WHEN Craig Foster filmed a ball-shaped creature covered with seashells in a South African kelp forest he had no idea the resulting My Octopus Teacher documentary would win a 2020 Oscar and change lives forever.

Thousands vowed to never eat octopus again, including celebrities like Richard Branson, after viewing the sensational bond between man and intelligent sea snail with eight legs.

There are hugs, tears and the tragedy when Craig’s octopus, a female, gives birth and goes the way of all octopus.

The Netflix documentary is now being cited as a driving force behind activists’ effort to block the world’s first octopus farm from beginning production in the Canary Islands this coming summer 2022.

“People who watched My Octopus Teacher will be appalled to discover there are plans to confine these fascinating, inquisitive, and sentient creatures in factory farms,” said Dr Elena Lara, author of a new report from Compassion in World Farming (CIWF).

“Their lives simply would not be worth living.

“That’s why, today, we have sent our report and written letters to the governments in Spain where octopus farming is being developed, urging them to prevent any further development of this cruel and environmentally damaging practice.”

The report Octopus Factory Farming: A Recipe for Disaster says that wild octopus stocks are dwindling in the race feed the world’s biggest markets in Italy, Spain, Greece and Japan, respectively.

But the CIWF say that factory farming is not the solution.

Activists give eight reasons why octopus farming should be stopped, such as their tendency to eat each other in captivity, their incredible intelligence, the lack of any human slaughter protocols and the pressure their carnivorous diet could put on wild fish stocks to feed them.

“The serious environmental and animal welfare problems associated with octopus farming mean that it cannot be compatible with the EU’s new Strategic Guidelines for the sustainable development of aquaculture,” the report concludes.

It comes after Spain’s biggest seafood producer Pescanova has invested €65 million to build the world’s first octopus farm in the port of Las Palmas on Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands.

The 52,000m2 site is near completion as Pescanova – owner of the world’s second-biggest fleets in terms of fishing grounds – aims to begin production next year and produce 3,000 tonnes of octopus annually by 2023.

President of the Las Palmas Port Authority port Luis Ibarra said it was ‘the biggest private investment’ in the history of the port which will create 450 jobs and make the Las Palmas’ harbour – La Luz – the world’s biggest exporter of octopus.

Pescanova’s CEO Ignacio Gonzalez also said that ‘wellbeing’ is a top priority for the company that also won 3rd place in the 2021 Seafood Stewardship Index 2021.

It was the only Spanish corporation and the first-ever fishing business to appear in the list of the world’s 30 most sustainable companies.

The company is yet to reveal exactly what the octopus tanks look like, what ‘toys’ they claim to use for stimulation and what source of food they will rely on.

On paper, however, the aims are noble.

Pescanova’s home of Galicia is famous across the world for giving its name the Spanish dish pulpo a la gallega, made of sliced octopus fried with potatoes and smoked paprika.

But prices of Galicia’s Atlantic octopus stocks have skyrocketed from 12 to 50 euros a kilo in recent years as stocks crashed to make up just 3.5% of all octopus consumed in Spain.

Yes, that means the Pulpo a la Gallega you’ve been eating is actually African. More specifically, Morocco illegally fishes the lucrative crop in disputed coastal waters off the world’s last-remaining colony of Western Sahara.

The 3,000 tonnes of farmed octopus in the Canary Islands will outpace Galicia octopus exports (2,130 tonnes in 2019) but still make a small dent in Spain’s annual octopus consumption of 600,000 tonnes.

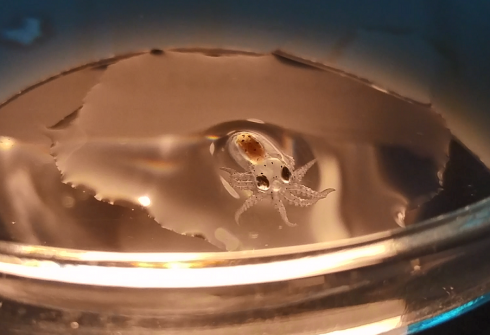

The breakthrough in octopus farming came in 2019 when researchers from Pescanova in Galicia succeeded in making the first-ever octopus reproduce in captivity.

The octopus was called Lourdes, and the feat dubbed the ‘miracle of Lourdes’ after the French pilgrimage site.

While in the wild an octopus has a 0,00001% chance of survival, Pescanova predict a 50% rate of survival in specialised tanks.

“We will continue to investigate how to improve the wellbeing of the octopus, studying and replicating their natural habitat to begin commercialisation in 2023,” Gonazalez said following the breakthrough.

Across the world around 50% of all fish consumed comes from aquaculture, and that figure is set to rise to 66% by 2030, according to Pescanova’s Biomarine Centre director general, David Chavarrias.

READ MORE:

- Police free 260 kilos of live octopus caught in illegal traps in Santoña, northern Spain

- Animals in Spain awarded new legal status as ‘sentient beings’ rather than things

Click here to read more Environment News from The Olive Press.