AT the end of a dark, narrow cobbled track I finally found the collection of derelict buildings, suffocated by knee high weeds and weighed down by history.

The former East German box factory, near the tiny Saxony village of Neuwegersleben, was one part of my journey into the heart of darkness that I couldn’t avoid.

It was here that the prime suspect in the Madeleine McCann case Christian Brueckner invested €36,000, through an auction in Leipzig, and here that police found up to 20,000 sickening photos and videos he had hidden in a Lidl bag under the body of his buried dead dog Charlie.

I arrived on a sunny afternoon to find nobody else about, although I recognised it from a number of press reports. It had taken some time to find the site, which spread over quite a number of hectares and its rusty old gate was chained shut and had a ‘Stop’ sign alongside it.

ORDER THE BOOK FROM AMAZON HERE

It was walking into the wide open expanse that you began to realise what an incredible opportunity this could have been for a pervert like Brueckner, 44, who officially told friends that he wanted it to be a car repair garage or some sort of sculpture garden.

As Chief Prosecutor in the case Hans Christian Wolters told me the following day: “If you want to sexually abuse kids, that is the right place, as nobody would see or hear anything. There are no neighbours!”

The site was divided into a grid of concrete squares and comprised around half a dozen buildings. The first thing I noted was the amount of underground areas, suggesting that it was once used for something rather more sinister than making boxes. Perhaps armaments. There were dozens of openings that led down to dark spaces, some interlinked and others full of rubbish.

I clambered into the first building, which had a collapsed roof and rubble piled up at least a metre high. On one wall the word Arbeit (job/ work) and two shorter words could just about be made out, not dissimilar to the words on the entrance gate at Auschwitz concentration camp: Arbeit macht frei (work sets you free).

I slowly wandered about the various buildings looking for anything of relevance until I stumbled across a side annexe with four huge plastic vats, presumably used to store the diesel that Brueckner stole on many occasions.

Next to it was another small annexe with one big, heavy garage door slightly ajar. I pushed it open and wandered in to find a pair of dirty mattresses propped up against the wall, a tub full of empty alcohol bottles and a pair of broken women’s sunglasses.

Could this be where Brueckner made some of his videos? Did he keep women, even children, chained up here?

There was only one small window with reinforced glass, so this would be the place for it, and given his 2013 Skype chat with his online friend panickspatz66 about ‘capturing something small’, it would fit the bill. ‘Particularly if evidence is destroyed afterwards,’ he had replied to his pal.

READ ALSO: The six sex crimes Madeleine suspect Christian Brueckner is facing in Portugal, Belgium and Germany

Shallow grave

I had those words etched in my brain so when I wandered to the back of the small annexe I did a double take. Looking recently dug up, and certainly not appearing in a single photo or video I had seen of the box factory, was what looked like a shallow grave, about 5ft in length and a foot and a half in in depth.

A pile of rubble, with chunks of concrete at the bottom, was next to it, while an empty bottle had been thrown in, almost for decoration. It was extremely sinister.

When I later brought it up with the prosecutor in nearby Braunschweig, he refused to be drawn on what they had found at the box factory, only admitting that they had recently been back.

The industrial site would have been one hell of a job for the police to examine and, it was reported that 100 of them had been in situ for the first few days of the search which began on January 14, 2016.

All around the site I found holes in the ground, openings leading to cellars and tunnels. Some areas had obviously been excavated by police, while many others appeared to have been ignored. But that is only guesswork.

The downright spookiest building was probably once the factory’s main office and it was the most intact.

I pushed open the door to go in and found a trapped bird flying around and tried to let it out, unsuccessfully.

This had obviously been the hub of activity and according to one of Brueckner’s friends Bjorn, who I talked to later, this was where he stored most of his stolen goods, including dozens of computers, solar panels and many other items. There were pots of paint, cutlery, countless chairs and tables, over a dozen computer monitors. A nasty looking circular saw cut into a workbench.

There was a kitchen, two bathrooms and a big room with dozens of shelves, which had up to 1,000 books on them (many more were strewn on the floor), as well as hundreds of old records, presumably all once stolen by Brueckner, including one by Barry Manilow, which I imagine wasn’t his taste.

The weirdest thing I found as I sifted through the cornucopia of neglect was a large series of circular symbols sprayed on the floor at the threshold of each room, a neo-Nazi-type Celtic cross in an electric orange colour.

They appeared to have been added recently, probably sprayed by police as they finished inspecting a room in the latest search.

With dusk falling I took my leave, not wanting to be stuck here at night and with an appointment already made with friends of Brueckner’s in Braunschweig, an hour’s drive away.

Braunschweig, I later learned, was where Adolf Hitler had been given citizenship in 1932 to allow him to run in that year’s German presidential election, and he was rewarded with a series of ministries once the Nazis took power the following year.

This included the Hitler Youth and even the SS training schools base, while a number of key armament factories were set up around the area.

It would certainly make sense that the nearby site in Neuwegersleben was one such facility. It would make more sense to blow the place up once the investigation into Brueckner is finally completed.

READ ALSO: The first extract from My Search for Madeleine by Jon Clarke

GO TO GRANADA!

It was two weeks after Christian Brueckner had been made a prime suspect into the Madeleine McCann case in June 2020 that I received a call from the Mirror to dig into him in Spain.

Talk about coincidences. I was actually reading a book about Orgiva, the Granada town, which I’d dubbed the ‘Glastonbury of southern Europe’ (and where, coincidentally, the Olive Press was born) when the reporter in London asked: ‘Can you get to a place called Orgiva?’

I almost fell off the sofa.

‘It’s where Brueckner’s friend Michael Tatschl lived for many years, the guy he went to prison with. I’ve tracked him down on Facebook and he would make an excellent interview.’

Despite omitting the fact that his Facebook page actually showed him leaving Orgiva in 2016 – or that his featured image showed him snarling at the camera with his middle finger sticking up – it was definitely worth the three-hour drive into the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Most of all though it came as a real Eureka moment when two dots itching to be joined were finally united as a concrete certainty: the hippie hangout of Barao de Sao Joao in the Algarve, where Brueckner lived for some time, now had a direct crime link to Orgiva, the new age capital of Spain.

I had long had a feeling Brueckner would have links to Orgiva, with its little-checked, free-spirited community of international travellers tucked away in a string of hidden valleys.

The Alpujarras is a region I know well having come across the fledgling Olive Press there in its first few months, while writing a travel article for the Mail.

READ MORE:

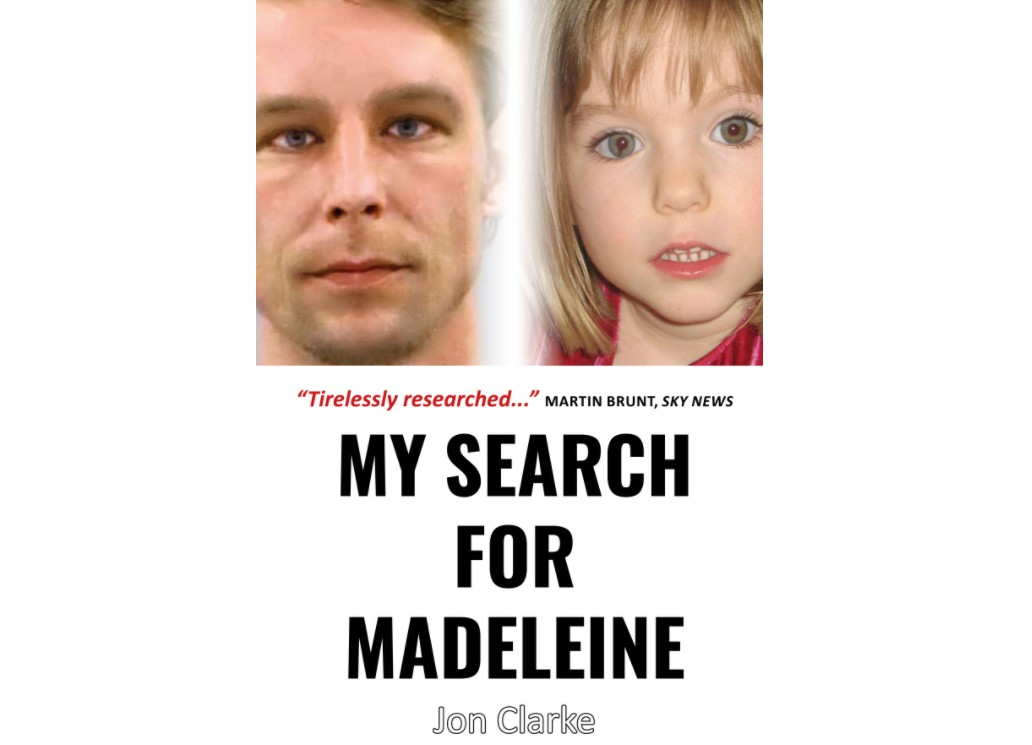

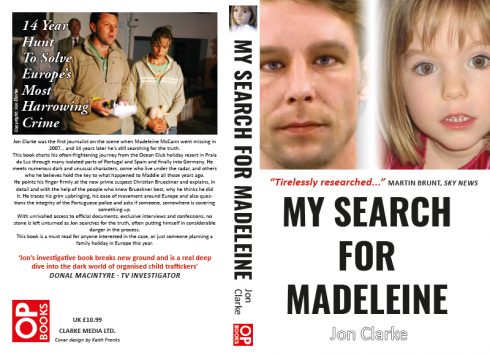

- New book explores 14 years of investigating Madeleine McCann case by the Olive Press in Spain and Portugal

- Troll campaign on Amazon aims to stifle sales of a new book on the Madeleine McCann case

- ‘Tirelessly researched’ new book on missing Madeleine McCann is a deep dive into murky world of Spanish and Portuguese costas

Click here to read more Crime & Law News from The Olive Press.