WHAT did the British ever do for Andalucia? Like Monty Python’s Down with the Romans sketch, the answer is – actually quite a lot.

British entrepreneurs, explorers, writers, artists, politicians and even kings have been fascinated with the region for centuries and left their mark in a generally very good way.

They fought wars for the locals, built railways, wrote poetry to its cities, introduced sherry and laid the foundations for tourism itself, as the Olive Press explains.

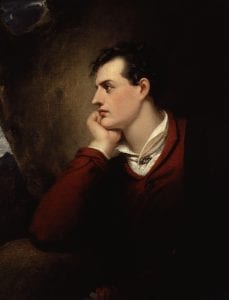

Lord Byron

Lord Byron

An 1809 graduate from Cambridge, celebrated poet Lord Byron had no plans to visit Andalucia during his gap year trip to Portugal and Greece. But after his French hero Napoleon Bonaparte began military campaigns in the country, the scribe found it necessary to travel through the region and was smitten by Sevilla and Cordoba. The result was his famous poem about the two cities, Childe Harold, in which he changed his allegiance to Bonaparte for the Spanish. The women of Cadiz also enchanted him, evident in some of his other works, and he is said to have influenced countless Spanish poets, leaving his mark on a region he originally intended skipping.

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward wasn’t just Queen Victoria’s dad. He was also known as the ‘Father of the Canadian Crown’ for sustaining Britain’s authority in Canada. History also suggests he fathered a few bastards in his time, some of which was spent as Governor of Gibraltar. While ruling the Rock from 1802-1820, there were rumours he kept a mistress or two outside the enclave in an Andalucian farmhouse (supposedly in Ronda) and, although details are sparse, he had at least three others while in England.

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli

From 1830 – 1832, two-term Prime Minister Disraeli took a break from politics to do some travelling and became Andalucia’s first unofficial PR man. In particular, he was impressed by Sevilla and Cadiz, and wrote of seeing a ‘Figaro in every street and Rosina in every balcony’, in reference to the characters from Rossini’s Barber of Seville. He was also complementary of Gibraltar, describing it as ‘a wonderful place, with a population infinitely diversified’.

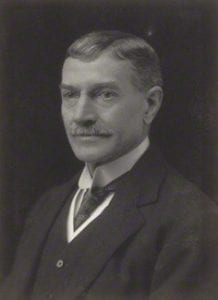

Sir Alexander Henderson

Scottish financier Sir Alexander Henderson played an influential part in founding the Algeciras Gibraltar Railway Company in 1891, building a line from the port city to mountainous Ronda with magnificent hotels at each end – the Reina Cristina in Algeciras and the Reina Victoria, in Ronda, which still bring hordes of tourists today. Aimed at giving the Gibraltar garrison access to the rest of Spain, the line stopped short of the Rock in Algeciras to avoid a confrontation with the Spanish government. In those days, a first class ticket from Algeciras to Ronda cost 17.10 pesetas. Today, it is often known as Mr Henderson’s Railway. His grandaughter Penelope Fleming recently died here, having lived for decades in San Pablo de Buceite, in Cadiz.

Sir Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming

In 1928, the Scottish biologist Sir Alexander Fleming famously discovered penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic. His newfound medicine would later save the lives of millions of people across Spain, many of whom were professional matadors. In gratitude, Spanish bullfighters erected a statue of Fleming outside the main bullring in Madrid, which still stands today. There are also streets named after ‘Doctor Fleming’ in almost every big city. The doctor himself is said to have visited Andalucia on various occasions and loved a glass of sherry. The great doctor once wrote: “If penicillin can cure those that are ill, Spanish sherry can bring the dead back to life.”

Kenneth Tynan

Kenneth Tynan

The British drama critic, playwright and novelist who opposed theatre censorship and was the first person to utter the F-word on British TV was a huge bullfighting fan. He attended over 80 corridas in Spain and wrote Bull Fever, regarded as one of the most eloquent English books on the genre. A view that could be seen as controversial today, he was impressed by the sport’s ‘love of grace and valour, of poise and pride; and, beyond these, the capacity to be exhilarated by master of technique.’ No surprises then that he was a regular visitor to watch bullfights in Ronda, but he also had quite a number of holidays in Mojacar, in an ‘obscure corner of Spain’, where he once got robbed and wrote about a string of vigorous, sex sessions with then lover Nicole.

William Mark

William Mark

Malaga’s singular English Cemetery owes its existence to the city’s British Consul from 1824 to 1836. Disgusted that while Catholics were allowed a decent church burial, British Protestants were disposed of on the beach – buried up to their necks in the sand – Mark successfully appealed to the Spanish government for a dedicated plot of land, now the oldest non-Roman Catholic cemetery in Spain. Visitors today will find the two lions guarding the tombstones of many influential people, a number of them British, in what is the quintessential ‘corner of a foreign field that is forever England’.

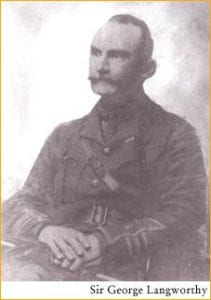

Sir George Langworthy

Sir George Langworthy

Known as ‘El Ingles de la Peseta’ (the Englishman of the Peseta) for giving away his fortune to local Andalucians, Sir George Langworthy died a poor man. Much of his wealth came from running the Castillo Santa Clara hotel in Torremolinos, one of the first on the Costa del Sol and certainly within Torremolinos, which opened in 1930. He is honoured as the town’s adopted son and is remembered for kick-starting the coast’s tourism industry. But best of all he is known for his extraordinary generosity that gave poor people help if they were starving, as long as they were prepared to read a passage from his bible. He moved here in 1890 and had first turned grief to charity after the death of his wife Margaret, aged 40, in 1913 shortly before the outbreak of World War I.

Thomas Osborne

Thomas Osborne

The famous Osborne bull which has become a symbol of Andalucia can be traced back to this Devonshire winemaker. Thomas Osborne Mann founded Bodegas Osborne in Cadiz town El Puerto de Santa Maria and today, 230 years later, the winery is still thriving. Born in Exeter he joined up with a large firm of wine dealers, Lonergan & White, in el Puerto and with another Englishman Sir James Duff they became key players in the Masonic Lodge in Cádiz.

Glyndwr Michael

More famously known as ‘The Man Who Never Was’, this drifter who died from eating rat poisoning played a vital but unknowing role in the fall of the Axis Powers during WW2. It is a fascinating story that saw British forces using his body as a decoy during 1943’s Operation Mincemeat in Huelva, dressing his corpse in the uniform of an Allied Forces captain and planting false documents alluding to an Allied invasion of Greece. Hitler fell for the subterfuge and, while Nazi troops moved into Greece, the Allies invaded through Sicily.

Hugh Matheson

Hugh Matheson

This 19th-century Scottish industrialist was founding president of the Rio Tinto Mine Company in Huelva. As well as becoming one of the world’s leading producers of copper, the company left a strong British legacy in terms of local architecture and leisure activities, including tennis and cricket (introduced for ‘men-only’ to prevent miners from having affairs with the locals). Most notably, in 1889 the miners formed the first football club in Spain. The uniquely British sport gained traction and within years there were clubs sprouting up everywhere.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

One of Britain’s most famous military heroes, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, also played a huge part in Spanish history. An influential participant during the Peninsular Campaign, he was the driving force in preventing France from invading Spain, yet his name rarely shows up in Spanish accounts of the Napoleonic Wars. This is thought to be because he heavily criticised Spanish soldiers later. He was however, gifted an estate after the 1814 peninsular war ended and the huge estate, knows as La Torre, has been used by the British royal family to hunt every since and his great granddaughter Charlotte Wellesley got married there last year.

Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce

King of the Scots from 1306 to 1329, Robert the Bruce promised to assist Spain’s King Alfonso in his war against the Moors of the Kingdom of Granada, but died before he could fulfil his promise. As a deathbed wish, he ordered compatriot Sir James Douglas to embalm his heart and wear it around his neck so that he could follow through on his promise. Douglas kept his word, emerging the victor against the Moors at the key Battle of Teba, between Antequera and Ronda, in 1330. He is said to have thrown the heart into the fray as he charged against the enemy army. The locket has never been found. This famous battle is still celebrated every year when hordes of Scots pay tribute to the Scottish pair at a special local feria in Teba.