Let’s get this straight. Everybody has the right to die. Full stop, put the kettle on, I might as well end the argument here. But I can’t. Because like most things in life, death is not that simple. While in a sense, everybody already has the right to die, is that enough reason to give the State’s formal approval to it?

Assisted dying is now prohibited in Spain following a landmark bill approved by parliament on Wednesday, March 18th. Under the new legislation, which will take effect in June, anyone with ‘serious and incurable’ diseases or a condition which is ‘chronic or incapacitating’ and causing ‘intolerable suffering’ can request help to die.

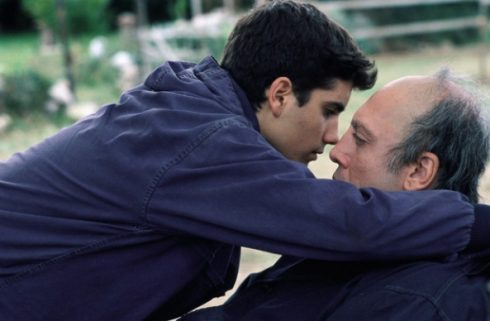

Euthanasia, though sad and traumatic, is also a subject most of us are familiar with. We study the ethics of it in our schools and read about the campaigners seeking to change the law in our newspapers – we even watch euthanasia storylines unfold on our favourite shows and movies. From Hayley Cropper’s devastating battle with pancreatic cancer in Coronation St to Javier Barden’s moving portrayal of a tetraplegic man in the 2005 Oscar winning movie The Sea Inside – euthanasia is never far from our minds or our headlines.

Perhaps it is thanks to these touching dramatisations that most of us are in favour of euthanasia. Research show that the majority of the Spanish public agree that euthanasia should be legalised – 90% of the public support the choice of assisted dying for terminally ill adults according to a 2019 survey.

But while Hollywood continues to shine the spotlight on tragic journeys and individual suffering, they do not provide answers to the questions that continue trouble us all. Despite parliament’s recent approval of the new euthanasia bill, the topic remains a tricky subject.

For example, when Belgium legalised the practice in 2002, the following year figures show that just 235 Belgians were euthanised. But since then the numbers have grown each year and now stand at around 1,400. Similarly, the Netherlands have seen the number of cases has doubled over the past decade. Euthanasia now accounts for a shocking 1 in 30 deaths. Most concerning of all is that the country had extended euthanasia laws to encompass an ever-widening group. The laws no longer just include people with terminal illnesses but definitions of unbearable suffering now extend to mental and emotional distress.

Psychiatric patients are now among those helped to die by Dutch physicians – the danger here is that legalising euthanasia creates an environment where assisted death is not the exception, but the norm. Now the law is in place in Spain, will definitions be extended? Will interpretations be distorted? Will safeguards will be slashed – putting the most vulnerable members of our society at risk?

READ ALSO:

The movement’s language of personal choice can make its cause seem attractive – but how can we be certain that we are acting on the desires of the person that is suffering? How can we be sure that an unwell individual has not been coerced or manipulated into thinking that death is the only option? And why are we not spending our time and resources persuading them that life is worth living? It’s no secret that Spain is in the depths of a care crisis and there is a real danger that euthanasia would open the floodgates; allowing assisted death to not only be seen as an acceptable option but also a quick and cheap solution.

Tellingly, an American survey found that support for legalisation is highest among people aged 18 to 44, and lowest among the over-70s. It’s easy to assume when you are young and healthy that death is less frightening than pain. We might even support assisted suicide out of a sense of misplaced sympathy. But until we have endured ill health or old age, who are we to say that a life lived in pain is not a life worth living?

That’s not to say the new bill doesn’t include strict criteria. The patient must be a Spanish national or a legal resident and be “fully aware and conscious” when they make the request, which must be submitted twice in writing, 15 days apart.

The request can be rejected if it is believed the requirements have not been met; it must be approved by a second medic and by an evaluation body.

Any healthcare professional could withdraw on grounds of “conscience” from taking part in the procedure that would be available through Spain’s national health service.

And that’s important. Doctors should of course have the final say, their job after all is to always do what is right by the patient. But doctors cannot identify who is being coerced by subtle influence or through unaddressed concerns. Consent to euthanasia cannot always be guaranteed. Until it can, we should be putting our efforts into better palliative care and suicide prevention – not asking our doctors to assist in suicides. When a healthy or young person tells us they want to take their life, we see it as a tragedy and do everything we can to help support and prevent the loss of life. Shouldn’t we extend the same courtesy to everyone, no matter their age or their illness.

READ ALSO:

Click here to read more Opinion News from The Olive Press.