A HUSH descended on the tiny village of Zufre as the names were slowly read out.

It was November 4, 1937 and approaching dusk in the mountain settlement that sits inside the stunning Aracena Natural Park, in Huelva.

Most of the local villagers had just made their way back into the village from the nearby fields.

A total of 16 women were called out and each was asked to jump aboard a truck that was supposed to be en route to the nearby market town of Aracena.

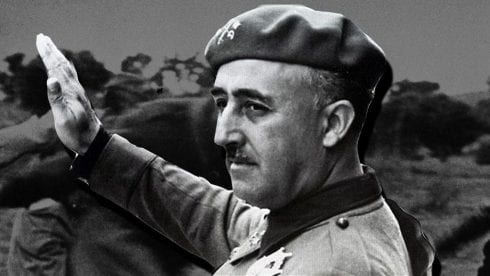

Ostensibly they were to make statements about the Civil War before the Nationalist authorities, who had secured the region for dictator Franco some months earlier.

However, nobody locally believed it and, according to witnesses, there was an eerie understanding that the fascist soldiers on the truck had other plans for their captives.

Zufre, after all, had been a staunchly left-leaning Republican town on the outbreak of the war in 1936 and the local militiamen quickly captured 60 Nationalists soldiers as prisoners.

Franco had been furious and ordered an aerial bombing of the town, which quickly liberated his soldiers, with most of the locals fleeing into the nearby hills or ‘relocated’ to Badajoz.

The 16 mothers, daughters and grandmothers rounded up that day were never seen again.

That is until this month, when a mass grave is expected to be opened in the nearby village of Higuera de la Sierra.

It is the fifth unmarked mass burial site to be opened in Andalucia over the last few years and archaeologists are expecting to find the bodies of women, who were most likely tortured and raped before being killed.

“They were rounded up in 1937, when Franco’s forces made a concerted effort to find the locals who had deserted villages across Andalucia,” explains Cecilio Gordillo, the driving force behind the organisation Todos los Nombres.

For the last 13 years he has been investigating the fate of the ‘disappeared’ victims of the Civil War, a third of whom were buried in Andalucia.

“There was a wave of repression against the women who lived in Andalucia,” the former bus driver told the Olive Press.

“Western Andalucia is the only place in Spain where they have found graves filled exclusively with women and Zufre will be the fifth such grave, though it is suspected there may be a few men in there too.”

However, he warned: “At least two graves believed to have contained the remains of executed women were empty so you never know what you will find until they are opened.”

He, along with the CGT-A Andalucia Working Group for the Recovery of Social Historical Memory were given the go-ahead last year and it is still expected to go ahead from July 15, despite the new right-wing PP-Ciudadanos-Vox coalition proposing to cut the historical memory budget.

However the dig will be highly controversial and emotive, as they usually are.

“We are having a meeting this Thursday to discuss the exact timescale,” confirmed local Higuera archaeologist Jesus Roman, who is involved in the dig.

The move comes just weeks after the five judges in Madrid postponed moving the body of General Franco from Spain’s huge Valle de los Caidos memorial, which is meant to be for victims of both sides of the war.

It would be something of a disaster to not afford these women a decent proper burial, believes Gordillo.

He explained that most of the 16 women knew this was to be a one-way ticket, despite their innocence.

One of them, 62-year-old Alejandra Garzón Acemel, aka La Pistola, turned to embrace a friend, whose name was omitted, crying: “Carmen, my dear, we are not going to see each other again.”

Few of them were guilty of anything more than being members of the UGT socialist trade union with some of them having family members already jailed for being linked to it.

The wave of terror launched on the women of Andalucia however, was a strategy for hunting down their menfolk.

“They were trying to make them reveal the whereabouts of a brother or a husband,” adds Gordillo.

“Or they believed that by torturing and executing the women, the men would emerge from their hiding places in the sierra.”

As they trudged up the hill to Don Angel’s medical clinic, where the truck waited, some passed their husbands, while others gazed longingly at their children who had gathered as usual around the local fountain to play.

Apparently, on seeing their mothers’ hands tied and their faces streaked with tears, the children turned their heads away.

Though the truck set off in the direction of Aracena, it apparently drove only as far as Higuera de la Sierra, just 12 km down the road.

The centre of the town, which like Zufre had around 1,000 inhabitants, was generally lively in the evenings with children playing in the square and elderly men slamming down dominoes and cards.

But by 7pm when the truck drove in, the light was fading fast and many had already gone indoors, leaving few witnesses to the atrocity that ensued more than 80 years ago.

However, Rosario, one living witness, did recall the macabre scene.

“A truck stopped loaded with women in front of the bar at 7pm,” she explained in her testimony to the association. “Their cries were chilling. They were told to get down and they filed along the street that leads to the graveyard.

“It’s a short stretch; maybe some of them didn’t know where the street would take them, but others would have known. ‘In line, that way!’ their executioners shouted.

“The cries of those wretched souls could be heard across the whole town. It gave you goosebumps. The people of Higuera were terrified.

“The women who refused to climb down from the truck where dragged off it, with kicks and a bayonet. Some may have arrived almost dead.

“The offloading took place quickly and they shot them at the gate to the cemetery.

“The old iron gate, which has been painted hundreds of times since, is still marked by the impact of the bullets.

“They buried them in a very deep grave that was already open, where they had already thrown bodies of others they had executed. They buried them in layers.

“They scattered soil on the last bodies in, then added more bodies.”

Ironically today at the entrance to the cemetery there is a headstone in memory of Franco’s Civil Guards who lost their lives in the attack on their barracks by the militias in 1936.

Of the poor women who died, there is precisely nothing to remember them by.

The youngest of the women was 30, the oldest 62.

Only seven of the 16 gunned down by the firing squad were officially recorded as dead.

It would be another 42 years before the fate of the others was even registered.

“My father was just seven when they took his mother,” explains Josefa Salguero, the granddaughter of Carlota Garzón Núñez, who was just 47 at the time of her death.

“I live in America and hope I will soon be able to visit the grave where my grandmother is.”

Higuera de la Sierra’s Culture Councillor, Maria del Prado confirmed the town hall had conceded permission to look for the grave.

“We are not otherwise involved. But it is hoped that if the grave is found it will bring peace to the families,” she said.

Certainly, it will address a painful chapter in the history of both Higuera and Zufre, closing this historic chapter in the history of the area.

“People have been saying when we open the first mass grave, you’re going to start another Civil War,” says Gordillo.

“Well, a lot of these graves have already been opened and absolutely nothing has happened.”

He continues: “We have a Christian culture and burying bodies is a Christian ceremony is the right thing to do.”

Spain is said to be second only to Cambodia when it comes to ‘missing’ persons.

By July, Todos los Nombres will have 100,000 names of the estimated 114,000 on its website.

As Gordilla points out: “We send a special division of the Guardia Civil to search for bodies in Yugoslavia and Guatemala.

“We have budgets for archaeologists seeking Pharaohs in Egypt, but what about our own grandfathers? It is time to deal with this once and for all.”

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.