in Spain following a spate of seismic events in Granada in recent months.

It has also highlighted the concept of the so-called ‘geological kiss’, a term used to describe how the continents of Europe and Africa are moving closer and closer together.

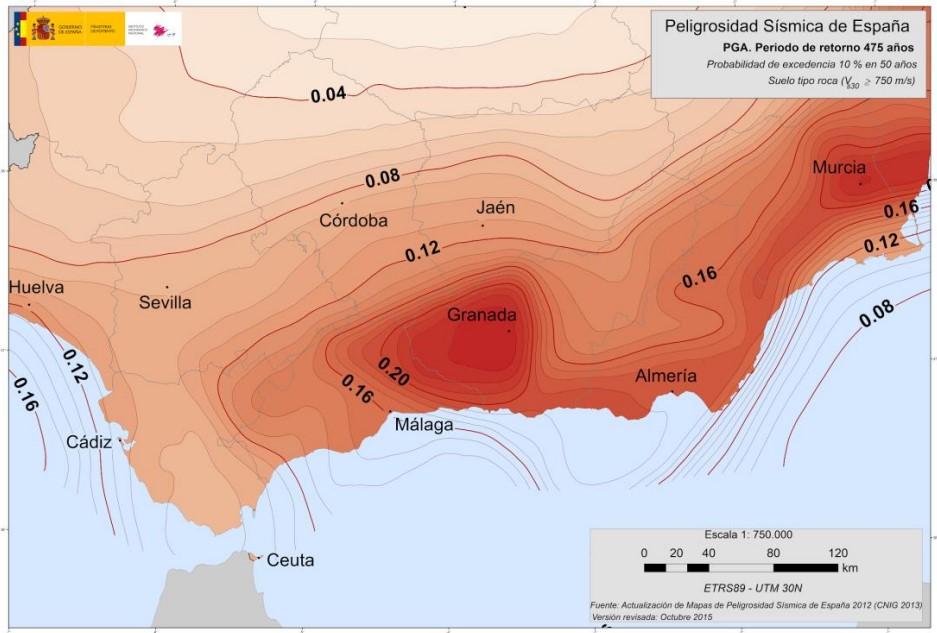

The phenomenon has been behind recent quakes in Granada and places more than 14 million people in Spain in areas of high or very high seismic risk, reports Andalucia Informacion.

Jesús Galindo Zaldívar, professor at the University of Granada, told Spanish newspaper El Pais that “the African and Eurasian plates approach each other each year by between four and five millimeters.”

According to a report from the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME) by researchers Julián García-Mayordomo and Raúl Pérez López, from December 2020 to January of this year, more than 430 earthquakes with magnitudes between 3 and 4.5 were recorded in the Atarfe area, next to Granada.

Experts say seismic activity in the region is not a new phenomenon, but part of a ‘constant tectonic stress field’ that could trigger future earthquakes in the Iberian Peninsula.

According to Pérez López the “hot zone” stretches from Huelva to Alicante and includes the Pyrenees and part of Galicia, where the risk of an earthquakes is high.

Speaking in 2021, he explained that it is better to have lots of smaller quakes than one big one, and that it was unlikely to see a quake higher than a magnitude of six.

However, it is currently practically impossible to predict when an earthquake will strike and how big it will be.

In the start of 2021, earthquakes in Granada never surpassed 4.5 on the Richter scale but were still able to shake buildings and collapse ceilings.

It comes after a new tectonic fault was discovered by Spanish scientists in 2018.

Geologists unearthed the fault under the westernmost part of the Alboran Sea following an expedition led by the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and the University of Granada.

The findings were published in scientific research journal Tectonic, warning of potential new geological risks in the area around the Alboran Sea.

The Andalucian scientists believe the new fault zone was the cause of a 2004 quake which killed more than 600 people with a magnitude of more than 6.3 in Al Hoceima, north Morocco.

They also believe it was behind strong seismic activity between 1993-4.

According to the study, the fault line could still trigger relatively high magnitude earthquakes such as the 6.3 earthquake which rocked Melilla and several areas of Andalucia on January 25, 2016.

It also warned that the growth of recently formed faults could cause higher magnitude earthquakes in the ‘Gibraltar arch’, between Iberia and Africa, as well as the Campo de Dalias region in Almeria.

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.