HISTORY is written by the victors. But no victor is immortal and no victory permanent. With the inauguration of every new victor, the preservation- or rectification- of history begins anew.

However, for almost one century, Spain has wrestled with remnants of the Spanish Civil War that still pervade the entire nation and its seemingly benign Catholic monuments in particular.

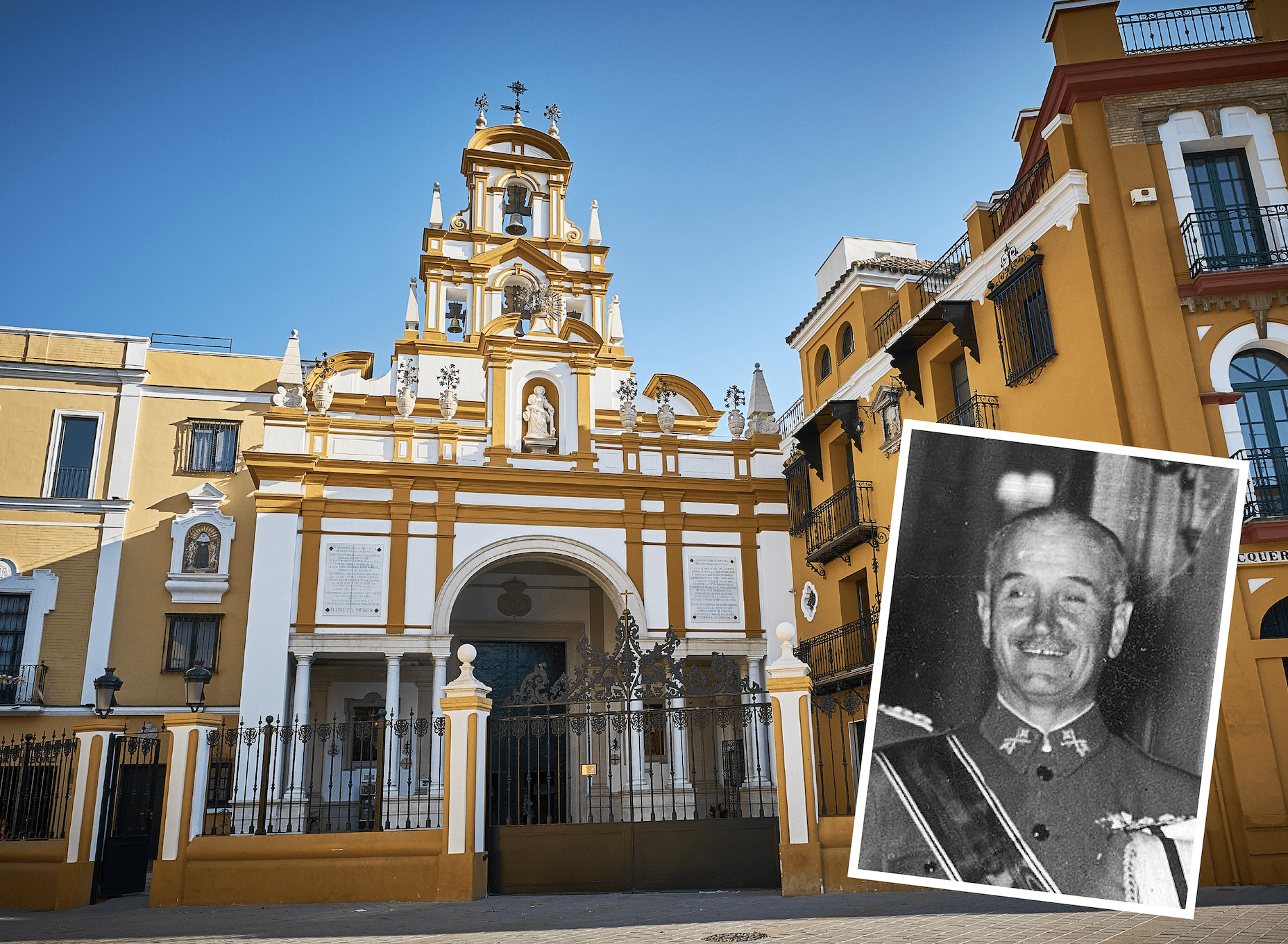

Sevilla is famous for its ornate royal palace and Catholic cathedral. Yet, both these iconic sites and the grand stone walls that surround parts of the city belie the atrocities committed there. Following the Civil War, more than 5,000 civilians were executed at the city walls by a military commander whose tomb now lies in the Basílica de la Macarena, just a few steps away from those city’s walls.

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano was a general loyal to Francisco Franco, the fascist dictator who ruled Spain for nearly four decades after his victory in the civil war. Queipo is single-handedly responsible for the execution of more than 50,000 civilians in Sevilla during the war.

I don’t know what I expected as I walked into the basilica. A group of visitors huddled around his plaque paying tribute? Pointing fingers at the deceased? I’m not sure, but I do know that I did not expect the complete ambivalence and negligence of the two rectangular plaques that greet you as soon as you walk in the cathedral.

People are so immediately enraptured by the burnished gold statues, dimly-lit atmosphere and ornate decorations of the cathedral that no one gives Queipo’s name a second glance. Perhaps this is what the ‘Pact of Forgetting’ looks like in action.

Following the death of Franco and the downfall of his dictatorship in 1975, leading political parties agreed on a tacit policy of Pacto del Olvido (Pact of Forgetting). The agreement silenced discussions about the horrific civil war and its legacy. It embodied fears of reopening old wounds and repeating the past. Hence, the atrocities committed by Queipo and others have long gone unaddressed.

Salvador Cardús, Professor of Sociology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a leading researcher in Spanish culture and religion, describes the pact as an ‘erasure of memory’ and ‘a collective amnesia’.

A move for national reconciliation attempted to bury the violence and brutality that marked the era of Francoism. It was a masterful act of creating nothing out of something, allowing Spain to seemingly avoid this painful subject for decades. But whether the memories are truly forgotten is questionable.

‘Memories of the war were not so much forgotten as ‘disremembered’,’ writes Madeleine Davis, Senior Lecturer of Politics at the Queen Mary University of London.

For the past century, the pact was kept despite a few largely unsuccessful attempts to overturn it. Although La Ley de Memoria Histórica (Law of Historic Memory) was passed in 2007 during the term of the previous Socialist prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, its enforcement was promptly halted when Mariano Rajoy’s conservative Populist party regained power in 2011.

The law had called for full state cooperation for families hoping to move bodies of relatives killed during the civil war from mass graves, as well as the removal of all remaining monuments of Franco. Both measures never came to fruition.

Now, with the appointment of socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez this June, possibilities for the exhumation of Franco and his military subordinates, including Quiepo, from the Valley of the Fallen have come back into the spotlight.

Andalucia has been in the forefront of this rekindled movement. Last year it passed La Ley andaluza de Memoria Histórica y Democrática” (Law of Historical and Democratic Memory) which bans all ‘elements in opposition to democratic memory’ on private properties ‘under public projection’.

The Basilíca de la Macarena, a private property belonging to the Brotherhood of the Macarena, is subject to this law. However the exhumation of Queipo from the basilica ultimately lies in the hands of the Brotherhood, which has been lukewarm about doing so. Earlier this year, José Antonio Fernandez, the head of the Brotherhood, recognised Queipo as ‘a protector of the movement of the Catholic Church’, noting his contribution in building the basilíca and criticising politicians for attempting to ‘open all this’.

But only last week, Fernandez confirmed to El Pais that he will propose the removal of Queipo’s body to the governing board of the Brotherhood. “The law speaks and the brotherhood abides,” he said. The day after his statement, the Brotherhood clarified that it ‘has not made any decision or reached an agreement’ on the matter, indicating a potential time haul before any action is taken.

Despite the Brotherhood’s reluctance, the Andalucian government has shown robust support for its new law and remains optimistic that Queipo’s remains will be removed from public display. “It’s only a matter of time,” said the vice-president of the Junta.

However, the emotional complexity of the issue far exceeds the legal complications. Just as left- and right-leaning politicians remain sharply divided on the treatment of civil war memorabilia, stark divisions still exist amongst the people of Spain: those who want to bury history, perhaps to avoid the pain; those who want to unearth it, perhaps to see justice for the pain; and even those who to this day celebrate Franco’s legacies.

For now, individuals who wish to address and rectify history seem to have the upper hand. Last week, premier Sánchez announced that the decision to exhume Franco is firm. “The wounds have been open for too many years, and the time has come to close them. Our democracy will stand as symbols that unite citizens,” he said.

Whether the fate of the bodies of Queipo and Franco would reopen or heal old wounds is a question that may never be answered with certainty, even after everything has played out. A city so visibly imbued with silent history, Sevilla has and continues to play host to an uncanny hide-and-seek between history, truth and pain.