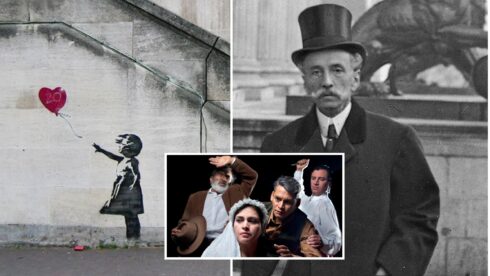

PICASSO was living in Paris when German bombs rained down on the Basque city of Guernica.

Stark black and white photographs plastered over the front pages of L’Humanité and other French newspapers were the first visual representations he saw of the bloodshed and devastation.

Those images became his inspiration for one of the world’s most iconic paintings, a universal howl against the atrocities of war which attracts millions of visitors to its Madrid home at the Reina Sofia Museum last year.

Picasso’s choice to paint it in monochrome has been cited as a deliberate effort to represent a photographic record of the genocide, despite its avant garde style.

Picasso had originally been commissioned to paint a mural for the 1937 Paris Exhibition. But he abandoned his original idea in favour of the mural-sized painting on discovering what had happened in his homeland.

Its unveiling that summer garnered little interest. Few people fully understood it as Picasso resolutely refused to discuss its symbolism.

In fact, the official German guidebook to the exhibition advised against visiting Picasso’s ‘hodgepodge of body parts that any four-year-old could have painted’.

Later it would tour the world and become the focus of countless scholarly works analysing

its striking motifs.

The most haunting symbols are the bull and the gored horse. But look beyond those and you can learn about the atrocities of the Spanish civil war and peer into the mind of the Malagueno artist.

Guernica scholar Anthony Blunt separates the painting’s central pyramid into two groups: the first containing the bull, horse and bird, the second with a dead soldier and various women in different manifestations of grief.

The overwhelming female presence is representational of the ratio of men to women in the town at the time of the bombing. Most men were away fighting.

Art historian Patricia Failing says: “The bull and the horse are important characters in Spanish culture. Picasso himself certainly used these characters to play many different roles over time. This has made the task of interpreting the specific meaning of the bull and the horse very tough. Their relationship is a kind of ballet that was conceived in a variety of ways throughout Picasso’s career.”

Picasso used the minotaur motif throughout his pieces, and it’s said to represent his alter ego.

However, he himself said that the bull in Guernica signifies brutality and darkness, and that the speared ‘workhorse’ represents the people of Guernica.

Under the horse lies a dismembered soldier. On his palm is a stigma which symbolises martyrdom. In his other hand he clutches a broken sword out of which a very faint flower grows – often interpreted as a symbol of hope.

Grisly fragmented motifs remind us of a tragic moment in Spain’s history, but the canvas itself has a story of its own to tell.

Beginning its life at the Spanish Pavilion in Paris, it subsequently toured Scandinavia and was exhibited in Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

It was then sent to the US to help raise money for Spanish refugees and housed in New York’s Museum of Modern Art before travelling around the country and then to South America.

It was under Picasso’s express wishes that it was not delivered to Spain until the country became a Republic.

It arrived here, weathered and worn, in 1981 – six years after Franco’s death – where it now rests, a symbol of peace that will outlive us all.

READ MORE:

- Childhood inspiration: On the trail of the young Pablo Picasso through Spain

- Stepping inside Picasso’s childhood home in Malaga on Spain’s Costa del Sol

Click here to read more La Cultura News from The Olive Press.