Words by Barnaby Bouchard

TO walk through the centre of Valencia today is to see the city at its least ‘Spanish’. Or so it would seem.

While one could fill a book delving into why painting ‘Spain’ as a single cultural entity can never end well for anyone, us expats who live here have all observed the difference in outlook that sets the people of our adopted homeland apart from those of the grey, drizzly climes from which we originate.

The Spanish differ from us in their in-built belief that it is their right, if not their duty, to have a good time.

We see it in their festivals. We see it in their cuisine. We see it in their music, their art, and their architecture. We see it in the way they say hello, the way they say goodbye, and in the hours of raucous, bravas-fuelled joy in between.

From their colourful buildings to their colourful language, from their thirst for dry humour to their thirst for dry wine.

Where else could they sell cigarettes for €4 a pack and still boast the highest life expectancy in Europe?

Where else would regional holidays see locals running through town chased by bulls (Navarra), burning a fifty-foot plaster sardine (Murcia), and letting toddlers run amok with what are, essentially, grenades (Valencia)?

Where else would take as its foundational piece of literature a novel about a senile knight who spends his days shouting at windmills?

The Spanish are a race from whom we can all learn much about contentment.

Not that any of this trademark positivity can be seen on a walk through Valencia today, of course.

Today, in every street, from the fashionable apartment blocks of Ruzafa to the Medellinian slopes of Burjassot, the silence deafens more than any Fallero’s firework.

The bars are shuttered, the parks empty, the squares positively funereal.

The only sound throughout most of the day will be the barking of a dog, the clatter of a pigeon taking flight, or the dull, distant hum of trains, arriving empty, leaving empty.

Occasionally one might see the odd flinty-eyed wino or clutch of confused German backpackers, but that’s all the life one can hope to see on the streets of one of Europe’s most effervescent cities.

The Las Fallas lights still hang across every street, but now serve only to heighten the sense of empty, echoing desolation.

It would seem, then, that the virus has put paid to these most admirable of Spanish qualities, to their easy-going amiability, their generous humour, their conviction that anything that can be fun should be fun.

And yet living through this lockdown has shown me that these very qualities have seldom been so evident, nor so timely.

My regret and frustration at this crisis is matched only by my gratitude at having been able to witness first-hand the unprecedented sense of community that has crystallised here in Valencia.

People here are, as we all are, confused and frustrated.

They are no more immune to this virus, nor to any of the social or economic issues it’s touched off, than anyone.

Indeed, as I write, Spain is among the worst-affected countries in the world, with over 3000 loved-ones already dead from the wretched virus.

I would never claim that people here suffer any less from pain, anxiety, loss, than any other human. Still less that what is happening here now is anything short of a catastrophe, the effects of which will leave an indelible mark for years to come.

Having said that, the sense of solidarity and support among Valencians (most of whom have no previous acquaintance with one another) has been nothing short of incredible.

Young people have been providing the elderly with their contact details, lest they feel isolated. Local bakeries have been serving free coffee to health workers.

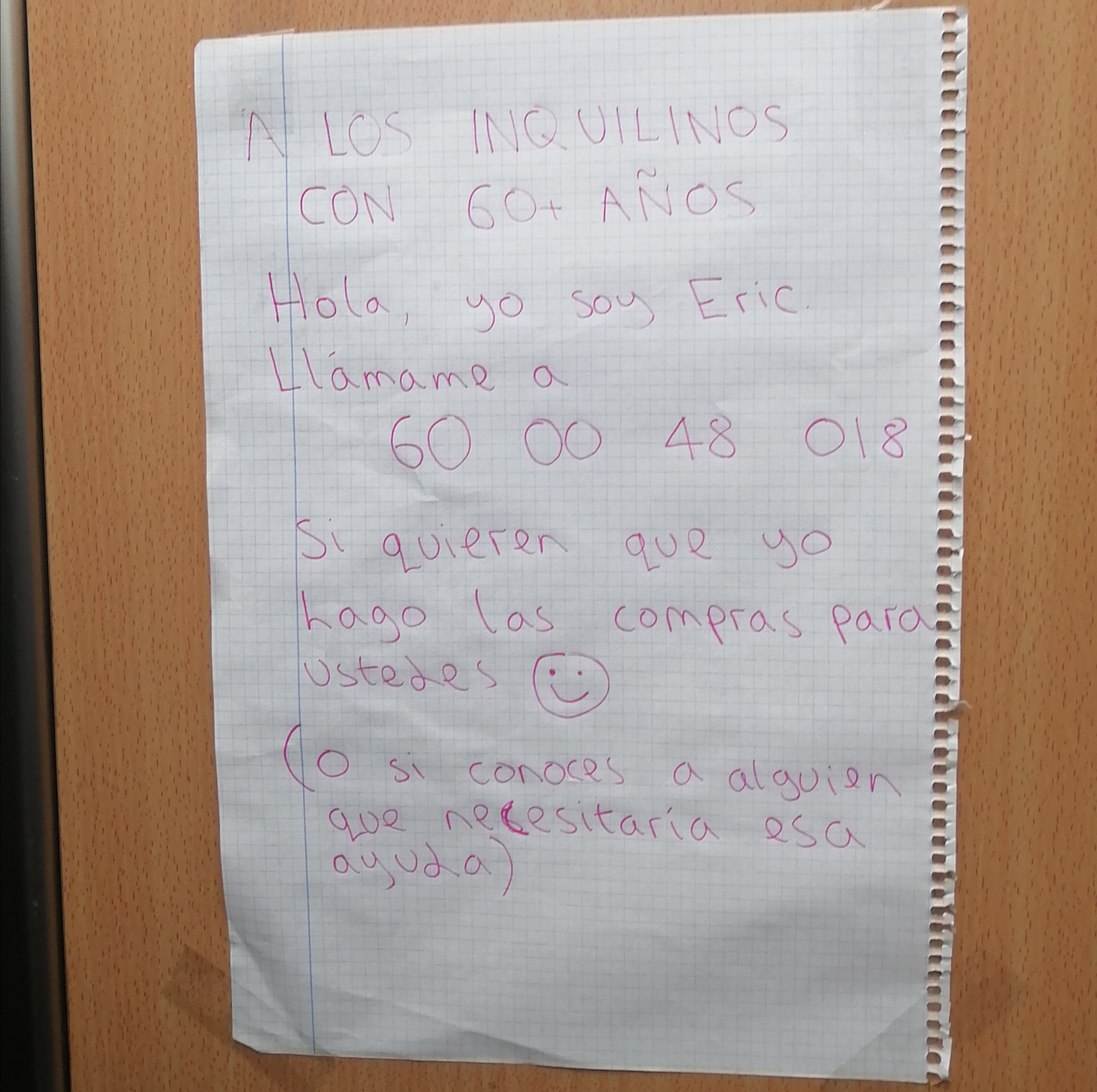

Just in my street, some neighbours have been providing nightly classical music concerts on their balcony. The facades of apartment buildings rustle with handwritten signs offering vulnerable residents help with their shopping.

Every day at twelve, the ‘city of a hundred bell towers’ is filled with a merry chorus of chimes, ringing out from the squat little churches to the stately cathedrals of El Carmen.

And, of course, at eight o’clock every evening, every Valencian goes out to their balcony to join the applause, cheering and music that ripples across the city. It is the most moving and heartening display of spontaneous human solidarity I have ever been lucky enough to see.

The Spaniards have taken to the internet to bring their acerbic wit to bear on a situation at which, at times, one can only laugh.

They have posted photos of rolls of toilet paper with bike locks around them. They have jokingly (one would hope) suggested avoiding shaking hands by reverting to the old dictatorship-era salute.

Refusing to allow the pandemic to divert attention from their shaky coalition government, they remark that President Sanchez’s vow to relentlessly oppose the virus means he will have entered a political pact with it by the weekend.

For the Spanish, the pandemic is, like all of life’s peaks and troughs, just another opportunity to laugh at themselves. They are consummately aware of what cannot be changed in life, and what can be.

The bars may be closed. The streets may be silent. The future may be uncertain. But Spain’s welcome has never been warmer.

This article puts its finger on the wonderful kindness and friendliness of the people of Valencia. In their city where I too am house bound. On the trips to buy food this 77 year old in a wheelchair only has to look up at a high shelf item in the supermarket before , at least three people ,rush up to ask if they can lift down anything for me from the higher shelves, bless them and I do I had already falen in love with the city and was here on a trial relocation which may go on and on, which is fine by me. and if I have to go through this virus scare I cant think of a better city and a nicer people to share it with..despite the underpopulated streets looking grim now, the slightest communication erupts with laughter and smiles; I had always admired Valencia’s stand against fascism in the civil War but now, as with the author of this article, I can begin to sense why and how they where and, hopefuly will always remain, unbroken and loving and shareing the joys of life; Thank you Valencia I am proud to share this crisis with you

As a fellow citizen of Valencia, this article perfectly and eloquently sums up life at the moment. Such an wonderful account of current life in an amazing city. Would absolutely love to hear more as the situation progresses. Can’t wait to hear this writers next piece!

I’ve lived in Valencia for a while, and I have to say this reflects the situation here perfectly. I’ve just forwarded the article to my family at home in Norway as way of explaining the situation over here. Thanks to the writer for articulating the current life here.

The history and culture of both the city and it’s inhabitants come alive in these words, and shows us exactly why the Spanish are so beloved. For an ex-pat to pick up so clearly the strength of the spirit of Valencia, and to embrace and be embraced by it’s people shows a sharp eye, and I too look forward to his next special despatch.