JUST kilometres away from some of Andalucia’s trendiest beaches, Europe’s vegetable garden is cultivating shanty towns.

On route 3108 in the Almeria district of Nijar, Ayoub, a 20-year-old Moroccan working illegally in the region’s ubiquitous greenhouses emerges from the jumble of shacks and saunters towards me.

“Nobody is going to talk to you here,” he says. “Many people come and tell us they are going to save us. They take our picture, but nothing changes. Nothing’s ever going to change.”

Looking dapper given the lack of bathroom facilities, Ayoub decides to show me around. He has been living here since he was 17 and clearly feels at home with his neighbours whose numbers have been reduced by 200 after an arson attack last May.

The landowner quickly fenced off the area and dug it into mounds to deter any further squatting. What remains is even more unsightly than before.

The high fencing lends the place the air of a prison inside which the dust alleys are strewn with garbage, the toilet is a dried-up riverbed and electricity is stolen from the lines overhead. The handful of families and children have gone.

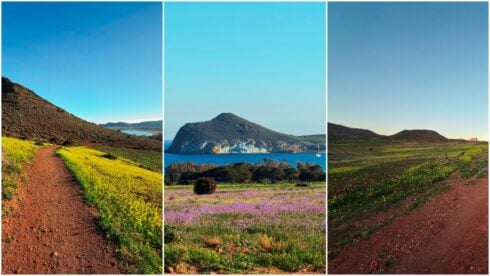

Still here are around 600 men, many from Morocco and Mali. Like Ayoub, they work in the plastic greenhouses that sprawl for miles inland, away from the glittering Mediterranean and the Cabo de Gata natural park where European tourists are blissfully unaware of the harsh reality behind their salad bowls.

The coastline in this province of Andalucia has moved upmarket in the past 20 years and a family apartment now costs upwards of €250 a night in high season.

But while the numbers of vacationing foreigners have taken a knock due to Covid, the numbers seeking work have soared as the economic situation in Morocco and further south grows dire.

According to the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, arrivals by sea alone between January and August 2021 amounted to 15,317, an increase of 56.4% on 2020.

At the start of July this year, more than 800 came ashore in the resorts of San José, Villaricos, Cabo de Gata and Carboneras.

Like the tourists, they come in summer when the weather is better, only they head away from the coast towards the plastic sea where the majority will spray and harvest Europe’s fruit and vegetables in the world’s biggest greenhouse.

According to the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty, Olivier De Schutter, two thirds of fruit and veg consumed in Europe are sourced from here.

Stretching across 31,000 hectares of arid land, the migrant’s “Med” is in expansion and, according to the secretary of the workers union, Comisiones Obreros (CCOO), Maximo Arevalo, 90% of the hard labour is done by migrants. But as this plastic sea grows, so does the housing crisis and ensuing segregation.

Human rights lawyer Ruben Romero from pro-integration NGO, Cepaim, puts the numbers of migrant workers in Almería’s district of Nijar living like Ayoub between 4,000 and 5,000. In the entire province, the numbers may be as many as 10,000.

Regarding pay, Saidou Konkisre, 30, from Burkino Faso says it’s a case of mañana: “Tomorrow. Tomorrow. There’s never money.” Saidou is the first immigrant worker in Spain to see his former employer receive a prison sentence for abusive work practices.

In broken Spanish, he explains how his boss, Francisco Gomez Mas of Joma Invernaderos SL, confiscated his passport and refused to pay him and eight others for long 12-hour days in the Almeria district of El Ejido. At the end of the shift, Saidou was expected to guard the farm equipment in a shed near Roquetas del Mar for which he was promised €10 euros a night.

“The first month, he paid,” says Saidou. “Then he stopped. He wanted to fight us when we asked for our money. My boss now has also not paid me. Now it is over a month late. All the bosses are bad,” he says with resignation.

Saidou has legal status, thanks to his decision to report Joma Invernaderos to the police. But, according to Arevalo, most illegal migrants do not complain for fear of repercussions. “Their bosses tell them what to say during inspections as well as to police or journalists. The farmers should pay €7.28 but they are paying €3 or €4; €5 at most.”

According to Romero, the ratio of good to bad practices among the employers is around 50:50 and is no different in the bio sector, which accounts for an estimated 10% of the 17,000 fruit and vegetable producers in Almeria.

This is backed by reviews on Google: “Welcome to the place where slavery is still current,” says one of Biosabor; and, “There’s bad hygiene but worst of all is the inhuman, degrading treatment on behalf of some of the people in charge,” says another, in reference to Biosol Porto Carrero.

Bio or otherwise, the president of the umbrella association of producers (COAG), Andrés Gongora, is on the defensive. “I can’t say all the farmers are doing the right thing but to put us all in the same sack seems unjust,” he says. “Also, there are processes for filing complaints. This is not a banana republic.”

Gongora also objects to the suggestion that the producers are responsible for accommodation. “The shanty towns break my heart,” he says. “But I think it is a social and political problem and, between us all, we have to ensure it is possible for these people to live in decent conditions.”

In a bid to eradicate at least some of Almeria’s 92 shanty towns, the local Nijar authorities have launched a pilot scheme this year offering 3,000 metres squared on which the producers can house their workers; the area of Ayoub’s shanty town that burned to the ground was 8,000 meters squared.

Meanwhile, several kilometres away, in the trendy resort of San José, hotel owner Joaquin Villegas Rodriguez is worried the night-time landings could damage business. “There may be tourists on the beach who will feel alarmed,” he claims. “Some of the Moroccans coming are delinquents. The Moroccan authorities have opened the jails and are sending them to us as revenge for the conflict over the Sahara.”

Villegas is not the only one in the area who believes these stories. The extreme right Vox party won almost 35% of the vote in the 2019 general election in the district of Nijar and the province of Almeria has been flagged up by the Spanish Ministry of the Interior for a growing number of hate crimes.

Many point to a link between Vox and the farmers, but Gongora doen’t care for it and bristles when I mention the contradictory nature of the alliance, given that Vox wants the illegal immigrants used to pick the fruit and veg deported. “I don’t give tuppence for Vox’s views,” he says. “All the COAG farmers want is for the immigrants to be more easily documented and legalised.”

Legal status generally takes three years in Spain. Ayoub has almost done his time. Hopefully, he will move on to finish his education. With fluent Spanish and the equivalent of the first year of the Spanish baccalaureate under his belt, his prospects are better than most.

READ ALSO:

- 200 homeless and 500 displaced as fire sweeps through migrant worker shanty town in Spain’s Almeria

- Plastic Sea: Almeria’s environmental and humanitarian disaster

Click here to read more Must Read News from The Olive Press.