Huawei’s TECH4ALL initiative aims to ensure nobody is left behind in the digital world by encouraging digital inclusion programmes and empowering technology adoption globally. The project is similar to some of the work happening within academia across Europe, where research projects are focused on harnessing technology for societal good.

Professor van Ginneken, Professor of Medical Image Analysis at Radboud University Medical Centre in The Netherlands, is introducing digitized healthcare solutions to developing countries and believes that in ten years’ time, all hospital pathology departments will be digitized. He spoke to Huawei about the work he is doing…

Professor van Ginneken, Professor of Medical Image Analysis at Radboud University Medical Centre in The Netherlands, is introducing digitized healthcare solutions to developing countries and believes that in ten years’ time, all hospital pathology departments will be digitized. He spoke to Huawei about the work he is doing…

When did your work in medical imaging begin?

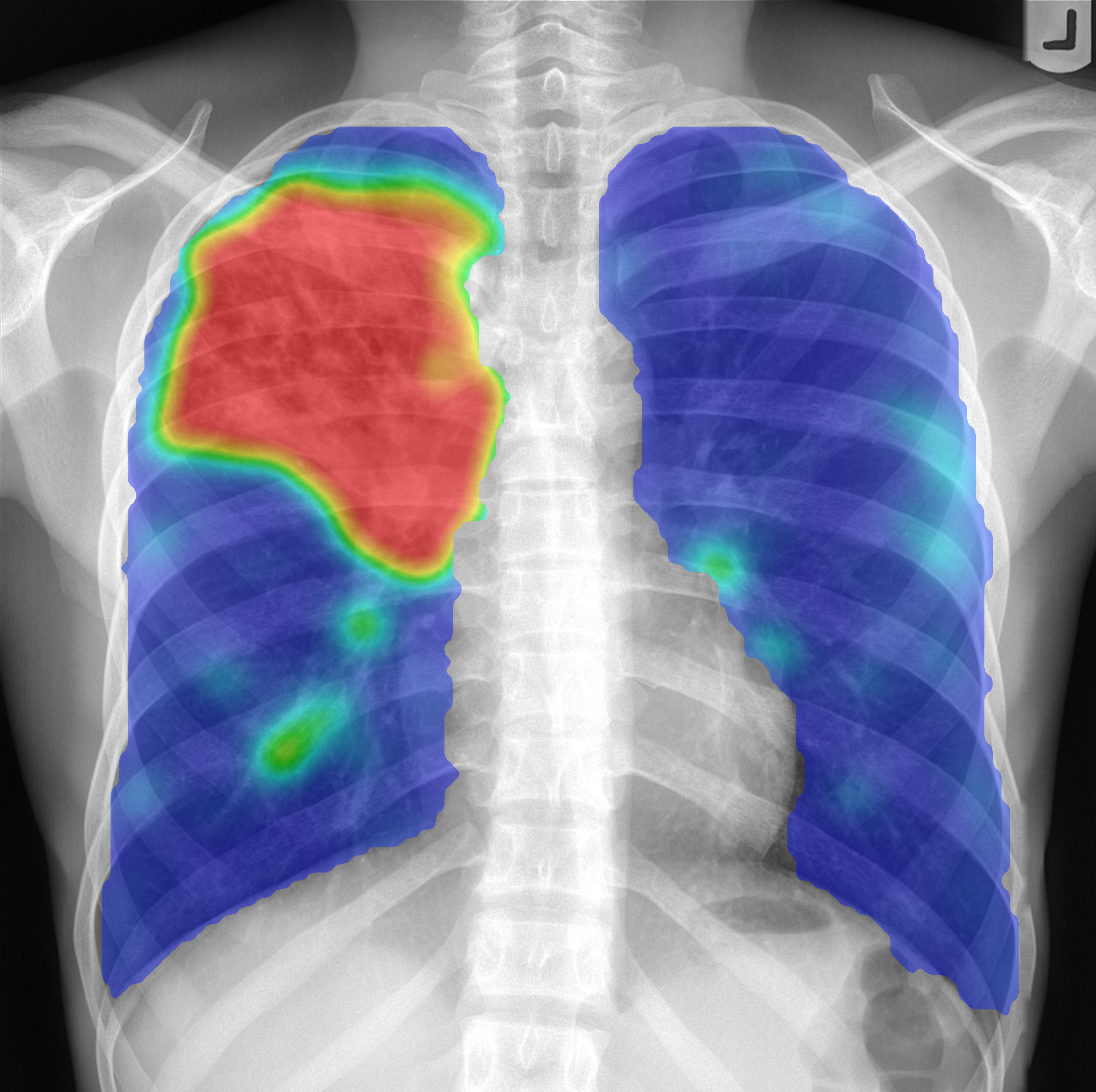

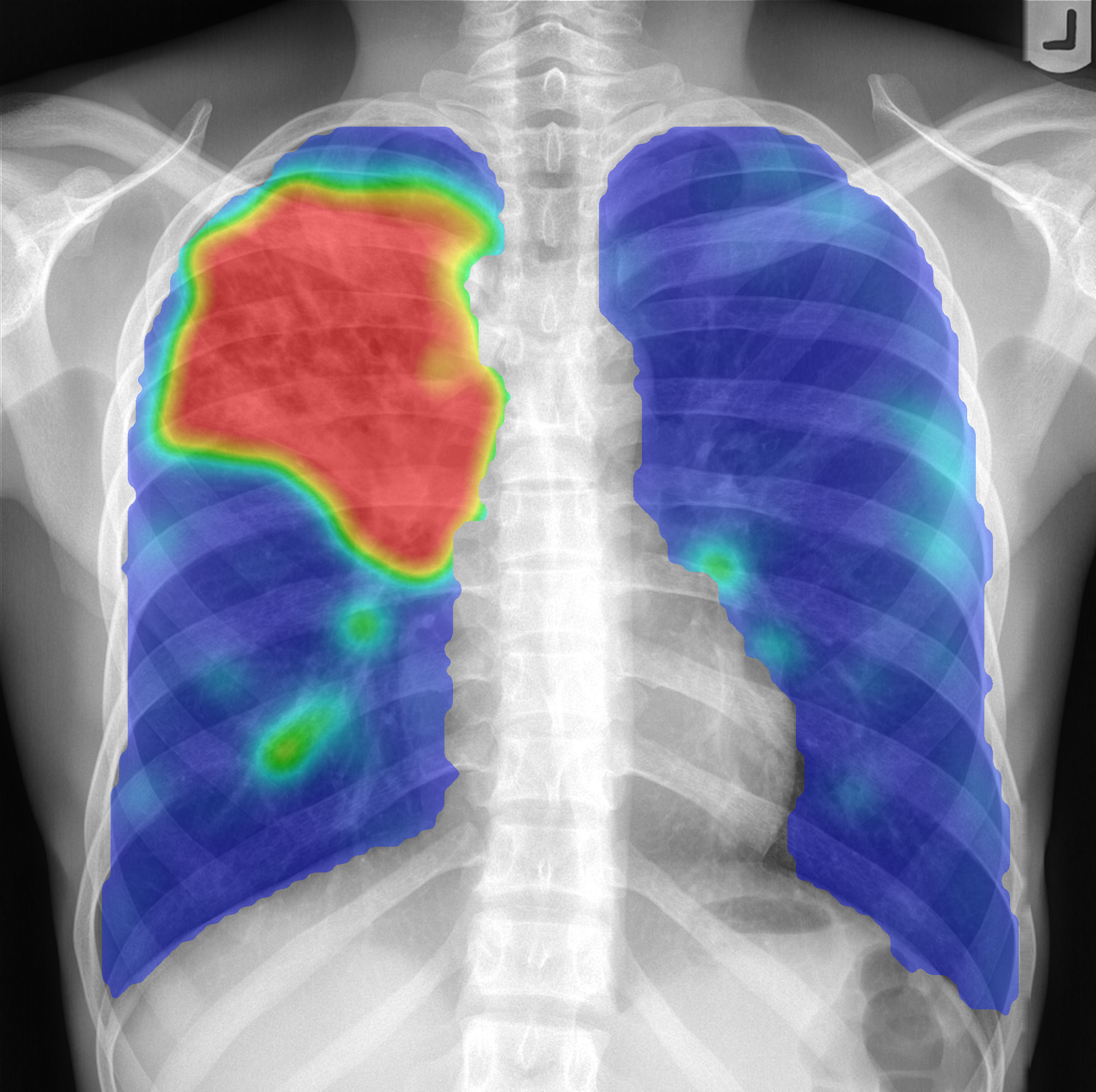

I studied physics and completed a PhD in medical image analysis in 1996, developing computer programs that analyse chest x-rays using artificial intelligence (AI). At the end of the 1990s we wanted to put digital chest x-ray units with AI software in countries where there was a lot of tuberculosis, because it accommodates faster, more widespread screening, without the need to develop images on film. However, digital x-ray equipment was too expensive at that time.

In 2012, deep learning broke through and made AI for medical images more popular. I moved to a university in the east of the Netherlands and set up a group of 70 researchers analysing medical images. Five years ago, we began working with pathology departments to digitize images. The trouble is, when stored for medical use, these very big images take up a lot of space. Departments are therefore deleting all their images after three months – so we can’t use them for deep learning. As storage systems become cheaper, we are closer to solving this. We will see all pathology departments digitized within the next ten years, I’m sure.

What has restricted hospital digitization up until now?

Healthcare is conservative. New solutions have to be proven in large trials, and there are many legacy processes.

There was a simulation study in Sweden using the latest mammography AI system. Researchers compared it to traditional care methods. They found the AI system worked as well as a hospital’s own radiologists and even outperformed some. So, they proposed to allow a large percentage of mammograms to be read only by the AI system. If it identified an issue, it would flag it with a consultant who would investigate.

The simulation showed this works, but it is not implemented. Instead, it is argued that the hospital should do a prospective trial. A trial easily costs around €10 million so they would need to find large funding. This trial would take years. I’m sure that by the time they have completed the trial, the AI software will have advanced so much that this prospectively validated technology will already be obsolete.

That’s the challenge we have. We need to validate systems before they can be used, but that takes time due to regulations, and in the meantime, these systems are rapidly improving.

Would this help the developing world?

AI is advantageous for the developing world because there are fewer legacy processes and less regulation. Look at Africa. They never had a landline infrastructure so went straight to mobile phones. The same can happen with digitization and implementing AI in healthcare.

Digitization will decentralise healthcare functions – making them accessible to more people in more places. We see this across African countries, where handheld imaging devices are being deployed; and in Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America, where first-of-its-kind tuberculosis screening programmes use mobile testing units, allowing professionals to target vulnerable demographics. In this respect, developing countries are leaders in adopting new medical technologies. At the same time as reducing set-up costs, they bring healthcare directly to the patient.

What is your company Thirona all about?

I set up Thirona with Eva van Rikxoort in 2014. Our vision is to close the gap between academic developments in medical image analysis and clinical usability needs. These must be bridged by creating products that include the latest technologies but are also intuitive for the user and aid medical specialists. Today we have 30 employees.

We also set up grand-challenge.org, a platform for end-to-end development of machine learning solutions in biomedical imaging. It enables anyone to add a challenge, for a network of AI and medical imaging experts and enthusiasts to solve. It allows groups from all over the world to collaborate on new AI solutions.

What does the future of global healthcare look like to you?

One with AI and digital technologies at the heart. Digitization will soon be across the hospital. Personal handheld technology will play a greater role; instead of stethoscopes, doctors will carry personal ultrasound devices. Deep learning systems are being developed to run on mobile phones so they can scan and analyse images instantly, giving doctors more control and patients more instant feedback.

We will see a global care model develop as geographical boundaries diminish. Rather than having every image analysed in the same hospital where it was taken, we can send images to the leading experts in that particular field, wherever they are. It makes for a more efficient system and one that delivers benefits to all, especially those in developing countries who gain a new level of access to healthcare. That’s the future I am working to create.

Professor van Ginneken and Huawei are continuing to collaborate, working together with technology for the benefit of health services. Huawei is also investigating how its own technology solutions can support Professor van Ginneken’s projects.

For more information about Thirona, visit https://thirona.eu/

Click here to read more Health News from The Olive Press.