IT’S oddly invigorating to wake up at seven in the morning with a hangover and sleep deprivation, and then put yourself in the way of terror just for the fun of it.

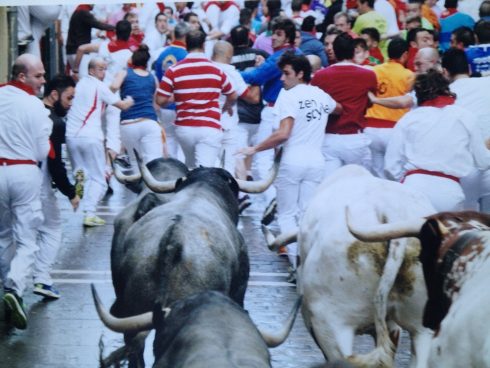

That’s what happens when you go running with six half-ton fighting bulls at Pamplona’s famed San Fermin festival.

It will be around 7.15am when I stroll up to the barriers by the old Hostal Marceliano, now a civic building, and greet my friends who will also be running the bulls that morning.

A fair few will be reading the morning paper where that day’s bulls are presented, analysing their attributes, including horn slopes and fur colour while sipping coffee. I pretend to note the details trying to look far more relaxed than I feel.

The agony of the last 30 minutes before the rockets blast at 8am, (when the bulls are released) and your life is quite possibly on the line, is nearly unbearable.

But for me, there is (usually) no turning back.

It just so happens my father, Matt Carney, was the first foreigner famed for his bull running skills.

An Irish-American WW2 Marine Officer who was shot and wounded on Iwo Jima, he started his career at San Fermin by meeting and getting in a fist fight with Ernest Hemingway. That’s a longer story, but let’s just say, they both deserved it.

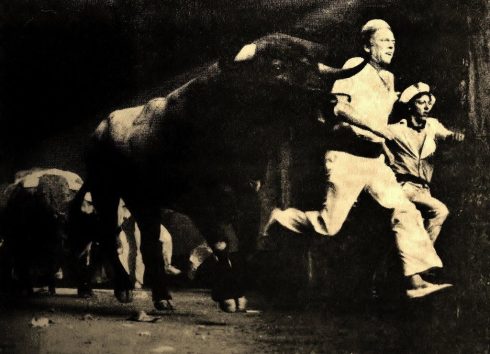

He ran as well as the Navarrans, the Navarrans used to say and he did it for 30 years from the 1950s to the 1980s.

I have seen photos and videos and it is true. He was graceful, he seemed fearless, he smiled transcendently, and he had timing. He was never running away from, but actually running with the bulls, which is exactly the point.

The way he described it, it was an act of spiritual convergence with the herd, of being accepted by them. You are not the antagonist, but a brother. You may run side by side, or ‘on the horns’ meaning right in front of the bull, in perfect rhythm. It’s spectacular athleticism mixed with mental acuity and bravery. It is pure joy, better translated in Spanish as alegria.

When I was a child I asked my dad if he would teach me how to run and he said: “Why sure – when you’re old enough. Just, uh… just don’t tell your mother.” I will never know if he meant it as he died shortly after when I was still little.

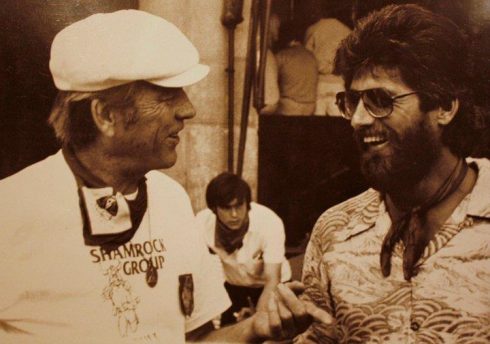

In my late teens and early twenties I attended San Fermin but I just wanted to party. I finally went to learn about the bulls with my dad’s old friend, Bomber (“Don’t yell my name in an airport”, he used to say).

He had long white hair and sunglasses he never took off. He was the first person to agree to show me the way of the bull run, or encierro, as it’s known in Spanish. “Because that’s what your dad did for me and others,” he told me.

He plonked me in a corner of the encierro (the streets barricaded for the run), and then the rockets blew, the crowd surged and the bulls literally flew by clopping on the cobblestones.

When they were gone and I was left standing there, apparently still alive, there was no feeling like it. I was hooked.

That was in 2010 and after that I moved to Spain and started going to smaller festivals around Navarra and running in places like Tafalla, Larraga and Estella, trying to learn more.

I had days when I was braver than others. I had runs where I slunk out just after the rocket, not feeling it, and somewhere along the line I managed to get accepted into this colourful group of bulls and men.

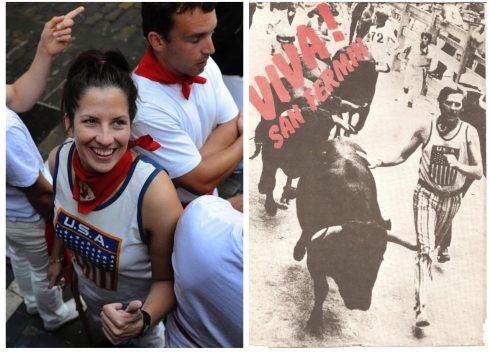

This endeavour seems to attract mostly men. The best answer I get to why women don’t run the bulls is simply that they are not that stupid.

It is rather pointless in a concrete way, though perhaps not in a traditional-ritual context. Male chauvinists claim us women are not physically or mentally equipped to run with the bulls. However, on any given morning, neither are many of the male participants.

And then there are the young male foreigners who are often full of bravado but completely clueless as to what it all entails.

The most clear danger I was ever in was in 2014 when an infamous Miura, among the fiercest breeds of bull, slipped and fell at the back of the herd.

A bull on its own will become relentlessly aggressive. This one was no exception and I had also tripped and fallen just ahead of him. The bull, named Olivete, looked at me and then gored an Australian and two or three more guys right in front of me.

Somehow I survived by standing stock still like a statue plastered against the wall. The game is Don’t Move a Hair.

I was wearing a ridiculous linen jacket and had make-up on, because my father had apparently worn a suit out of respect for the Miuras. I felt absurdly overdressed but thought grimly, if you get gored by a bull, you might as well look your best.

The street had cleared considerably and only the most experienced runners were left trying to entice the bull away from those of us stuck along the walls. People on the balconies screamed above us in unison each time the bull charged someone. Reality shifted to a dreamlike quality.

After a surreal amount of time, I managed to sprint up the street in bursts when the bull was not looking my way, finally sliding through sawdust and grime under a barrier to safety. The adrenaline rush from that left me shaking on and off for hours, even after a couple of glasses of brandy.

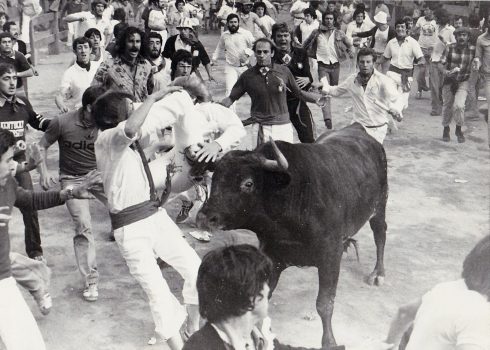

My father was gored in 1977, incidentally by a Miura, not long before I was born. I watched a video of him speaking about it from the hospital, possibly on some very good drugs. There was no pain, he said, just that feeling of blood flowing out of his leg, of life flowing. It reminded him of being wounded on Iwo Jima.

He told the interviewer that he simply went deep into himself and remained calm – it was unfolding as it should unfold. I grew up with a graphic photo of the goring on my living room wall, my dad swinging by his leg on the bull horn (see photo), which gives a kid some life perspectives I guess. He loved that photo.

In a world so driven by the fear of death and an obsession with safety, some people still seek the feeling of confronting it.

It’s a ritual played out in many different ways across human cultures. This ritual happens to be one of the most exciting and dangerous still left on the planet.

A lot of the foreigners are veterans who have seen battle and many say the bull run is therapeutic for them. “I can finally feel something again,” one told me having seen unspeakable things as a medic in Afghanistan.

As the clock nears 8am, we move somewhere to sing our prayers to the saint San Fermin. I can usually barely stand. I am so nervous – no matter how many times – and we sing: A San Fermin pedimos… We sing once in Spanish, then in Basque three times over, asking that San Fermin protects us in the bull run.

We are ritualistic beings and the communion of being there in this electric atmosphere where fear and adrenaline and joy are all mixed into one overwhelming yet strangely beautiful emotion, is a rare experience and one I will always love.

The final song is sung one minute before the rocket goes. We yell VIVA! GORA! and move to our spots. My hair is usually standing on end. BAM, BAM the rockets go, the pen is opened, and your destiny barrels down on you.

Deirdre Carney is an American writer, photographer and English teacher living in Madrid. For more, follow her on Instagram and visit her website.

READ ALSO:

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.