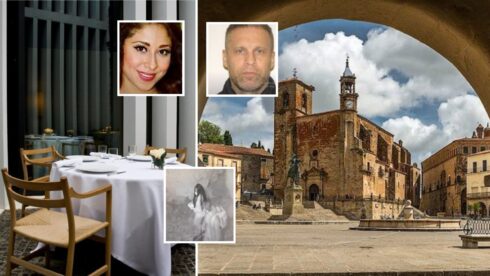

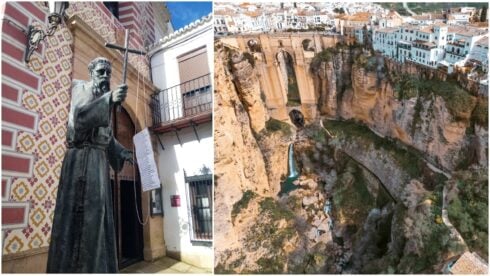

TWO hours before midnight, the whitewashed walls and polished cobblestones of Ronda’s Barrio de San Francisco are momentarily painted an olive oil gold.

We follow the creeping sunrays down a callejon on Calle de Angelita Aparicio, the slap of our sandals the only sound in this corner of the cloistered mountain town.

At the end of the dipping alleyway we come to a plot of well-tended land where Jose Luis, a Rondeño with salt-and-pepper hair, waves us over.

Crouching down, he tells us his allotment is ‘just a hobby,’ and, chuckling at our fascination, hands over a zucchini the size of his forearm.

‘A gift,’ he says.

Shortly after, he adds a cucumber to the mix, clumps of dirt still clinging to the knobby skin.

For many, travelling is a desperate race to hit the top attractions before the sun sets. Itineraries in hand, they eat quickly, walk fast, ticking the sights off their checklists like chores.

Each day is swallowed before it can be chewed.

But for others, the act of travel is less planned. Days are spent wandering. A 20-minute walk could take an hour.

Detours are welcomed, and locals become the best of guides.

Slowness, as a concept, began in 1986 with the slow food revolution. After the first McDonald’s opened in Italy on Rome’s Plaza de Spagna, thousands assembled to protest.

Then-journalist Carlo Petrini made a name for himself by passing out plates of traditional Italian penne pasta to the protestors, according to TIME Magazine.

Three years later, Petrini found himself at the forefront of what is now known as the Slow Food Movement, an international organisation dedicated to the preservation of local food and the traditional lifestyle.

With tapas and sobremesa among the national pastimes, Andalucia is ideal for this kind of unstructured exploration.

And one town in particular has made Petrini’s slow living principles its mantra.

Ronda, surrounded by the Serrania de Ronda and punctuated by craggy outcroppings, has managed to maintain agricultural traditions dating back to the Reconquista.

If, from a distance, the town does not look very alive it is because residents are probably ensconced in one of the many plazas.

Retirees in Panama hats shuffle around in groups of three, chatting over drinks.

Families gather for al fresco dining, their kids playing until late evening.

There is no need for security cameras, as all the terraces are equipped with observant abuelas.

In a corner of one of Ronda’s winding streets, Entrelenguas invites both transient visitors and settled expats to learn more about Spanish language, culture, and tourism.

Mar Rodriguez, Javier Criado, and Alejandro Montesinos — a trio of Rondeño specialists — founded this cross-cultural hub in 2014 to provide a different approach to tourism in their hometown.

Espousing the slow philosophy, at one end of this hip locale is a brightly-lit classroom, at the other an array of artisan products, from wine to fans.

The relaxed vibe is completed with a mosaic-encrusted bar, an indoor swing, a back terrace with picture postcard views and the friendly presence of Pongo, the dalmatian.

In its five years, Entrelenguas has formed several partnerships offering an authentic taste of life in Ronda.

Flamenco classes, leather workshops, organic farming and free hikes are among the immersive Spanish experiences on offer.

According to Montesinos, ‘the goal of these cultural events is to meet other people from Ronda’ which, he added, ‘is what many people who pass through are most looking for.’

Classes, leather workshops, organic farming and free hikes are among the immersive Spanish experiences on offer.

According to Montesinos, ‘the goal of these cultural events is to meet other people from Ronda’ which, he added, ‘is what many people who pass through are most looking for.’

For British retirees John and Annie, Spanish classes at Entrelenguas are key to helping them become Spanish citizens. They have been taking classes for the past three months and are proponents of the centre’s novel approach.

“There’s no way you can understand the culture of a place with ordinary tourism. You have to get under the skin of the place,” said Annie. “We’ve been in Ronda for 12 years now, and we’re still discovering new things.”

“We came with the intention of assimilating into the culture,” John added.

Entrelenguas actively works to protect that cultural authenticity and stave off the influx of mass tourism.

“Many places attract tourists by making up products. These places aren’t real, and they aren’t being honest with tourists,” said Rodriguez.

As a native who doesn’t dance flamenco or condone bullfighting, she’s also keen to show other sides of Spain not covered in glossy travel brochures.

“We know the local produce, the local wines. Those other places are contributing to the clichés of Spain,” she added.

However, for the traveller pressed for time, it isn’t always easy to differentiate between the manufactured and the authentic.

It was surprising to learn that the ‘paella individual’ commonly advertised in restaurants was a phenomenon invented for the checklist traveller; the overpriced dish is far from the family ritual of sharing a cauldron-sized paella on a Sunday.

To guide travellers away from the trite, Entrelenguas offers a map highlighting places that have been vetted for authenticity.

Distinguishable by an ‘Experience Local’ sign, these shops provide the best seasonal goods. By sourcing their products entirely from surrounding farms, they also contribute to the town’s sustainable development.

In the old town, La Tienda de Trinidad is all you expect from a traditional venta: an impressive line-up of jamon iberico hung from the ceiling, and an assortment of chorizo, goat cheeses, wines and beers from which to sample the full Andalucian experience.

Miguel, the owner, recommends visiting the bakery down the street, Antonio’s Panaderia Alba, to pick up some fresh bread first.

Slicing it in two, he expertly drapes several slices of jamon on top and drenches them in olive oil. This classic bocadillo is the perfect accompaniment to a stroll through the town.

Across the Puente Nuevo, past the camera-happy sightseers, sits El Lechuguita, a bar offering over 80 different tapas at less than a euro each.

Owned by three brothers, the unpretentious decor and standing-only room does nothing to reel in unsuspecting tourists. And that is precisely its charm.

It’s a different story round the corner in Ronda’s bustling Plaza España, where McDonald’s is doing a brisk trade — a sight that would have made Petrini weep.

Our shoes skid along slippery Puente Viejo, worn smooth by centuries of travellers, both friendly and conquering.

The walk to the bus station under the sweltering sun is one we severely underestimated; carting our suitcase up the bridge was an almost Sisyphean task.

Earlier that morning, we carefully wrapped the zucchini and cucumber Jose Luis had so thoughtfully gifted us.

Sandwiched between a sun hat and a water bottle, the vegetables jostled around in our case during the journey back to the Costa del Sol.

Travel can be a dislocating experience in so many ways. But, tucking into our fresh ‘campo’ zucchini stir fry back home, it becomes obvious why it’s worth it.

Far more than the picturesque sights and Instagram opportunities, the human memory bank stores the best moments.

The faces of the people who gave you directions to places unlisted on maps. The kids who showed you shortcuts to the best views in town.

The simple kindness of a farmer.

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.