WHEN I first heard about the ruins of Madinat al-Zahra, I was intrigued by the idea that a palace-city of such magnificence should have lasted for such a short time.

Civilisations come and go, as any reader of history knows but for it to last no more than 75 years seemed a tragedy.

It was the summer of 2001. I picked up a leaflet about an exhibition that was to be held in the museum at Madinat al-Zahra, just outside Cordoba. It was entitled The Splendour of the Cordovan Umayyads. I remembered my childhood love of Tales of the Arabian Nights and I was hooked. So we drove across from Málaga, on a blistering hot day to see what it was all about.

I have been back many times since and the place holds a fascination for me; so much so that it inspired me to write a novel.

I decided to tell the story of the city through a family that lived there; I had the bare bones of my novel before me, in the stone walls and paved paths, in the narrow passages ways, the ornate gardens, the artefacts in the museum. All I needed to do was to make the city come alive through my characters.

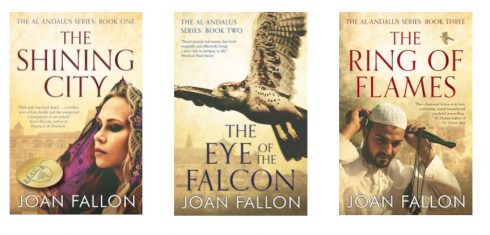

I’ve called the novel The Shining City because ‘Madinat’ (or medina) is the word for town and ‘Zahra’ means shining or brilliant. It’s said that the caliph called the city al-Zahra because, at the time it was being built, he was in love with a slave girl called Zahra. It could be true; there are certainly written references to a concubine of that name, but I think ‘Zahra’ referred to the magnificence of the city itself. As the principal character in my book, Omar, tells his nephew:

‘It means shining, glistening, brilliant. Possibly his concubine glittered and shone with all the jewels and beautiful silks he showered upon her but then so did the city. It was indeed the Shining City.

When visitors entered through the Grand Portico, passing beneath its enormous, red and white arches, when they climbed the ramped streets that were paved with blocks of dark mountain stone, passing the lines of uniformed guards in their scarlet jackets and the richly robed civil servants that flanked their way, when they reached the royal residence and saw the golden inlay on the ceilings, the marble pillars, the richly woven rugs scattered across the floors and the brilliant silk tapestries, when they saw the moving tank of mercury in the great reception pavilion that caught the sunlight and dazzled all who beheld it, then they indeed knew that they were in the Shining City.’

Of course today, looking at the ruined paths, the piles of broken tiles, the reconstructed arches and pillars, we need to use our imagination to see it as it once was.

The construction of the city of Madinat al-Zahra was begun in the year 939 AD by Abd al-Rahman III and took 40 years to complete.

Having declared himself the caliph of al-Andalus in 929 AD and with the country more or less at peace he wanted to follow in the tradition of previous caliphs and build himself a palace-city, grander than anything that had been built before.

The site he chose was eight kilometres to the west of Cordoba, in present day Andalucia and measured one and a half kilometres by almost a kilometre. It was sheltered from the north winds by the mountains behind it and had an excellent vantage point from which to see who was approaching the city. It was well supplied with water from an old Roman aqueduct and surrounded by rich farming land. It had good roads to communicate with Cordoba and there was even a stone quarry close by.

The caliph left much of the responsibility for the construction of the city to his son al-Hakam, who continued work on it after his father’s death.

One of the most curious questions about Madinat al-Zahra is why, despite its importance as the capital of the Umayyad dynasty in al-Andalus, this magnificent city endured no more than 75 years. When al-Hakam died in 976 AD the city was thriving; all the most important people in the land lived there.

The army, the mint, the law courts, the government and the caliph were there; the city boasted public baths, universities, libraries, workshops and ceremonial reception halls to receive the caliph’s visitors.

But al-Hakam’s heir was a boy of 11-years old. The new boy-caliph was too young to rule, so a regent was appointed, the Prime Minister, al-Mansor, an ambitious and ruthless man.

Gradually the Prime Minister moved the whole court, the mint, the army and all the administrative functions back to Cordoba, leaving the boy caliph in Madinat al-Zahra, ruling over an empty shell.

Once the seat of power had been removed from Madinat al-Zahra, the city went into decline. The wealthy citizens left, quickly followed by the artisans, builders, merchants and local businessmen. Its beautiful buildings were looted and stripped of their treasures and the buildings were destroyed to provide materials for other uses.

Today you can find artefacts from the city in Malaga, Granada, and elsewhere.

Marble pillars that once graced the caliph’s palace now support the roofs of houses in Cordoba.

Ashlars that were part of the city’s walls have been used to build cow sheds.

Excavation of the site began in 1911 by Riocardo Velazquez Bosco, the curator of the mosque in Cordoba. The work was slow and hampered by the fact that the ruins were on private property.

Landowners were not keen to co-operate and eventually the State had to purchase the land before the excavations could begin.

The work progressed slowly but gradually over the years a number of government acts were passed which resulted in the site being designated as an Asset of Cultural Interest and in 1998 a Special Protection Plan was drawn up to give full weight to the importance of the ruins.

Today the site is open to the public and has an excellent visitor centre and museum. I can recommend a visit.

Having completed writing The Shining City, I then went on to write The Eye of the Falcon and The Ring of Flames, covering the period that is known as The Golden Age of Moorish Spain.

The three books form the al-Andalus trilogy and are available as ebooks from Amazon and in paperback from bookshops, both local and online. Visit Joan Fallon’s website for all the information about her books.

READ ALSO:

- Patios of Cordoba: Where even the most reluctant gardener will find inspiration

- Walk this way: Why Cordoba should be top of your Spain travel list

- Cordoba’s Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos: Where the Christian, Roman and Moorish meet