By Laurence Crumbie

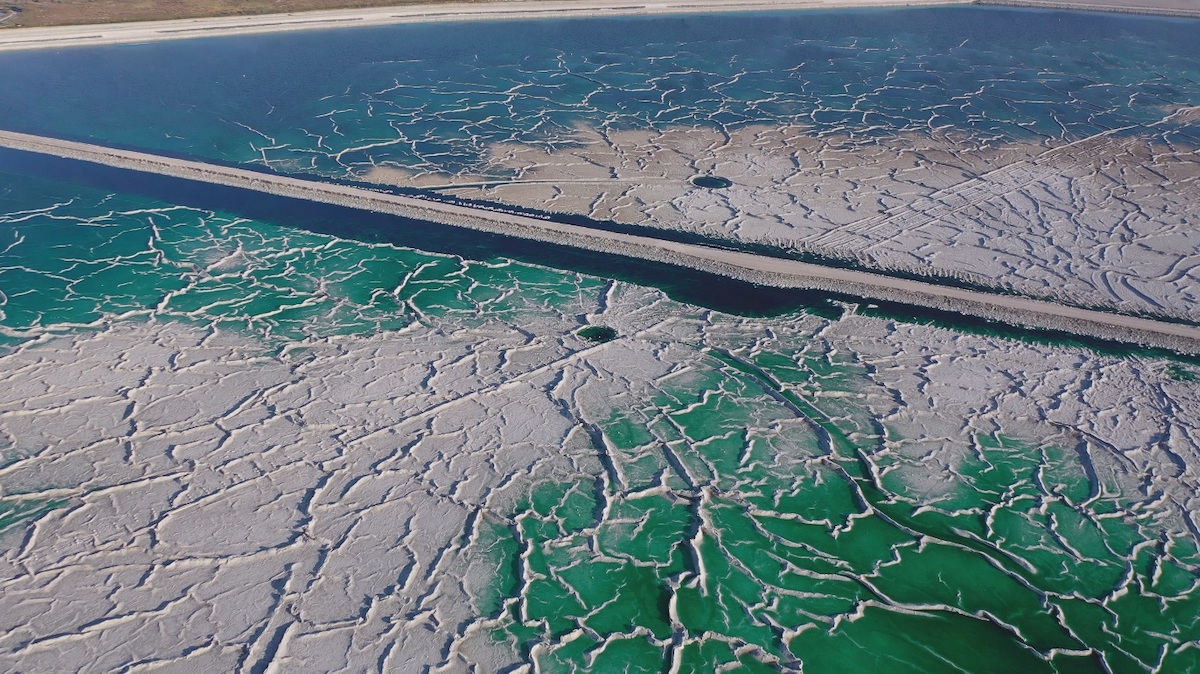

AT first glance, you might think a sci-fi writer had dreamed up this polar scenery of ice-like foam sheets atop a dazzling green sea.

Small natural pockets, akin in appearance to the breathing holes of Arctic seals, disrupt the venous white plains that extend over 1000 hectares. In the middle reside pools of deep emerald liquid and channels of the same colour criss-cross the surface, creating patterns in this surreal landscape.

The result is an area of unusual beauty – at least when viewed from above. The reality on the ground, however, is a different story. Born through careless dumping, these lakes of phosphogypsum and other dangerous substances are located only 500m from the urban centre of Huelva, Andalucia. They are the waste products of fertiliser production, a business which began in the region during the days of Franco, when environmental laws were lax.

For almost 30 years, fertiliser company Fertiberia produced 2.5 million tonnes of phosphogypsum annually, discharging 20% of it into the Odiel river estuary. Some of the lakes’ contents have seeped into the sea, drawn out by the tide. In response to an order from the National Court to prevent contamination, Fertiberia has proposed to cover the lakes in earth and clay. But not everyone is pleased with the plan.

‘It is a joke and they will leave a chemical bomb under the protection of the tides and climate change,’ said Julio Barea, head of a water campaign for Greenpeace.

Likewise, Aurelio Gonzalez Peris from Mesa de la Ría, an environmental group that has been critical of Fertiberia for years, said that the proposal threatens both the nearby marshes and the wellbeing of Huelvan residents.

Although a group of 19 scientists have said that burying the lakes would put them at the mercy of earthquakes, the plan has gained initial approval from the government. Now, the future of this toxic legacy lies in the hands of the Nuclear Safety Council and the Junta.