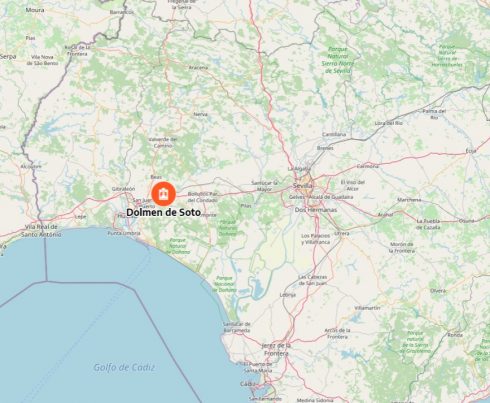

JUST north of the Rio Tinto in southwestern Spain, rising among gently rolling plains are stones belonging to a megalithic tomb dating back some five thousand years.

This is the Dolmen de Soto Trigueros, one of around 1,650 Neolithic burial monuments found within Spain’s region of Andalucia, and an archaeological site that predates Stonehenge.

But while the monument on Salisbury Plain is one of the most visited tourist sites in Europe, the Dolmen de Soto stands isolated, visited only by those curious few tempted off the beaten track.

“If it had been located in the United Kingdom, it would already be one of the most-visited tourist sites,” insists Primitiva Bueno-Ramírez, archaeology professor at Alcalá de Henares University, about the Dolmen de Soto.

The dating so far indicates that the stone circles of Stonehenge were in fact being constructed about the same time as the stone circle at Trigueros was being dismantled while when it comes to size, the stone circle at Trigueros is undoubtedly larger.

However, the stones at Stonehenge are generally larger and heavier than those at Trigueros and there is no indication that Trigueros ever had the equivalent of the lintels that the people who built Stonehenge placed on top of the sarsen stones.

It is tempting to think that, during the 1200 year period between Trigueros being erected and the stone circles of Stonehenge being raised, technology had moved on, allowing the construction of a more sophisticated structure at Stonehenge.

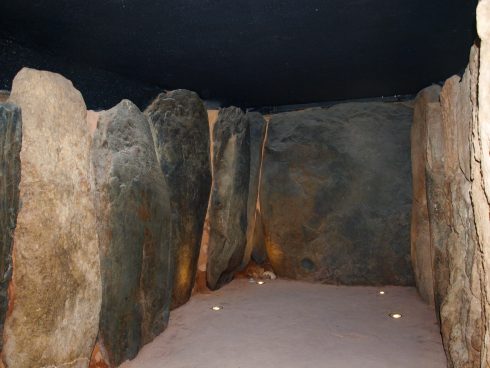

The stones forming the circle at Trigueros were painted a striking red and engraved.

One engraving depicted hunting scenes whilst others were of anthropomorphic figures and symbols.

The original alignment of the vertical stones is not known so it is difficult to interpret the use of the monument. It could have been an observatory to record the phases of the sun or moon, it was, almost certainly, a ceremonial place.

The manpower required to bring the stones to the site and erect them indicates a population from over a wide area and the number of clusters of smaller dolmens in the wider area would support this theory.

Its isolation today does not imply it was isolated when the monument was built. Dolmen de Soto would have been an integral part of a complex sacred landscape that, for the Neolithic people, defined who they were, their territory, how they lived and how they related to their surroundings and other tribes.

The Dolmen de Soto megalithic tomb was built between 3000 and 2500 BC, towards the end of the passage-grave tradition in this part of the Iberian Peninsula.

The dolmen replaced a 65 metre diameter stone circle that consisted of 94 stone pillars, at least one of which was 6 metres tall and weighed 21 tons.

Some of the stones were brought to the site from 30 kilometres away. It is thought that the stone circle was erected about 3800 BC.

Almost a thousand years after the construction of the stone circle, about 2800 BC, something changed in the lives of the Neolithic people and the original symbolism of the circle was either lost or became meaningless in the face of the change.

The stone circle was dismantled, and the stones were used to create the passage tomb of the Dolmen de Soto.

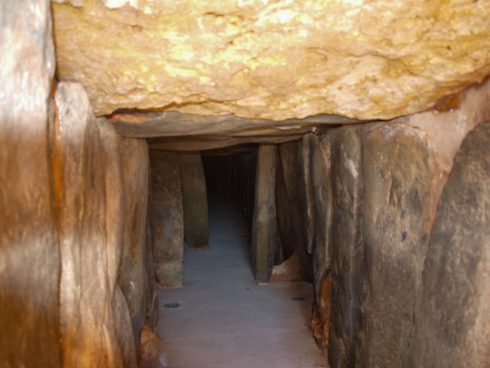

The dolmen is covered by a large mound about 60 metres in diameter and is surrounded by a circle of small stones with a diameter of 65 meters, the original diameter of the stone circle. Inside there is a gallery made up of 63 stone pillars, a frontal slab and 30 other stones that cover it.

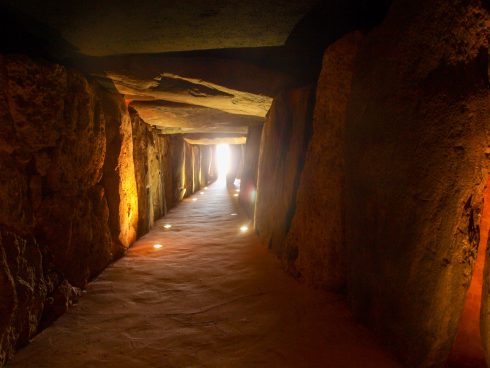

An underground passage, measuring 21.5 metres, starts off narrow then widens to three metres in width and height as it reaches the back of the monument.

The passage is aligned so that, during the equinox, the rising sun lights the interior of the passage and the chamber for some minutes. Some of the original stones were cut to fit into this new construction.

Following its construction, the Neolithic people redecorated and overpainted the stones and it is these newer engravings and images that give a clue as to the change that had occurred.

The new drawings show armed figures. Bueno-Ramírez remarked, “There is not a single megalithic monument in Europe that has so many armed figures on its walls.”

A space within the dolmen has been identified as an area where metal working took place and one figure appears to be wielding a ‘Carps Tongue’ sword, a type of weapon typical of the Late Bronze Age and of the Tartessos culture.

The supposition is that the Neolithic people had been shown or had learned to work copper and this became a major focus of their lives. The timing certainly fits.

For more by Nick Nutter an expert on Andalucia go to his website www.visit-andalucia.com

READ ALSO:

- Ronda: Why this hilltop town in Andalucia is the best inland destination in Spain

- Looking for an adventure? Here are 12 epic walks to take in Spain

- Bathe like Caesar: Visit the stinky Roman Empire site that put Manilva on the map

Click here to read more News from The Olive Press.