THE Civil War might have been over, but in August 1948, 75 years ago this week, the 200 residents of a tiny white village became what could be described as casualties of war.

When right wing dictator Franco’s forces won in 1939 they still had to contend with uprisings – and they did so with great ferocity.

Frigiliana, perched in the mountains above Nerja on Andalucia’s Costa del Sol, was declared Republican in 1936, only to fall to the fascists the following year.

Anyone suspected of supporting the left wing movement came into the sights of Franco’s forces, who took bloody revenge.

The village and its near neighbour El Acebuchal – today in the heart of the soaring Sierra Tejeda natural park – found themselves on the frontline of a guerilla war and were caught in the crossfire.

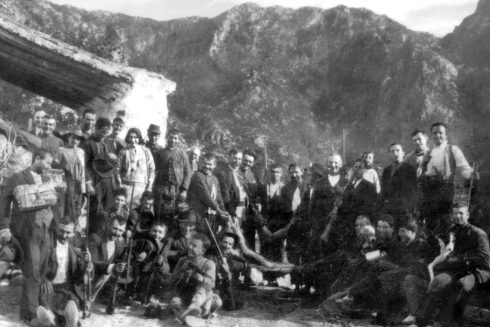

Following the end of the Civil War, left wing sympathisers had taken to the mountains and formed a guerilla force known as the ‘Maquis’ to fight the fascist victors – a movement that was not to be finally crushed until 1952 when the last fighter – Antonio Sanchez Martin – was killed by Guardia Civil forces in front of his two young daughters.

His body was then draped across a mule and led through the streets of Frigiliana as a warning to the silent villagers.

Frigiliana paid a heavy price in terms of blood with communist sympathisers shot on sight, while El Acebuchal basically ceased to exist.

Suspected of helping the rebel fighters with food and refuge, the Guardia Civil ordered the villagers to leave.

In truth, the villagers were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Politically they were a mixed bunch, some had actually even fought on Franco’s side during the Civil War.

But to the Guardia this did not matter. Everyone had to go.

They fled, leaving behind all their possessions and the homes that most had lived in all their lives.

Many moved into neighbouring villages taking refuge with relatives and started new lives. Technically they were allowed to return to their old homes during daylight hours, but they could not stay overnight – not much good when they were often living several hours walk away.

Gradually, El Acebuchal fell into ruins, deserted with just the inn remaining open to service the needs of muleters on the old mountain route to Granada.

But when they stopped passing, the final death knell of the hamlet was rung and the inn closed.

El Acebuchal crumbled until little more than mounds of rubble and a few standing walls were left, and it became known to locals as the ‘lost village’.

But it lived on in the memories of the former residents until decades later in 1998 one couple decided to do something about it.

Virtudes Sanchez and Antonio García ‘El Zumbo’ whose parents had been expelled, realised that the burgeoning ‘rural tourism’ sector meant the village could be brought back to life.

They started with three plots that belonged to relatives and started to rebuild the village stone by stone, soon acquiring another 11 of the former homes. They worked tirelessly with no electricity or running water for years to get things back into order.

Finally their work was done in 2003 and the lost village was once more on the map.

Other former residents and their descendants soon joined the effort, and today, incredibly, 33 homes have been rebuilt.

Few people live there permanently, with most of the homes rented to tourists and today, where farmers, charcoal burners and muleteers used to live, foreigners relax on holiday among the stunning natural tranquillity.

As visitors hike in the hills, bask in the sun and enjoy the mountain air, it is difficult to imagine the violence and terror that once caused El Acebuchal to become lost.

But now, after 75 years, it has finally been found again.

All photos credited to https://www.elacebuchal.com/