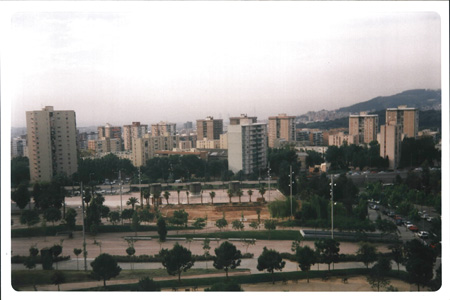

WHEN 5,000 poor and middle-class families received free apartments outside Barcelona in 1974, it seemed the government of fascist dictator Francisco Franco was revolutionising Spain’s housing crisis.

Not only did apartments have three or four bedrooms for larger families, but Ciudad Badia promised all its own shops and services and sports facilities that any parent – many living in wooden shacks – could want.

The streets were even built in the shape of Spain.

Ciudad Badia was the essence of Franco’s dream for the country; the town had a Catholic church at its centre, to represent Madrid.

Communal parks stood in view of hundreds of high-rise windows to keep an eye on mischief, while civil servants had large lower-floor apartments to monitor working class families in smaller apartments above.

Each building also carried the fascist phalanx symbol to instil gratitude to Franco’s government.

But if Ciudad Badia was a model for Franco’s vision for the country, its collapse into drugs and decay are a lesson in why it wasn’t such a great idea.

The first blunder came after Franco’s ministry for housing finished the 5,732 apartments in 1974, a year before the Generalissimo’s death.

To start with, constructors fell short of the planned 12,000 apartments because the map of Spain only just fit between two large motorways on the site.

Badia still has no connection to either motorway, despite them criss-crossing the municipality.

Until 1976 the ministry went ahead gifting the built apartments to working class families and civil servants, even holding an inauguration with king Juan Carlos I, while forgetting to install any water supply.

The city was a complete ghost town for its first two years.

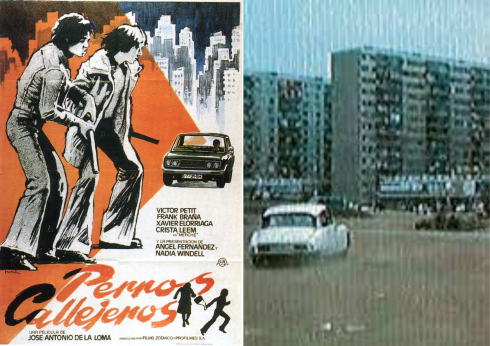

Abandoned high-rise apartments in Ciudad Badia became the backdrop for Spain’s legendary crime thriller Perros Callejeros, about a gang of car thieves from Barcelona released in 1977.

Ciudad Badia, as the town was originally known, became the setting of Spanish crime thriller Perros Callejeros.

No one had even moved into Ciudad Badia and it was already a symbol of crime.

Once families began moving in, they quickly found the Francoist housing ministry hadn’t built vital services like a fruit and vegetable market, a community health centre, nurseries, municipal offices, a care home, a library, a concert venue and sports facilities.

As one original resident said: “Through the 80s there were no amenities or services and, just like in Barcelona, drugs began to do their damage.”

Part of the problem was the high-rise apartments had special state protection, so homeowners didn’t pay full housing tax (or IBI in Spanish).

No council tax meant the town hall had no funding to install better services.

Badia residents have made headlines campaigning for all the facilities a town of 14,000 needs, and in 1994 succeeded in changing names from Ciudad Badia to Badia del Valles in efforts to leave the association with drugs and violence behind.

Residents also won an agreement with the Catalunya government for €3 million in annual aid to fund development.

But the problem of funding is still present, with Badia’s schools nearly closing in 2012 because the town couldn’t pay the electricity bill.

“There is no money to invest in anything, so the city is getting worse every year. It’s a fish that’s eating its own tail,” said Elizabeth Ruiz, leader of a local association.

To add chorizo to the paella, Badia del Valles is also the town with the highest concentration of asbestos in all of Spain.

Because many arrivals had to prove low-income status to get an apartment, unemployment has remained high and Badia del Valles still has the lowest household income in all of Catalunya.

But the town isn’t all doom and gloom.

Football facilities built thanks to community action produced many top-flight footballers, like Carles Busquets who became Barcelona’s goalkeeper and his son Sergio who plays for the national team.

Many original residents also speak with nostalgia about the collective spirit during Badia del Valles’ troubled origins.

“It was like a village in a city, everybody knew everybody and we won everything we needed: clinics, markets, schools and small businesses,” one resident said.

“Before you could even get into the shops, you’d already chatted to all your neighbours,” said another.

If that was the spirit of Francoist Spain, in Badia del Valles this was achieved not because of but in spite of its construction.

READ MORE:

- Barcelona town puts pigeons on the pill

- Court halts efforts to remove Franco monument in Catalunya after campaign by locals

- Spain’s Palma de Mallorca ‘erases’ Franco’s memory by renaming streets linked to dictator

- Melilla makes history removing ‘last statue of Franco in the public sphere in Spain’

Click here to read more Must Read News from The Olive Press.