A HARROWING past of sexual abuse, addiction and mental institutions was flagged up by his involvement with the new child protection bill, but the musician and author says the experience has only “deepened” his love for Spain, writes Heather Galloway.

Concert pianist, writer and sexual abuse victim, James Rhodes is feeling both relieved and disconcerted: relieved that Spain’s new ground-breaking child protection law has reached Congress at last and disconcerted that it has been labelled the Rhodes Law – the first Spanish law to be named after a Brit.

“I got such a shock when I heard. I was like, ‘You should have told me first, Pablo!’” he tells the Olive Press, referring to Unidos Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias who helped push the agenda.

“It’s not about me. It’s a misconception that I got the law done. The NGOs have been working on it for years. But what the law is called is irrelevant anyway. The main thing is that we have come out of it.”

After signing up to the child protection crusade, James spent three fraught years helping to get the bill agreed upon by the warring political factions.

“It should never have been a struggle,” he says. “This law started with the PP [conservative Popular Party]. It’s the only thing all the parties agree on.”

But what is basically a humanitarian issue got turned into a political football with the right-wing press weighing in and attacking Rhodes, mercilessly picking over his past and even ridiculing his Spanish.

“I don’t hate journalists,” he laughs. “What I objected to were the absolute lies I had to read about myself, particularly when I was sitting in the hospital with my dying mother.”

A household name in Spain, Rhodes, 46, became aware of the scale of sexual abuse, particularly for minors, after moving here in 2017.

When talking about the abuse he himself suffered between the ages of six and 10 at the hands of his PE teacher at his St John’s Wood prep school in London, he insists on using the word “rape”.

It is a subject that has consumed him for most of his life and the workings of the Spanish justice system angered him to such a degree that he told the ABC in 2018, “It makes me sick.”

Prior to the Rhodes law, victims in Spain who felt unable to speak out within the specified time frame of between five and 15 years beyond the age of 18, would miss their window and the aggressor was home free.

Head of Child Policy and Sensibilisation at Save the Children, Catalina Perazzo tells the Olive Press, “The justice system has not been child friendly because it made children relive the whole thing, sometimes up to six times.”

She agrees that the system has meant that the child who went to the police would end up with worse mental health than the child who didn’t.

Rhodes can identify entirely with the silence to which many Spanish victims of sexual abuse have been condemned until now.

“If you spend long enough thinking you will die if you tell your secrets, then you end up believing it,” he wrote in Instrumental, a blisteringly raw read published in 2015 which flew off the shelves in Spain.

“If a rapist tells a five-year-old child again and again what monstrous things will happen to him if he ever tells anyone, it is assimilated, unquestioned , accepted as absolute truth.”

Once finalised, the Rhodes Law will revolutionise the way child abuse is dealt with in Spain while affording James a modicum of peace, along with Bach, his son and his fiancée, Argentinian actress, Micaela Breque.

“To get the law passed was my way of reconciling with myself, forgiving myself and of having the fucking certainty that less children would have to live through what I lived through,” he writes in his new book Made in Spain, published this month.

A love letter to his adopted land, the book is peppered with expletives and strong opinions, yet, in the flesh, Rhodes comes across as a gentle, almost fragile soul with a disarming smile.

“I chose the words I use in the book carefully,” he tells the Olive Press; words that, impressively, were mostly written in Spanish – “I think it’s so disrespectful not to learn the language,” he says.

They are also words that express nothing short of passion for everything from the public transport system to the arts in a country that honoured him with express citizenship at the end of last year.

At least, that’s how it begins. The second half, which gives a blow-by-blow account of his participation in getting the Rhodes Law to Congress and the abuse he suffered at the hands of the press, reads like an “aha” moment, as if he’s finally morphed from tourist to fully-fledged Spanish national.

Asked by the Olive Press if the struggle to pass the Rhodes law detracted from his love of Spain, he says, “No, it only deepened it.” As Rhodes writes about the need to “protect” his new home, clearly this need has been fulfilled.

Due to the abuse he suffered as a child and its corrosive impact on his mental health, Rhodes felt like an outsider in London, taking refuge in Bach and Beethoven and using addiction and self-harm to bury his demons.

Britain became synonymous with hell; Spain has offered him the chance of renaissance.

It is the Spanish and their way of life that have made him feel he belongs at last. Referring to the response to Covid-19 last year, Rhodes tweeted, “Britain is united in its arrogance while Spain is united by compassion. There’s a reason for the different uses of our balconies.”

Now, it’s back to his piano and Mica, an Eminem fan who sent him a message from Buenos Aires on Instagram in 2016 and who now shares his apartment in the upmarket district of Salamanca.

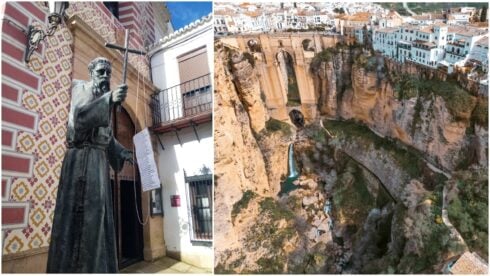

Back too to immersing himself in his music and in Madrid, a city he describes as “something else,” in his book. “When I get close to the city, I notice a wave of emotion that’s so intense, I feel like crying,” he writes.

“A soft voice inside of me tells me that, after everything, after running for so long, trying to escape, of feeling an unimaginable weariness, I’m home. I feel as though I form part of a huge united family.”

READ ALSO:

- Details of Spain’s new ‘Rhodes Law’ revealed ahead of final vote in major victory for sex abuse victims

- British pianist and sexual abuse activist James Rhodes gains Spanish citizenship

- How did a convicted British paedophile move to Spain, dodge criminal record checks and find work as an English teacher?

Click here to read more Must Read News from The Olive Press.