ALICANTE is an unlikely candidate for the original home of Santa Claus – for starters, it hasn’t snowed in the city since 1926.

There are no reindeer in Alicante, not even in the Rio Safari Elche zoo, and few houses on the sunny Costa Blanca even have a chimney.

Some British parents might leave a glass of Spanish sherry out for Santa Claus – but sherry is from Jerez in Andalucia, 600km away from Alicante.

It’s a tenuous link – until you delve into the history books.

Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of Alicante, and if it wasn’t for this historical fact there’s a good chance Santa Claus would never have existed.

So why is Alicante considered the original home of Santa Claus?

Saint Nicholas of Bari

It’s common knowledge Santa Claus is based on the historical figure Saint Nicholas of Bari.

You can trace the history in his name – Santa Claus is an Anglicisation of the Sinterklaas, itself from Sint Nikolaas, the Dutch version of the Latin Sanctus Nicolaus.

Saint Nicholas was a Christian bishop born in 270AD in the modern-day town of Demre on the southern Mediterranean coast of Turkey.

He rose to fame among early Christians for a series of miracles – like the resurrection of three children pickled in brine by an evil butcher during a famine – but in other stories you can clearly see the origin of Santa Claus.

Saint Nicholas’ most famous story was his rescuing of a destitute father from sending his three daughters into prostitution.

Legend says he dropped a sack of gold coins through an opening – a chimney, perhaps – in the fathers’ house which allowed him to pay a dowry for his eldest daughters’ wedding.

He did the same over the following two nights, waiting until sundown to save the father the shame of accepting the money, until on the third night the father caught Saint Nicholas in the act and fell down to offer thanks.

Saint Nicholas became the patron saint of children, and traditions of gift giving are associated with the celebration of his feast day on December 6 each year.

Fewer than 200 years after Saint Nicholas’ death in 343AD, Roman emperor Theodosius II ordered a church built in Demre to allow pilgrims to visit his remains for prayers.

In 1087, Muslim Turks conquered the region and so – fearing desecration – Italian sailors brought Saint Nicholas’ bones to their hometown of Bari in the southern Puglia region, where they remain a major site of pilgrimage until today.

When Santa Claus was Spanish

Spanish conquistadors busy reclaiming the Spanish mainland from Muslim rule knew of Saint Nicholas.

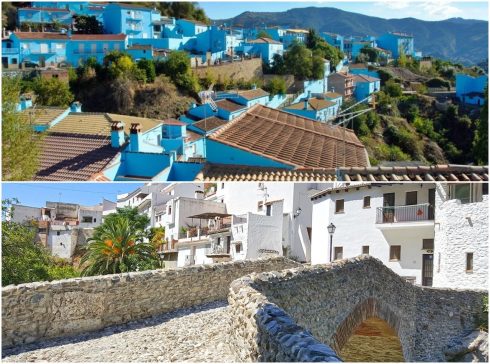

Alicante fell in 1244 to Alfonso X of Castile on December 6 – the feast day of Saint Nicholas – and he ordered a church built on the site of the city’s former mosque.

The Co-cathedral of Saint Nicholas of Bari remains the major religious building in Alicante city, and Saint Nicholas remains the city’s patron saint.

Stories of Saint Nicholas later travelled to the Netherlands when Phillip II of Spain ruled Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily (including Bari), and later the 17 provinces of the Netherlands from 1555.

His name became Sinterklaas in Dutch, and every November until today a fat, white-bearded old man dressed in red-and-white robes sails in on boat from Spain bearing gifts for well-behaved young children.

Because Alicante had Saint Nicholas as its patron saint, the city became associated as the port of departure before arriving in the Netherlands.

But oranges also have a part to play – Sinterklaas traditionally bears sweet oranges and mandarins from Spain upon his arrival in the Netherlands, alongside the Spanish delicacy of marzipan.

The Moors introduced oranges to Spain in the 10th century, but they were bitter.

The first sweet-tasting oranges are the result of a Catholic priest, Father Vicente Monzo Vidal, who set up a commercial farm in 1781 in Carcaixent near Valencia.

Their massive popularity later turned the nearby port of Alicante into Spain’s third-largest as oranges were shipped all over northern Europe, until the city became the de facto home of Sinterklaas for the Dutch.

From Sinterklaas to Santa Claus

Dutch colonialists were the first to lay claim to important areas of North America.

They seized Manhattan – originally calling it New Amsterdam – and Dutch history can be recognised as the cities of Haarlem and Breukelen gave their names to Harlem and Brooklyn, among many others.

Dutch settlers also brought along Sinterklaas traditions which were not then celebrated in the British Isles.

Traditions merged with ones from Germany, like the decorations of evergreen fur trees – Christmas trees.

Legend says that after the war of independence from the British, the newly formed United States sought specifically non-British traditions that would distinguish them from their colonial forebears.

In 1809 – some 20 years after the American Revolutionary War ended – American writer Washington Irving anglicised Sinterklaas into Santa Claus.

A Dutch poem from 1810 names Spain as his home, including his gifts of oranges:

Saint Nicholas, good holy man!

Put on the Tabard, best you can,

Go, therewith, to Amsterdam,

From Amsterdam to Spain,

Where apples bright of Orange,

And likewise those [pome]granate surnam’d,

Roll through the streets, all free unclaim’d

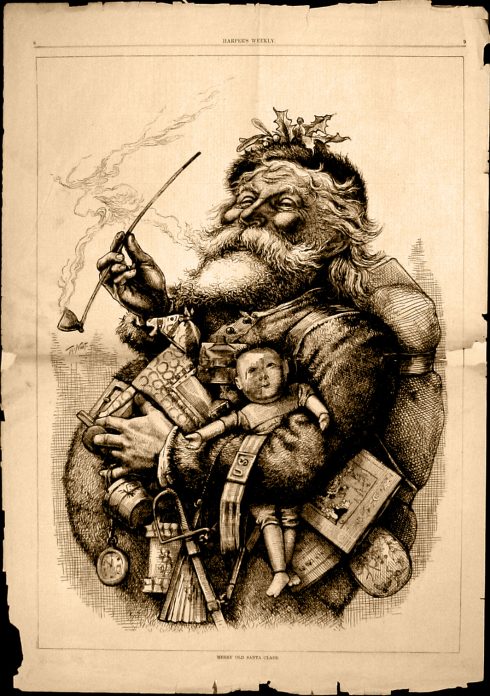

The Bavarian illustrator Thomas Nast later drew fictional scenes from the jolly Santa Claus’ life in the magazine Harper’s Weekly, which depicted Santa Claus in red-and-white robes, with a red-and-white hat, a white bushy beard, a pipe in one hand and gifts for children tucked under the other.

It wasn’t until 1927 that a Finnish radio host claimed he’d found Santa Claus’s house – in Korvantunturi, a mountainous region in Lapland shaped like the ears of a rabbit.

Additions to the Santa Claus story later spread the iconic figure all across the world as the date of present giving also shifted from December 6 to December 25 to coincide with the birth of Jesus.

Today, no one would link like the sun-drenched city of Alicante with the story of Santa Claus.

But for the Dutch it remains his first original home – pure mythology to scrooges, but the central figure of Christmas for countless others.

READ ALSO:

- Roscon de Reyes: What you should know about Spain’s traditional Christmas cake

- Snails and thistles: These are the weird and wonderful regional Christmas dishes eaten across Spain

- NAVIDAD: Nineteen things you (probably) never knew about celebrating Christmas in Spain

Click here to read more Alicante News from The Olive Press.