If there was ever a case of shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted, it perhaps couldn’t be more evident than with the recent spate of high profile suicides linked to reality tv programmes. It was recently announced that the Jeremy Kyle show was to be ended and all repeats removed from ITV.

Last night saw a brand new series of the reality tv programme, Love Island. This kind of show might pass the majority of us by if it wasn’t for the tragic deaths by suicide of two of its former cast members. Sophie Gradon was 32 years old and Mike Thalassitis 26 when they sadly died after appearing on the reality tv show.

So why the fascination with watching seemingly chaotic people at best and mentally unwell at worst, arguing shouting and screaming at one another in front of a live audience and baited by Kyle? What could possibly ‘entertain’ people every weekday for 15 years? What is the key to the longevity of such programmes which seek to humiliate and destroy some of society’s most vulnerable people? Whilst some of us might scoff at the type of programme that has been mainstream in society for so long, are we not all guilty of voyeurism by tv. Hold that thought, because is Jeremy Kyle any different from say, 24 Hours in A&E, 24 Hours In Police Custody, Big Brother, Love Island, I could go on. Because all these programmes are designed to ‘entertain’ us, the viewing public. Yet all of these have a common theme, we are witnessing people at their most vulnerable, we are watching as their plights are held up to us in a way that we might never be privy to as the general public.

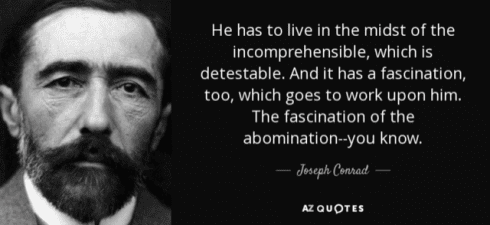

I am often reminded of the Joseph Conrad phrase which refers to humans as having a ‘fascination of the abomination’. Whilst this might seem to be quite a fancy way of referring to the human desire to look at things that are ‘abominable’ to them, let us think abut our own behaviour. How often have we driven towards a blue flashing light and slowed down, despite the fact we might witness some terrible accident whereby a stranger to us might be exposed, at their most vulnerable, after a serious collision. There is even a name for it, ‘rubber necking’. And as we approach the scene of an accident, even though it is on the opposite carriageway, we are greeted with a slow moving line of traffic for no reason other than human curiosity at the potential to see something ‘abominable’.

I tend to think that the very large majority of people are empathic to others and I truly believe that we are built to care for one another, particularly in times of crises. So why is this so at odds with the huge ratings that these reality tv shows get?

If we look at the history of reality tv we might find that it is interwoven into our culture and the culture of our times. The first reality tv show was in 1973 when a film crew followed a man called Lance Loud. He appeared in the US tv series, ‘An American Family’ when he came out as being gay to his family. He later went on to become a gay icon but died of AIDS in 2001. The culture of his time in the public eye was to be fearful of AIDS and to regard people with the HIV virus as being like lepers.

Could it be as simple as we are fascinated by something we find abominable and each culture and time in history views different people as being ‘abominable’? It might be very uncomfortable to think that we are perhaps not that far removed from our ancestors, who we might regard as barbaric as they flocked in their thousands for a family day out at the public gallows.

However, in my lifetime it was perfectly legal to go to a circus freak show and pay to look at people with physical deformities and mental health concerns. It was referred to as a ‘freak show’ and was perfectly acceptable until 1980.

Perhaps we find watching endless hours of reality tv as fascinating as our predecessors found public hangings, for example. Perhaps reality tv is the modern day equivalent of watching others in distress but from a safe and acceptable distance. Former reality tv host, Trisha Goddard gave an interview recently to a newspaper where she argued that if reality television producers ‘rule out people with mental health problems then you’d get nobody on TV’ (the guardian.com). Perhaps therein lies the sad fact that we are still fascinated by the other, people who are ‘different’ to the norm. As we evolve we appear to find new and acceptable ways to turn human suffering into entertainment.

Below, a clip from Channel 4’s Dispatches. A woman who worked on the Jeremy Kyle show talks about the concept of ‘talking up’ guests so that they create conflict.

Click here to read more News from The Olive Press.