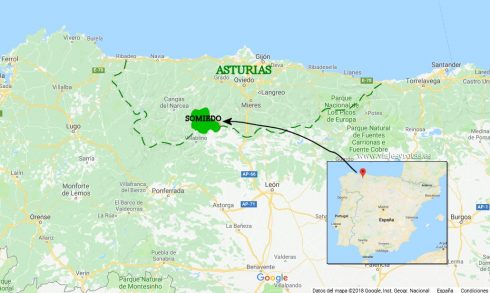

THE mountain road winds up through verdant hills, past picturesque villages, and across broad burbling salmon rivers. We curve through tunnels carved into great rocky crags as we climb up from the Asturias coast into the heart of Somiedo National Park.

We have come in the hope of spotting one of Spain’s most endangered species, the Cantabrian brown bear, an animal that has defied all odds to bounce back from the brink of extinction.

A mere forty years ago, there were fewer than 60 Urso Arctos left in the wilds of Spain.

Much maligned and hunted virtually to extinction, firstly by Spain’s noblemen who came from the cities to shoot them as a trophy to adorn their hunting lodges and then by dedicated bounty hunters who paraded the corpses of bears through villages to collect their dues.

But now, thanks to combined efforts by conservationists, legislation to protect the bear, and a change in attitudes, they have made a surprising comeback and become a beacon of rewilding that has been noticed across the globe.

In the charming hilltop town of Polo de Somiedo, we meet Alicia Madrid Garcia, a wildlife ranger with the Fundacion Oso Pardo (Brown Bear Foundation), an NGO founded in 1992 to promote the peaceful co-existence of humans and bears.

The town is the hub at the centre of the natural park, its wooden buildings nestled in a valley surrounded by dramatic cliffs with vultures wheeling overhead.

As we visit the Casa del Oso, a quaint information centre about bears run by the Oso Foundation, Alicia warns us that summer sightings are rare and that spring and autumn are in fact the best times to see bears.

Although there are at least 80 bears resident within the park itself – of the 400 plus population across the Cantabrian mountains as a whole – they can be elusive especially at this time of year when they are rarely active during the day and are easily hidden within the trees.

“But maybe we’ll be lucky,” she says. “They are terribly fond of cherries which are abundant right now”.

In fact, she spent the previous day harvesting wild cherries to create new plantations in the far reaches of the mountains away from villages.

“It is one of our projects to boost the natural food source for the bears and therefore encourage them away from cultivated orchards where they can come into conflict with human population,” the 33-year-old environmental scientist explains.

Other projects aimed at promoting the peaceful coexistence between humans and bears include providing electric fences to cordon off orchards and protect beehives from raids by sweet-toothed marauders.

Bears are omnivores and in summer some 85% of their diet is vegetarian.

When they emerge ravenous from hibernation in late winter, the females often with young cubs in tow, they will eat carcasses of animals defrosting in the snowmelt.

They move onto fruit and berries, overturn rocks to graze on insects, and this diet is supplemented by small mammals including the occasional goat or sheep pilfered from a wandering flock and of course, honey when they can get it.

Under an EU scheme back by the Spanish government, compensation is paid out to farmers that suffer loss of livestock, hives or crops and in Asturias this has gone someway to lessen the conflict between man and beast, at least more so than in the Pyrenees where brown bear reintroduction has been vociferously opposed by farmers.

For in this region, bears have become a tourism magnate, reinvigorating a rural zone that was emptying out as generation after generation moved to the city.

“Bears are a big draw, an economic resource for rural communities.” admits Alicia, 33. “But so far it is proving sustainable. The sort of tourists that want to come and look at nature also tend to be those who want to do travel responsibly.”

During the last two summers when global travel was curbed as a result of the pandemic, the region saw a boost in domestic tourists visiting from other parts of Spain. “Suddenly people seemed to discover Asturias, they couldn’t explore foreign destinations so they looked closer to home and found adventure here.”

And yet no one would call it crowded. While the rest of the peninsula is sweltering in a July heatwave, up in Somiedo a mist swirls across jagged peaks and on the edge of the tiny hamlet of La Peral, a group numbering little more than a dozen gather on a plateau to scrutinise the hillside across rolling pasture full of wild flowers.

As dusk approaches, we join them to peer through binoculars to scan the landscape on the far side of the valley.

It is my keen-eyed nephew Ralph, who gives the first shout. “There! There!,” he shrieks, pointing to small clearing in the forested hillside, just a few hundred yards above a farmhouse. “I think I see a bear!”

He describes seeing a lolloping beast running into the foliage but the rest of us are sceptical.

After several hours hike with Alicia as our guide pointing out traces of bears, which includes a pile of cherry-pip filled poo, deep lines etched in tree trucks made by the claws of a territorial bear, and hairs collected from a favourite scratching post, we want nothing more than to see one in the flesh.

Suddenly my brother catches sight of something moving between the trees on an adjacent hillside, but it turns out to be two red deer and we all take it in turns to admire their antlers and count ourselves lucky that we have seen any wildlife at all.

Then, just as we prepare to give up and make our way back to the coast in the last of the fading light, we hear an intake of breath from Alicia, as she spots movement in the trees just where Ralph had directed.

She hones in with her scope and we take it turns to peer through the viewfinder.

It is indeed a bear. And not just one, for in the wake of a beautiful big brown bear, her fur glistening golden across powerful shoulders, are two small balls of deep brown cubs gamboling down a rocky scree as their mother scoops up boulders and rolls them over to look for grubs.

We stand enthralled by the scene taking place a good half a mile away on the opposite hillside, but one that feels as if it could be a display for us alone.

Hairs stand up on my neck and the view blurs as I blink away unbidden tears.

“It never stops being exciting,” admits Alicia. “It doesn’t matter how many times you see a bear in the wild, it is always a thrill.”

READ MORE:

- How the brown bear has been brought back from the brink of extinction to thrive in Spain’s Pyrenees

- Off the beaten track: Escape to Arcadia with a holiday in Spain’s northern region Asturias

- Iberian lynx: How Spain brought the world’s most endangered cat back from the brink of extinction

Click here to read more Olive Press Travel News from The Olive Press.