THE last of the Old Masters and the first of the new, Goya may be one of the most celebrated artists in the world with a hallowed place in Madrid’s Prado Museum.

But in the week that marked his 275th birthday (he was born on March 30, 1756), we thought it might be fitting to dig out some of the lesser know facts about the iconic Spanish painter.

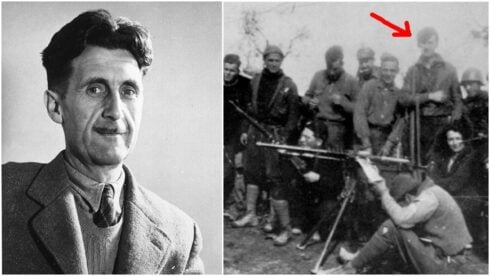

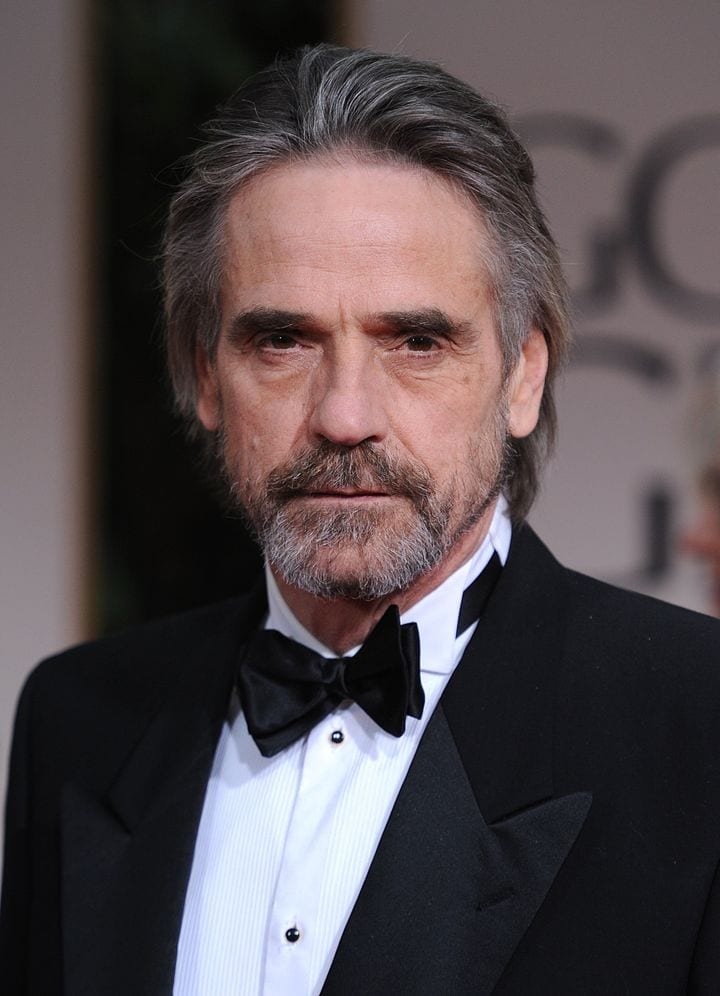

Take Jeremy Irons for example, who potrayed the painter in a recent biopic.

The Dead Ringers actor suggested that Goya’s interest in ‘satanism’ and an apparent dabbling in ‘homosexual relationships’ – along with the abandonment of his family – could go a long way to explaining his famous Black Paintings.

Painted between 1819 and 1823 as murals at the Quinta del Sordo villa, which he shared towards the end of his life with his housekeeper/companion Leocadia Weiss in Carabanchel, Madrid, they are among the most impactful artworks ever created.

So who knew about this previously unknown side of one of Spain’s most famous painters?

Not many people, as it turns out, though Manuela Mena, who recently retired from her position as head of conservation for Goya at the Prado, came forward with a theory that he was gay last year.

She suggested the idea after spending five years of research based on the artist’s 1775-1799 correspondence with his childhood friend, Martín Zapater, which she maintains was unusually intimate.

Goya was not keen on the pen in general, she argued, so these 147 letters provide a unique insight into his life, though the content is largely considered mundane.

Mostly staying on the subject of hunting, music and food, they are however, far from cast iron evidence that he was gay, insists British historian and Goya expert Stephen Drake-Jones.

“I think the claims are absurd,” says the President of Madrid’s Wellington Society, who lectured on Goya at the University of Syracuse, Madrid, for six years and has just published Letters Home from the Basque Country.

“In all the years I have studied Goya, it has never once been mentioned,” he told the Olive Press.

Born into a lower-middle class family in the small Aragonese town of Fuendetodos, Francesco de Goya y Lucientes moved with his aspiring parents and three older siblings to Zaragoza at the age of three, where he would subsequently hang out on the dusty streets with the other children and forge a lifelong friendship with Zapater.

At the age of 14, his artistic abilities were spotted by a priest from a picture he had done of a pig on a wall.

But though the boys’ lives would then take different directions, with Goya studying art in the city under Baroque painter Jose Luzan, they remained close.

Goya had a chequered start to his career as an artist.

While he worked under Luzan, he was allegedly also the ring leader of a local gang and when he returned to Luzan’s studio with a knife in his back, he was urged by his mentor to leave Zaragoza and apply to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, in Madrid.

His application was not successful though, and he went to Italy for several years instead.

But he finally found favour with Charles III in the Spanish capital, thanks to fellow artist and mentor Francisco Bayeu, and became chief painter at court.

“My Martín,” he wrote to his friend. “I’m now the King’s Painter on 15 reales a year!”

Goya had by then married Bayeu’s sister Josefa. He was 27 when they tied the knot and, though there are few details of the relationship, we do know that numerous pregnancies led to only one of their children surviving past infancy, which must have been heartbreaking.

But, according to historian Drake-Jones, Goya in no sense abandoned his wife or his son, as actor Irons has claimed. In fact, her death in 1812 could have contributed to his descent into depression.

But 17 years after his wedding, his letters to Zapater are certainly more ambiguous.

In November, 1790, one missive is emblazoned with a heart laced with engorged arteries instead of the mandatory cross which the Inquisition demanded.

In the same month, another is adorned with a sketch of a penis.

And in December that same year, he writes, “Yes, yes, you bring my senses to life with your discreet and friendly productions, with your portrait in front of me it seems I have the sweetness of being with you, oh, how could my soul believe that friendship could reach these heights.”

While Goya’s exact closeness with Zapater (and he painted two portraits of his friend) may still be shrouded in mystery it was without a doubt a close relationship.

But Goya also painted his wife twice, as well as the Duchess of Alba, whom he was rumoured to have seduced, though another biographer Robert Hughes believes their relationship only ever amounted to a close friendship.

A woman of her age and lineage would not have fallen for the charms of a man 20 years her senior who was far from her social equal, Hughes maintains.

He added that his celebrated painting ‘Maja Desnuda’, on which much of the speculation is based, is not the Duchess at all.

Whether or not Goya had homosexual feelings towards Zapater is open to interpretation as is almost everything about Goya, and the Prado Museum remains non-committal on the issue.

“This ‘perception’ is personal to Manuel Mena,” a spokeswoman told the Olive Press.

With regard to Goya dabbling in Satanism, Drake-Jones is unequivocal.

His paintings may have at times been ghoulish and disturbing with themes of insanity (Yard with Lunatics), nakedness, witchcraft (Witches’ Sabbath) and religion running through them, but he maintains: “It would have been too dangerous for Goya to be involved in devil worship.”

He continues: “He was a court painter. Everybody knew him and he could have lost his job or his life. He could have been garrotted – a form of strangulation, though at least you’re sitting down!

“You were allowed to paint mythology and in his black period you have Saturn Devouring His Son, but that was the norm.”

According to Drake Jones, there is no mystery about Goya’s black period either.

“He had gone stone deaf,” he says, referring to the illness that left Goya with a constant ringing in his ears at the age of 47.

“The absolutist king Ferdinand VII comes back to the throne and plunges Spain into darkness and persecutes him. And he shuts himself away.”

As Jeremy Irons says in his documentary tour, Painters and Kings of the Prado, ‘Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life’, allowing us the freedom perhaps to interpret it as we choose.

READ MORE:

PICASSO: Spain’s most famous artist was a rogue when it came to love

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.