A COLD WAR MENTALITY was deeply entrenched on both sides when, on the cool winter night in 1966, a fully loaded American bomber flew some 31,000 feet in the air above the Spanish coast on nuclear patrol.

Out of nowhere it stuck a refuelling jet, shaking loose its four 1.5 megaton bombs with catastrophic effect.

One bomb fell five miles offshore, into the Mediterranean sea, and was later recovered two months later after a frenzied search. Another, equipped with a parachute, landed intact.

But two hit the ground at high speed, scattering three kilograms of highly radioactive plutonium 239 across the pastoral landscape.

It was one of the biggest nuclear accidents in history and Palomares – a tiny white tiled fishing village largely untouched since the Roman times – was devastated by the aftermath of the collision.

The two bombs wrecked the village – already a primitive place with no electricity or running water – leaving house-size craters on either side of the small town and a piece of the bomber plane lying blackened in the yard of the local school.

Thankful no one on the ground was killed but farmers lost their livelihoods overnight, waking up to see fine dust of plutonium over fields and fields of ripe red tomatoes.

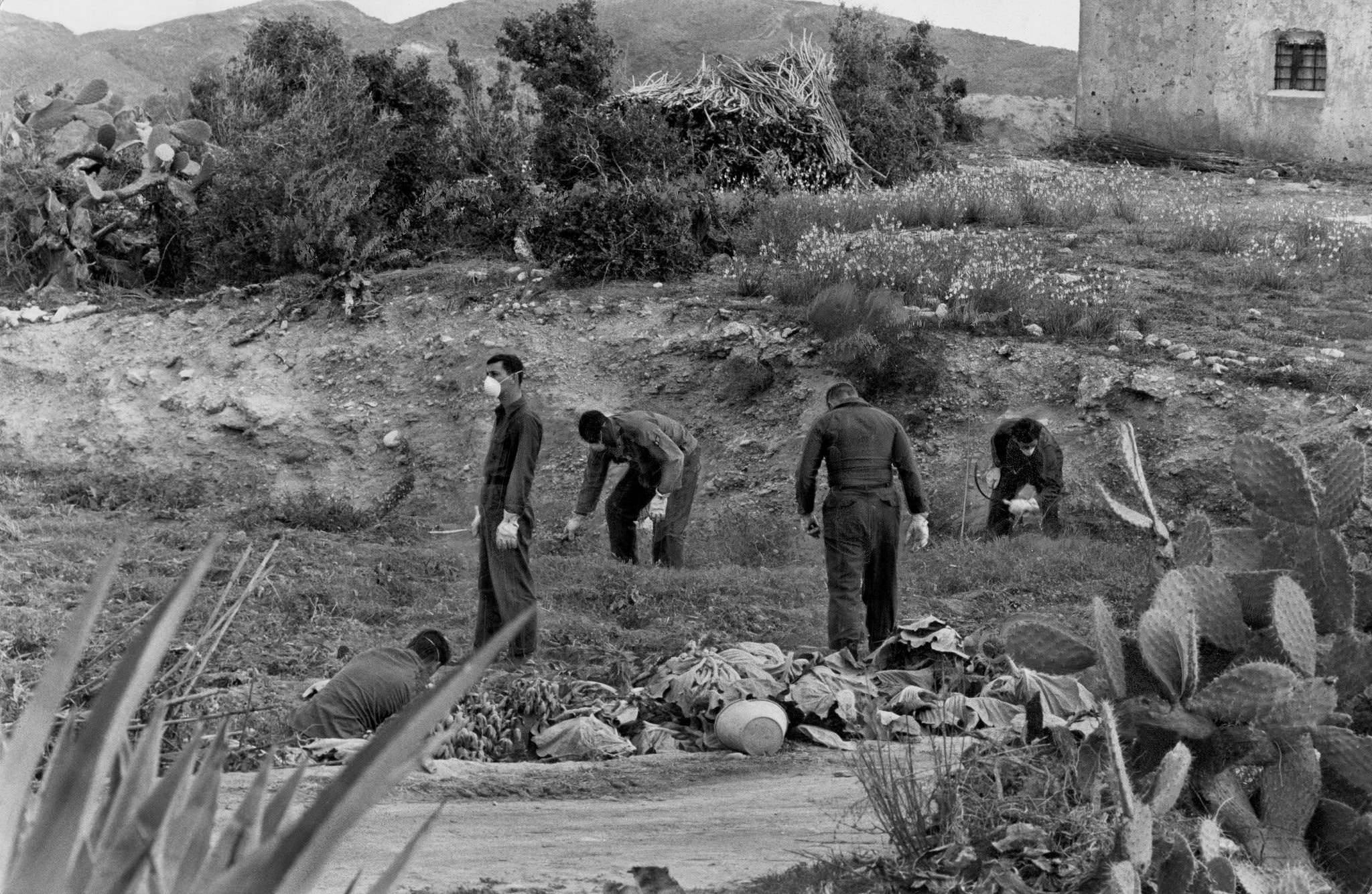

The day after the crash, busloads of troops started arriving from US bases, bringing radiation-detection equipment and hacking down contaminated fields of tomato vines with machetes.

The village was hastily blocked off, with both the American and Spanish government keen to downplay the incident. The US denied nuclear weapons or radiation were involved in the collision and it was a month before they admitted that one bomb, not two, had “cracked,” but had released only a “small amount of basically harmless radiation”.

But for years locals remained sceptical, advising children not to play near the site and visitors were warned not to eat the snails, a delicacy.

The same year the hydrogen bombs fell Franco’s Minister of Information and Tourism, a portly man named Manuel Fraga, made international news when he donned bathing trunks to go swimming with the US Ambassador, Angier Biddle Duke, off the beach at Palomares to demonstrate that the water was free from nuclear contamination.

Mr. Duke told reporters at the time, “If this is radioactivity, I love it.”

The high-profile splash worked, and for a while it seemed to assuage people’s fears. But back in the US, the servicemen sent to clean up the plutonium were developed various forms of cancer, blood disorders, heart and lung dysfunction and other sicknesses.

For 50 years, the Air Force maintained that there was no harmful radiation at the crash site and denied the troops disability benefits.

Instead they maintained, much like the portly Fraga in his swimming trucks, that the danger of contamination was minimal.

But evidence shared at the ongoing court case tells a different story.

The 1,600 servicemen were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation daily for weeks or months at a time, according to court documents filed by the Yale classmates.

The students had read about the case in the media, and got in touch with Victor Skaar, Air Force veteran, 83, that has a blood disorder and developed melanoma and prostate cancer, which were successfully treated. He believes his ailments were related to his service in Palomares and is currently in a class-action lawsuit seeking benefits for him and dozens of others who say they were exposed to radiation during the recovery and cleanup of the undetonated bombs and later became ill.

A lawyer for the VA defended the radiation exposure data this month and the three-judge panel is not expected to rule for weeks or months.

About a fifth of the plutonium spread in 1966 is estimated to still contaminate the area. After years of pressure, the United States agreed in 2015 to clean up the remaining plutonium, but there is no approved plan or timetable.

Click here to read more News from The Olive Press.