By Carlos Pranger

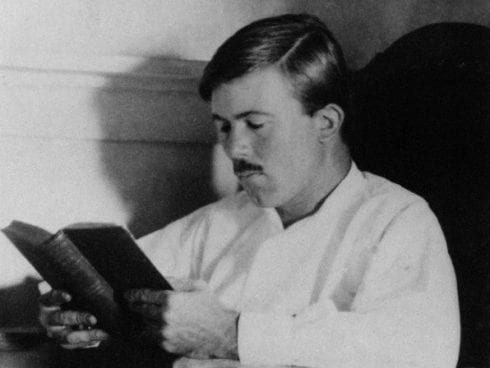

WHEN the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Gerald Brenan was living with his wife Gamel Woolsey in Churriana, a village west of Málaga.

At first they decided to stay on, but the situation became so dangerous they finally returned to England. Hurt, disheartened and surprised by the cruelty and hatred displayed by the Spanish people, Brenan wanted to understand why the civil war had started. After intense research, he produced The Spanish Labyrinth, a key work of analysis on the causes of the civil war.

On his return to Spain 10 years after the war ended, Brenan travelled with his wife Gamel through the south of Spain up to Madrid and kept a diary on his impressions of the country under General Franco’s dictatorship. Drawing on his knowledge of Spanish life and customs he wrote The Face of Spain, a book which gives an accurate image of a country still under reconstruction after the war and governed by a dictator.

Spain was in a sad and depressing state, stricken by severe drought, famine and poverty. Its leading party the National Movement, instead of guiding the reconstruction, was a nest of corruption supported by a large black market. Gerald and Gamel visited Granada, one of the cities most punished during and after the civil war. The atmosphere was strange.

Brenan knew the city quite well, as he had been an assiduous visitor while he was living in the village of Yegen. Granada was a small provincial town, austere and conventional. Now it was more than austere, it was sad. People’s faces were gloomy, the streets and shops empty, and the previously lively quarters seemed silenced. Brenan describes the atmosphere as being full of resentment, a suppressed anger and tension enclosed the entire city. Workers looked suspicious and spoke with bitterness. It was much worse than other places they had visited.

Gerald and Gamel walked up to the former Jewish quarter, the Albaicin, and from there to the gipsy quarter, the Sacromonte. Looking down over the city, Gerald sensed the reason for Granada’s sadness: “This is a city that has killed its poet.” They started to look for Lorca’s grave to lay a wreath of flowers on it. A symbolic homage to one of Spain’s best poets.

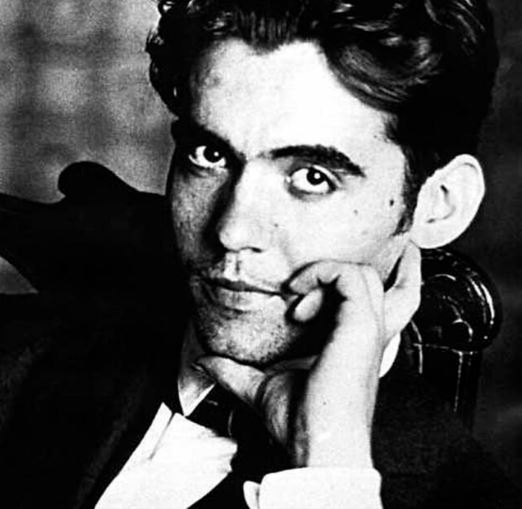

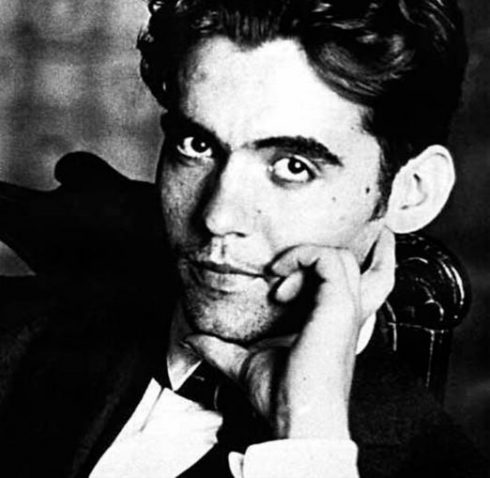

Gerald had actually met Lorca in Granada in the 1920s when the poet was starting to gain recognition for his poems and plays. They met at the house of a mutual friend, a local aristocrat called Rodríguez Acosta. Gerald Brenan in those days was not a writer, only an eccentric retired soldier living in La Alpujarra. He was very taken by Lorca’s neat way of dressing and fine manner. They got on well together but this did not turn into real friendship as Lorca left soon afterwards to live in Madrid. Gerald admired Lorca as a cultivated man who had an understanding of popular culture such as flamenco, plays and coplas, or folk-poetry.

In 1936, Accion Catolica, the clericals syndicate, hunted down all liberals and freemasons of the city and anybody connected to the left was persecuted. Fascist party Falange also inflicted against those on the left a hidden oppression. They were organized in secret cells, and drew up lists of the people to be killed. Those on the list were taken at night by the Black Squads and never seen again.

Lorca had arrived at Granada a couple of days before the military rising broke out. He had a great number of enemies amongst the conservatives, as he was a left wing intellectual, a poet and homosexual, and had criticized the narrow, conventional minds of Granada’s bourgeoisie, who he called “the worst in Spain.” Also, he was the brother in law of Montesinos, the socialist mayor of Granada, and a close friend of Fernando de los Ríos, the leading socialist intellectual of the city. Knowing this, Lorca hid in the house of his friend Luis Rosales, whose brother was a leading Falangist. During his friend’s absence, a group of gunmen took him away and he was never seen again.

Gerald and Gamel visited the city’s cemetery. They walked up Avenida del Generalife. Foreign guests staying at the Washington Irving hotel remember this road. Every night they heard lorries packed with prisoners change gears on the slope, after a while they heard shots and then silence. Obtaining information was not an easy task as the Civil War had left a great deal of fear and suspicion behind it. At the cemetery, after making many enquiries and seeing a small enclosure with thousands of skeletons, they found out Lorca’s body was not there. But two local gravediggers put them on the right trail; Lorca was buried in the ravine or barranco of Viznar. Gerald knew many people in the city and he went to see them to confirm the gravedigger’s information. Lorca and Viznar were two forbidden names – something to keep quiet about – but it was a secret known to everyone.

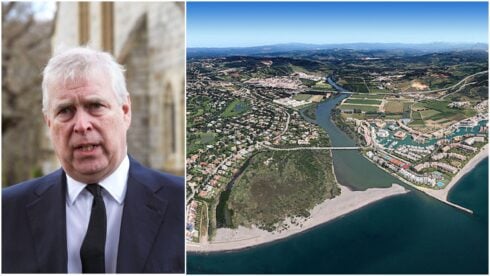

Gerald and Gamel took a taxi up to Viznar, a small pueblo lying on a hillside a few miles from Granada. Its ravine was tragically known to be a Falangist burial ground, one of the many scattered all over Spain. The taxi driver was a Nationalist, probably a spy watching their activities. In Viznar, a local woman guided them to the well-known barranco and, as they went, she described the horrors that happened there. When they reached the place, they took off their hats and Gerald threw a blue grape hyacinth into the wind flowing through the barranco.

For 12 years, Lorca’s name and books were kept under a strict censorship. But this changed because of international pressure. The poet had become a symbol and his death was a bad advertisement for Franco’s regime in its task of trying to open up internationally. The two leading Nationalist syndicates, the Falange and the Clericals, blamed each other for the crime.

Gerald Brenan can be considered a pioneer, in the search for Lorca’s burial place and the first to throw light on the poet’s death. A few years later inspired by Gerald Brenan, Ian Gibson started a deeper investigation, which has produced two wonderful books, The Death of Lorca and Federico García Lorca: a Life, two masterpieces of contemporary writing and research.

Click here to read more Olive Press Travel News from The Olive Press.