MALAGA’S hugely famous local dry wine enjoyed a 200-year boom until the early 20th century when it faded into obscurity. When winemaker Victoria Ordoñez began researching its history, she embarked on a mission to find and recover the old vineyards and start producing it again.

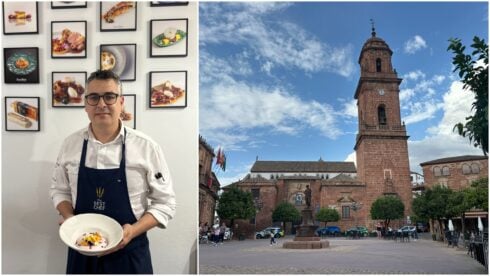

Seven years on, Victoria Ordoñez Winery’s Malaga wines feature on the lists of Michelin starred restaurants around the world. Now, she’s keen to raise awareness closer to home where few know about this illustrious period in Malaga’s wine making past – or that so many fine dry wines are produced across the region today (“they are rarely offered”).

More than anything, she’d like to see Malaga wine given the respect it deserves: “I want to bring it back to the position it held 150 years ago,” she says, “when it was known everywhere, and trade was at its peak.”

Research

Ordoñez was destined to work in wine: her father, Jose Maria Ordoñez, was a leading distributor of fine wines in Malaga, and her brother, Javier, still is. Although she studied medicine and became a doctor (working in biomedical research), meeting and working part-time alongside Austrian oenologist superstar Alois Kracher in Malaga’s vineyards, drew her back in.

When he died in 2007, she decided to focus on wine production full-time. Kracher was one of the top names in sweet wine, but her passion was fired by the idea of recovering the almost forgotten traditional tipple.

Poring over ancient books, documents and maps she read that Malaga wine was so highly prized it was the only type of Spanish wine included at the first wine auction at Christies in London, in 1779.

“Malaga wine was comparable in importance to Burgundy and Madeira; at one time it was the most expensive in Europe. The UK was one of the best markets, and it was also exported all over the world to South America, China, North America (it was stocked in the cellars of all the American presidents) and Russia where it was tax-free because it was the favourite of Catherine the Great.”

Ordoñez discovered the famous – and most definitely dry – Malaga wines the English called ‘mountain wine’ and Malaguenos simply called ‘Malaga’ had been made from Pedro Ximenez grapes (that most of us now by default associated with sweet sherry), and that the most important growing area had been the high, cool slopes of Monte de Malaga.

Malaga boasted 113,000 hectares of vineyards during the glory days, which is almost twice the vineyard density of La Rioja today. In the 19th century, 900 lagares (wineries) were registered in Montes de Malaga alone to meet the huge demand.

When Phylloxera – the vine disease spread by insects – reached Malaga in 1878, the density of vineyards made the effects especially devastating, and the Pedro Ximenez was almost entirely wiped out.

Efforts were made to replace it, but by the time there was success, the economy had collapsed, and the reputation of Malaga wines had declined. “In the end,” she says, “people had started replanting Moscatel instead because it offered three commercial options: it could be used for wine, and for raisins and grapes as well”.

Finding the grapes

So to resurrect the tradition, Ordoñez had to first locate the Pedro Ximenez grapevines. An old book provided clues: “Cristobal Medina Conde y Herrera wrote about the best areas of production for wine and raisins in the 18th century book Conversaciones Historicas Malaguenas. He described the locations very well.”

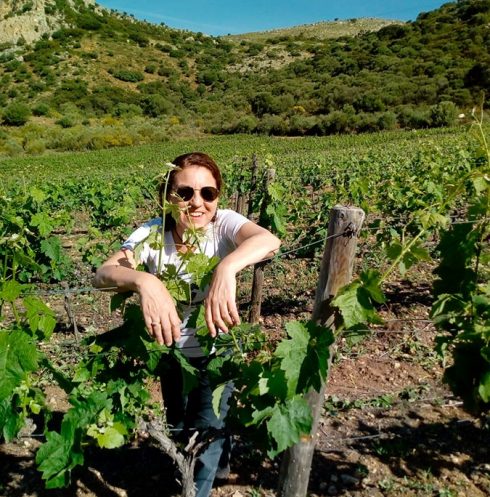

Even so, they proved tricky to find. “The remains of these old vineyards were completely hidden, high in the forests in Montes de Malaga, and each plot was very small. I drove kilometres along bumpy tracks looking for them, stopping to ask people if they recognised the name of old wineries.”

After many months, about a dozen plots were selected, all at altitudes of 800-1000 metres, ideal in the heat of Southern Spain. The youngest vines are 50 years old, but most are between 90 and 100 years old, and there are even a few rare ‘pre-phylloxera’ vines in vineyards that feature on records dating back to 1787. “The land, the climate and the soil combine to create a fantastic, unique terroir.”

Adding Moscatel from vineyards at altitudes of 1000 metres in the Sierra Tejeda Natural Park in Axarquia, and a small quantity of high-altitude Cabernet, Petit Verdot, Syrah and Tempranillo to make reds and rose, she opened the Victoria Ordonez & Hijos winery in Malaga (close to the airport) and moved onto the business of producing it in 2015.

Heroic work

This also had its challenges: “The poor soil and the age of the vines, means we have yields of less than 1000 to 2000 kilos per hectare compared to 20,000 per hectare in other regions.” Many of the mountain vineyards are on a gradient of 46-76 % and, “unlike vineyards in other steep regions,” she says, “these aren’t terraced. They’re almost vertical, hard to walk in.”

But the people who tend the vines are experts. The grapes are handpicked, as they have been for centuries and, in many cases, by the same families. The set-up is ecological, and sustainable by choice and necessity: the vines are rain-fed, and it’s labour-intensive and non-mechanised (donkeys are used to carry the crates).

Unsurprisingly, this style of production is officially (and deservedly) known as ‘heroic viticulture’.

The first year, she made a dry white made from Pedro Ximenez with a touch of Moscatel (La Ola del Melillero). The following year, she added another (Voladeros), made entirely from Pedro Ximenez grapes. And, after a 100-year pause, authentic mountain wine was back in production.

Local pride

“Malaga wine is part of our heritage and our identity,” says Ordoñez. “Once I knew there was a hidden treasure here, I had to find it, dig it up and share it. That’s my drive.

“There is no monument to wine in the city, nothing to say that in the neighbourhood of El Perchel alone there were 101 coopers, but the city itself is a monument to our heritage, from the English, German, Dutch and Italian surnames of people who settled here because of the commerce, to the harbour that was enlarged again and again to allow for the wine export. And it was money from the wine trade that allowed the iron industry to develop in Malaga and led to the production of the wrought iron balconies.”

It’s not only a lack of awareness of the past that she finds frustrating: “While the sweet wines are beautiful, almost half the production in Malaga is dry wines – white, red and rose. There’s an absolute lack of knowledge about that.”

More local support is needed for local wines, she says: “I think this is the only place in Spain where it is difficult finding the local wine. It’s usual in Cadiz, for example, to see Cadiz wines at the top of the wine list, followed by Andalucian wines, then those from other regions.

“In these ‘km 0’ days, if the fish has come from the harbour and the tomatoes from the local grower, but the wine has come from 1000 km away, it doesn’t make much sense to me. Local wine is closely related to our culture, history, and climate; it has to do with who we are. It’s normal for anyone coming here with an interest in gastronomy to want to experience that.”

And on a completely practical level, nothing works as well as a local pairing. She recommends trying the elegant Voladeros mountain wine with the traditional mountain fare of Iberian pata negra; La Ola del Melillero with any seafood, but particularly Malaga shrimp; and the silky Cabernet (Camarolos) with a hearty paella de carne.

Of course, the dry sparkling rose, Las Olas Del Melillero, is the perfect accompaniment to Christmas and New Year celebrations, wherever you are.

These Victoria Ordoñez wines, along with Monticara (dry, Moscatel) and Marti-Aguilar (Petit Verdot), are available in good restaurants in the cities of Malaga and Marbella, and more widely from fine wine merchants including Club del Gourmet at El Corte Ingles, as well as the website: www.victoriaordonez.com.

Vineyard and winery visits and tastings are available by arrangement. See the website for details.

READ MORE:

- Salud! What makes Spanish wine so special?

- La Inglesa: The extraordinary love story behind a winery in the heart of Spain’s Andalucia and the Englishwoman that…

- Under the sea: Five wineries in Spain with underwater cellars that you can visit

Click here to read more Olive Press Travel News from The Olive Press.