WHEN it comes to popular representations of bandits, gangs, and other notorious outlaws, English-speakers might initially think of England, with the legendary tales of Robin Hood and his merry men cheerfully battling the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Or perhaps the street gangs of the early 1900s recently made prominent by TV show Peaky Blinders capture the imagination more.

With an eye on the silver screen, the infamous cowboys of Hollywood’s ‘Western’ films also come to mind.

But it turns out that Spain has its own equally rich history of bandits complete with movies, a museum, and most importantly, the legends of the bandits themselves.

While they were active all over Spain, the most romantic – and dangerous – were to be found in the remote, wild and rugged mountainous terrain of the Serrania de Ronda in Andalucia.

The history of bandoleros in this region dates back to the early 19th century, when the harsh lives of Spanish peasants meant some chose to live beyond the law, setting up camp in the various valleys and caves that dotted the area.

In those early days, many of the bandits were seen as heroes among the locals, because they often preyed on the rich and gave some of their spoils to the poor – or at least splashed the cash in bars.

The region even became a tourist attraction as many traveled the area hoping for an encounter with the fabled bandits. Indeed, it was not unknown for ‘confrontations’ to be arranged in advance so that young ladies and gentlemen on a grand tour of Europe could safely experience the thrill of being ‘held up’.

And there is no doubt that some of these bandoleros played up to the image of being gentlemanly highwaymen with exquisite manners, dishing out compliments at the same time as relieving young ladies of their valuables.

But while much has been written about these origins, how the era of banditry came to an end also makes for a fascinating story.

It turns out that while the locals celebrated the bandits, Spanish rulers were less keen, especially because those who became bandits were often already criminals escaping justice.

And of course the ‘romantic image’ was totally unwarranted in many cases. Kidnapping, torture and murder were common pastimes amongst the bandits.

So much so that in 1844, the monarch Isabel II formed the Guardia Civil with the explicit purpose of eradicating these bandits for good. The task took almost 100 years.

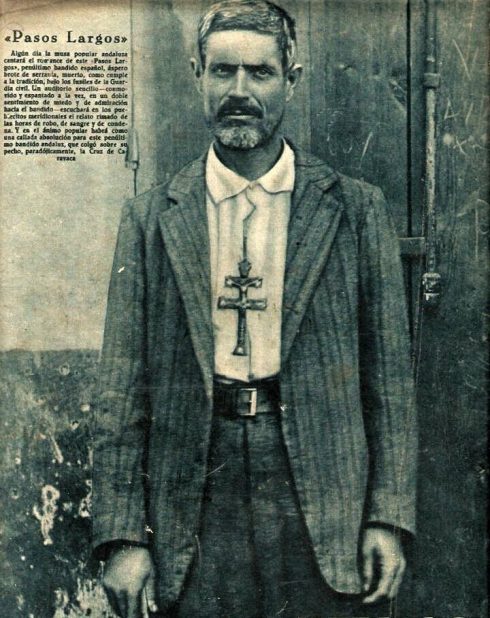

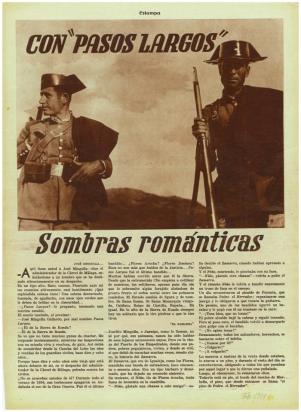

Juan Jose Mingolla Gallardo, more commonly known as Pasos Largos, has the misfortune of holding the title of the last bandit of Andalucia. His death at the hands of the Guardia Civil in 1934 marked the end of the banditry era.

Pasos Largos (which translates roughly to ‘long steps’, a reference to his unique style of walking) was born in 1873 in Los Empedradas, a small village between the towns of El Burgo and Ronda. In 1895, he traveled to Cuba to fight for Spain in the Cuban War of Independence.

When he returned, he discovered that his family had moved on without him, so he struck out on his own.

Pasos Largos’ crime-filled new chapter began with poaching and a gambling habit which led him to get in numerous fights with the local people.

During this time, tales of his exploits spread throughout Spain. One story says that he managed to disarm members of the Guardia Civil, but sent a boy along to return the weapons, as he feared the officers would be punished by their superiors.

But the dark side of his character was never too far away.

He kidnapped a wealthy landowner and received a ransom of 10,000 reales and he is said to have ‘toyed’ with the mayor and other officials in Ronda.

His notoriety was confirmed when a landlord reported him to the Guardia Civil. Pasos Largos suffered a severe beating from the officers, after which he was arrested for a short time.

Upon his release in 1916, he immediately exacted revenge on the landlord who had turned him in, killing both him and his son before escaping to the mountains once again.

At this point, the Spanish government made it a priority to capture him.

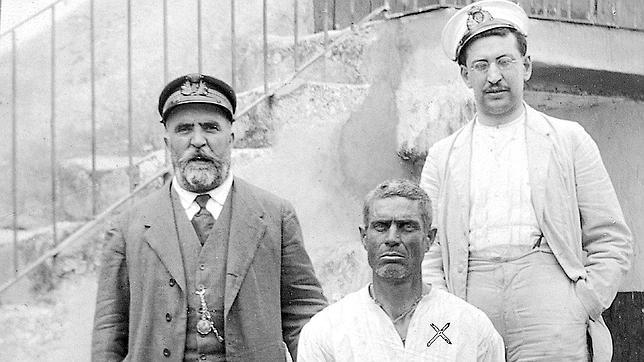

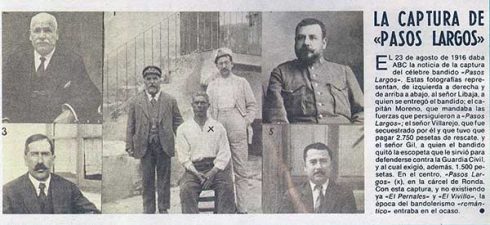

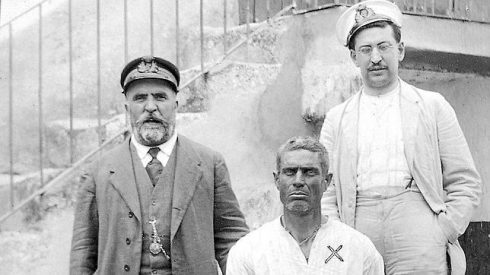

A few months later, they succeeded after Pasos Largos suffered another betrayal when a local woman turned him in to the police. He was then in a shootout with police that left him badly injured. Despite initially escaping, he decided to turn himself in given the severity of his injury.

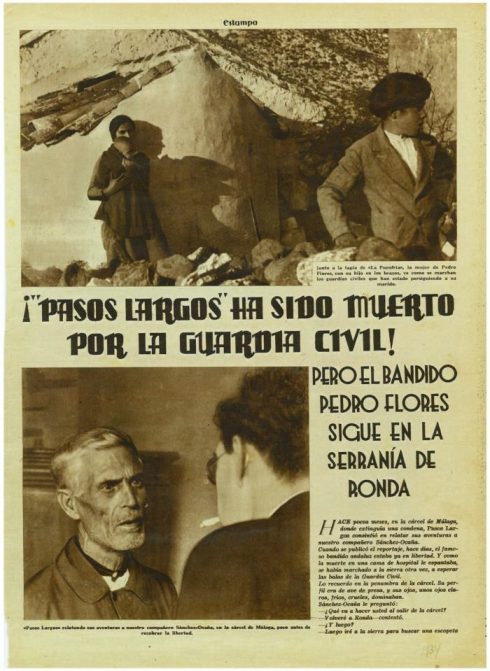

After years on the run, Pasos Largos now faced life in prison. It is said that people cheered for him as he was taken to jail. He remained popular and a bit of a celebrity, often making the pages of the press.

In 1932, after 16 years behind bars, Largos benefitted from a turn of fate. Partly because of his popularity, partly because of reforms made to Spain’s penitentiary system, he was granted a release from prison. Naturally, he resumed his usual activities, leading him to once again be targeted by the Guardia Civil. This time, there would be no escape, as he was killed in a shootout in 1934. The Guardia’s initial purpose, it seems, was served: the last bandit of Andalucia had been killed.

How do we know all of this information? Unsurprisingly Largos’s story captured the interest not only of local villagers, but also of many researchers and journalists. Capitalising on his allure, Largos decided to grant an interview to the magazine Estampa while he was briefly imprisoned in 1934, telling his life story, for which he received 1.000 pesetas.

Pasos Largos’ legacy has extended beyond his death. In 1986, the movie Pasos Largos: El ultimo bandido andaluz was released, based on the bandit’s life.

Until recently the Museo del Bandolero in Ronda told the story not just of Pasos Largos but also of the storied history of banditry in the region.

The museum included paintings, historical documents, coins, and other items of interest related to the bandits and their adventures.

It has closed in Ronda but will reopen in El Borge in the Axarquia region of Malaga. So not only has the last bandit left Ronda – so has its bandits’ museum!