NEW animal welfare legislation has grabbed the headlines for classing pets as sentient beings – but now the governing PSOE wants to introduce a massive loophole.

The new law considers pets to have feelings and be more like children than objects, in the legal sense, and has been passed by Congress.

Under the concept of mistreating a sentient being, owners who have been convicted of animal abuse could potentially have the custody of their children denied. The emphasis is supposed to be on the wellbeing of the animal.

But now the PSOE wants to amend the incoming laws to exclude ‘non-pets’ – potentially the most abused category of animals.

The ‘non-pets’ category would include dogs used for hunting, sports activities, falconry, and herding, as well as rescue dogs. The intention is to provide these animals with ‘specific legislation’, in line with European standards.

Patxi López, parliamentary spokesman for the socialists, said this move is to prevent ‘wrong and ill-intentioned interpretations’ of the new laws. Critics, however, say that the government has bowed to pressure from hunters and wants to placate voters in rural areas by exempting their dogs.

The PSOE’s idea is that excluded animals would come under a specific law, such as a National Game Management Strategy. As a result, the Animal Welfare Act would legislate only for ‘pets that live in a house with their owners’.

Campaign groups, including PACMA, have been protesting about the exemption, with 21 demonstrations taking place throughout Spain.

What will happen next?

The parliamentary processes for the new animal rights laws are grinding onwards. The consultation process initially lasts two weeks, although it can be extended. Later, the amendments proposed by Spain’s political groups will be debated. Podemos and some other parties dislike the proposed amendments about hunting and working dogs and think these should be withdrawn.

Finally, the entire text of the incoming law is voted in Congress and passed to the Senate. If there are no changes, it is approved, otherwise, voting happens again in the lower house. The General Directorate for Animal Rights is hopeful that the process will be finished during 2022.

Meanwhile, the penal code is being revised to increase the penalties for animal abuse, from a maximum of 18 months in prison to 36. This might fall short of some people’s expectations in a country where 200,000 animals are abandoned annually.

What are the new rules for Spain’s pets?

In the case of domestic pets, the new rules have been receiving a mixed reaction. Incoming laws will insist that owners apply for pet DNI cards, rather like our TIEs. To ensure that they know their ‘patas’ from their ‘pulgas’, new owners will be obliged to complete online training courses – although this could be unfortunate for anyone who isn’t tech-savvy (the infamous digital divide).

With the legislation that’s already in force, animals can’t be sold in pet shops and it’s no longer legal to adopt a pet that isn’t microchipped – for example, to take one that is found wandering the streets. The correct procedure is to call the authorities to transport the animal to an approved shelter.

This is causing debate – partly because of a prevailing belief amongst animal lovers that some ‘approved’ shelters euthanise pets that aren’t found homes.

Another rule restricts the reproduction of pets to registered breeders. Owners who aren’t on the kennel register were previously limited to a maximum of five pets, although this law wasn’t applied before, and won’t be applied retrospectively. It’s clearly going to be difficult to monitor pet ownership, especially if families register them under multiple names.

Other rules stipulate that pets must be well cared for and treated ‘like a member of the family’. It is illegal to leave dogs alone for more than 24 hours, leave them in cars, confine them, restrict their movement, mutilate them for aesthetic reasons (such as cropping ears and tails), fail to de-parasite them or remove their farces, use them for begging, or subject them to excessive work.

You cannot dump them, release them permanently into the ‘natural environment’, eat them (!), or put down healthy animals because you no longer want to be their owner.

The ‘adequate care’ rule, however, is arguably something that should apply to all dogs – not just pets.

Spain’s history of animal abuse – the social mores

According to animal rights activists, the problem with Spain’s historic animal abuse problem is down to social mores and this doesn’t have an overnight solution.

Linda Raine of Valle Verde animal rescue in Alumnecar says there has always been adequate legislation to protect animals but that Spain doesn’t have the right mentality behind enforcement.

The Olive Press has heard anecdotal reports of Seprona’s reluctance to prosecute negligent owners, even repeat offenders. For example, the reporter is aware of a harrowing case where two dogs owned by a woman with mental health issues were starved to death on a roof terrace, and all the neighbours were aware of the situation. The police were informed but did not intervene. There is also a well-known case of a horse owner starving several animals without being denounced.

Some critics of the new legislation say that only law-abiding owners will follow the new rules. Those who always mistreated their animals will continue in the same manner.

The situation for Spain’s working dogs

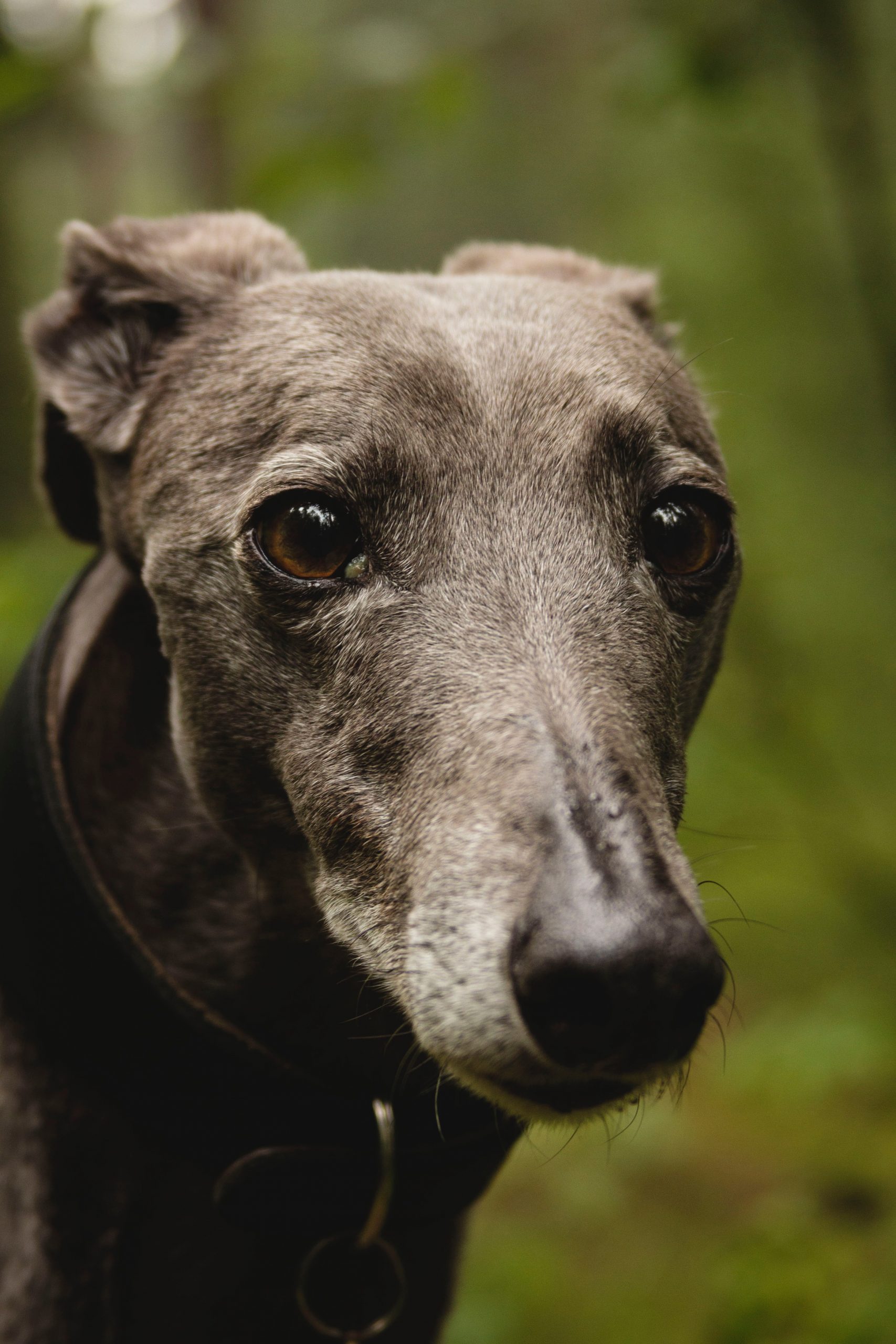

Dogs used for sports, hunting or as ‘breeders’ are frequently culled by their handlers when their so-called ‘useful life’ is over: these animals are most at risk.

Tanya Grenfell Williams, who has three rescued

Galgos, says: “The hunting lobby is very powerful, and the rescue centres have battled for many years with the government and hunters to stop the atrocities, such as digging out dogs’ chips when they are no longer wanted. I think the proposal to use EU laws for this sector is to avoid each autonomous community passing a watered-down version of the Spanish law. Although I disagree with a distinction between domestic animals and sporting animals, the Galgueros would not comply with the new law and adhering to some EU laws is better than nothing.”

Elizabeth, who ran a dog rescue shelter in Mallorca, said: “At the end of the hunting season, we would routinely find five Podencos hanging from a tree together, dead.”

Luz María Puga Blanco, president of the NoMayapa rescue centre, says: “The law says that pet dogs will be part of the family but hunting dogs are not. What is the difference between one and the other? Everyone feels the same; this is the worst of the new law. And the hunters’ dogs are the most abused, then the shepherds’ dogs.”

A public education campaign, like for domestic violence

With Seprona realistically unable to monitor Spain’s vast swathes of ‘campo’, where dog abuse can be hidden from view, owners need to change for the better. For example, they could sterilise their females rather than dumping unwanted puppies into the nearest ‘acequia’ or bin.

Public castration programmes are important – such as the one NoMayapa carries out in La Alpujarra, giving owners an affordable option to avoid unwanted litters.

Luz says: “Regarding the new law, we believe it’s good that sterilisation is mandatory, but we do not trust this since the chip has been in place for years. This is also mandatory and many people don’t chip their animals.”

Perhaps a parallel can be drawn with Spain’s history of domestic violence, and how this problem has been tackled at government level with a zero-tolerance campaign, running across every town and village. Without such a campaign, how can we expect the prevailing attitude towards animal abuse, dating back centuries, to change?

Freya Ruth Rogers says: “The campo men don’t like to be embarrassed, not even over animal abuse. So, if younger generations change their attitude, there is hope.”

Says an anonymous reader: “Thanks to the ‘violencia de genero’ campaign, ‘machista’ men, who would previously have thought nothing of hitting their wife or girlfriend, now give it some consideration. Not only could they go to prison for three years over a domestic violence conviction, but it’s considered socially unacceptable amongst their male peers. We need this to be the case with animals.”

Without public education alongside better enforcement, it seems that some of Spain’s dogs will literally be sold – or thrown – down the river.

READ MORE

Spain’s government takes action to stop controversial fiesta where bull is stabbed with spikes and hooks

ANALYSIS: will new animal welfare laws do enough to change attitudes in Spain?

Click here to read more Must Read News from The Olive Press.