THEY wore flowing black robes as a mark of distinction and represented a belief system that threatened the Spanish Catholic order.

THEY wore flowing black robes as a mark of distinction and represented a belief system that threatened the Spanish Catholic order.

They were deemed heretical, unbelieving and nonconforming and were eventually expelled from Spain en masse.

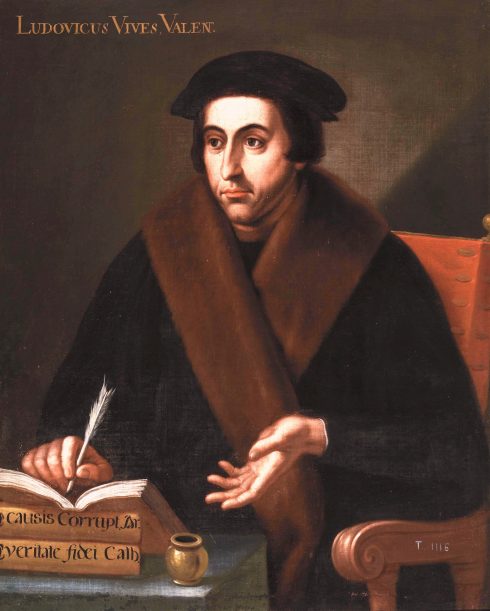

They were neither Moors nor Jews nor victims of the Spanish Inquisition. In fact, the Jesuits were devout Catholics. Just not the right kind of Catholics for 18th century Spain during the Age of Enlightenment.

They were forced into exile at a time when the monarchs of Europe – including and especially Spain – were taking a fresh look at religion.

It was a period of secularisation and anti-clericalism, when the fixed dogmas of the Roman Catholic Church were being questioned by science, individualism and philosophy.

In an attempt to centralise and modernise the country, Spain began to view The Jesuits, (unlike the Franciscans or Dominicans) as too autonomous in showing loyalty to the Crown. They were too international and too strongly allied with the Pope in Rome. Most threatening, however, was their economic success in the New World.

The Jesuits had become wildly successful in running plantations, mills, schools, hospitals and missions.

They had better business methods and, with exemptions from Royal taxes, they undercut other Spanish merchants and growers of tea, sugar, wine and cattle.

They had become too successful and, in the eyes of the Spanish Crown, a ‘state within a state’.

In 1767, a frightened King Charles III ordered the expulsion of The Society of Jesuits from Spain and the New World.

Troops assembled in churches, schools, monasteries and hospitals to march the Jesuits to points of embarkation and exile.

Within a year, the same fate awaited those Jesuits in Spanish America.

For the next 60 years, Jesuits experienced a type of diaspora with exiles settling in such diverse places as Corsica, Rome, France, Prussia and Russia.

It would be a mistake to assume that this ideological split within Spain’s Catholic hierarchy and the Jesuits is unique within religions.

Schisms like this seem to be the rule, rather that the exception. Within Christianity, the Protestant /Catholic divide is omnipresent. Just ask those living in Northern Ireland.

In Islam, the ideological Shia/Sunni split has been anything but seamless.

In Judaism, the secular/orthodox differences are daily issues within Israel’s body politic.

It would also be a mistake to assert that in modern times, Spain has been solidly Catholic.

Because, for a few decades in the 18th century, you had to be the ‘right kind of Catholic’.

The lesson here is that amongst human beings, the struggle over money, power and prestige seems to be a natural tendency, rather than a religion-specific tendency.

Humans beings are like that.

Click here to read more News from The Olive Press.