THE minute hand on Madrid’s Puerta de Sol clock tower nears midnight.

Millions of Spaniards already have a grape in their mouth. Millions of others wait until the first of the 12 clock strikes to start eating.

Some eat the stem of the grape – others eat them peeled, de-pipped or with bitter pips in place. But by midnight nearly everyone in Spain will have gobbled down 12 grapes in the hope it brings them fortune in the New Year.

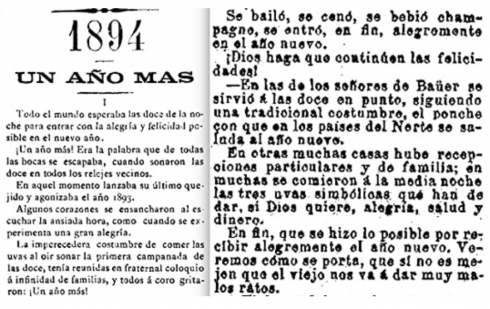

There are as many theories about the origin of this most Spanish tradition as there are ways of eating the 12 uvas de la suerte (‘grapes of luck)’.

The grape-growers of the valley of the Vinalopó river in Alicante province would like to believe they invented the tradition following a bumper crop in 1909.

Their case is a strong one, as 90% of all grapes eaten along with the last 12 clock chimes of the year come from the Vinalopó grape-growing region.

It was them who in the early 1900s pioneered the special technique of wrapping the Aledo grape in paper, which meant grapes could remain on the vine and be harvested well into December.

A fleet of 13,000 workers work tirelessly to wrap more than 200 million paper bags around grape clusters in the villages of Novelda, Monforte del Cid, Aspe, Hondon de la Nieves, La Romana and Agost each year.

It’s the only grape of its kind in Spain that can do such a thing, so it’s a natural conclusion that Vinalopó started the whole thing.

There’s just one problem: there’s absolutely no evidence.

Earliest estimates say the paper-wrapping invention began between 1918 to 1920.

One researcher from Motril in Granada believes this comes 40 years after the tradition actually began among poorer residents in Madrid poking fun at the aristocratic scrooges in charge of the capital.

The year was 1882, and Madrid mayor Jose Abascal y Carredano was fed up with the excessive parties that spilled out into Madrid’s streets around the New Year.

At this time, according to researcher Gabriel Medina Vilchez, the festivities took place on 5th January on the eve of Spain’s traditional Three Kings’ day (Dia de los Reyes Magos).

It was the biggest festival of the year.

Jose Abascal had a cunning plan – a tax of 5 pesetas on anyone in search of a good time on Madrid’s city streets. It was a steep price at the time, aside from being something you could imagine Charles Dickens’ character Scrooge would get behind.

In those days few held parties on New Year’s Eve, except for wealthy aristocrats and people in government who had seen the French bourgeois tradition of eating grapes and consuming Champagne on their privileged travels abroad.

As grapes were cheaper in warmer Spain, this meant the Madrileños denied a good knees-up on January 5th decided to congregate in Madrid’s Puerto de Sol square on December 31 when no tax was in place.

Puerta de Sol then housed Spain’s Ministerio de Gobernación, which ran the country. It was the kilometre 0 of Spain and the central building of the entire nation.

To poke fun at the bitter Spanish bourgeois, people began eating grapes before midnight while wishing one another good luck in the coming year.

The tradition was so popular that it spread all across Spain, including Spanish-speaking countries abroad, and gave some grape-growers in Vinalopó something to rub their hands over.

If you read any origin story of the 12 grapes in Spain, you’ll likely find the 1909 bumper-crop myth front and centre amid accolades of the ‘greatest marketing campaign’ of Spanish history.

Like many traditions however, this one could have started as just a bit of fun before business owners began layering on the mythology.

READ MORE:

- ¡Feliz Navidad! These are the strangest Christmas traditions celebrated in Spain

- Spanish festive traditions: Do you know your Nochebuena from your Nochevieja?

- Snails and thistles: These are the weird and wonderful regional Christmas dishes eaten across Spain