SPRING is the most beautiful time to visit the picturesque Genal Valley, when the almond trees are dressed in blossom like spring brides and the region’s world-famous chestnut trees are in bud.

This lush green corridor in the Serrania de Ronda is the largest producer of chestnuts in Andalucia, a business that brings in €10 million annually.

For those lucky enough to own a chestnut finca – and practically everyone who lives here does – money really does grow on trees!

The valley’s residents have long been secure in the knowledge that their 4,000 hectares of densely and meticulously-cultivated chestnut trees would be fruitful, year on year.

But maybe not this year.

Since a chestnut plague was discovered some 50km away in Juanar last May, fear has gripped the valley’s pueblos.

Catalunya’s and Galicia’s trees have already been stung by the killer wasps, but with less serious results as they produce a far lower yield of chestnuts.

The chestnut gall wasp (‘avispilla’ in Spanish, ‘dryocosmus kuriphilus’ to scientists) has the power to wreak economic and environmental havoc in the verdant Genal Valley.

The Genal’s residents witnessed the hasty cutting-down and incinerating of trees in Juanar, and fear the same will happen closer to home.

Francisco Saez, president of Jubrique and the Castanas Valle del Genal cooperatives, says the economic effects of the plague would be ‘very catastrophic.’

“We don’t know how intense the damage will be but we estimate the current income of chestnuts to be around €10 million for farmers alone,” he says.

The Valgenal cooperative factory processes up to 75,000kg per day and, given that 1kg sells for around €2, it’s a lucrative business.

Little plots of land guarded by high, rusty fences litter the valley floor, like a rural extreme of Cape Town’s post-apartheid gated communities.

Every Tom, Dick or Javier has chestnut trees. Down the generations, fincas have been divided between offspring, with more and more depending on the nuts.

One teenager who works the land shrugs when asked about the importance of the crop and says simply: “Chestnuts are the only real future.”

In Igualeja, there is a lot of frowning, head-shaking and gesticulating upon mention of la plaga. Everyone I meet wants to put their two cents in.

I am frogmarched to the town hall to meet the mayor, Francisco Escalona. He explains that the valley people await spring to discover if their fincas, too, have attracted the dreaded avispilla, which they suspect may be hibernating in their trees over the winter months.

When the new buds sprout on the leaves, it will become clear whether the insect has invaded, as chestnuts will simply not grow on the trees it inhabits.

Mayor Escalona has been extremely active in campaigns since the threat arose, and is under no illusions as to the destructive power of the plague.

“Nobody here believes that the plague is coming – they’re convinced it doesn’t exist. Nothing like this has ever happened before so they are in denial about it.

“They feel so far-removed from what has happened. On our own we have no way of combating it.

“Environmental experts are on call and set to analyse new growth and it will be down to the Junta to step in financially if action is called for.”

The Andalucian parliament has approved a plan proposed by Ronda’s PP party to fight the infestation if it strikes, headed up by coordinator Ricardo Dominguez.

The only known solution is the introduction of another insect – Torymus sinensis – as discovered by Turin University a decade after a chestnut gall wasp plague arrived in Italy.

As a parasitoid agent, it lays its eggs in the body of a ‘host’ insect and its larvae feed on it from the inside out.

Francisco Saez confirms that the Torymus, the natural predator of avispilla, has a 90% success rate in killing off the pests, while native parasites stand at just 20%.

Italy’s chestnut industry took a sizable knock when the insect, originating from China, was discovered there in 2002. Over a decade, it wiped out 70% of chestnut production in transalpine areas.

The wonderbug Torymus was introduced there in 2012, having achieved great results in Japan and North America in terms of crop rehabilitation.

In Spain, the damage could be catastrophic. Avispilla could wipe out 80% of produce in the Genal Valley and lead to mass deforestation from the burning of infected trees, necessary to reduce the chance of transmission. Each insect releases 100 eggs so the population can increase like wildfire.

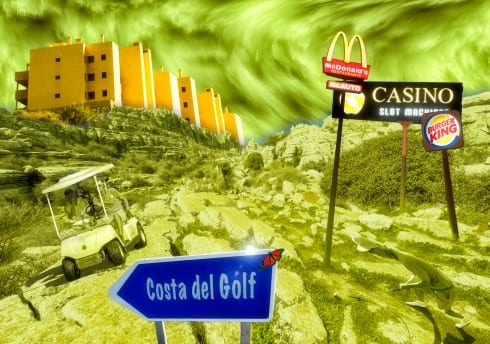

Many fear that a plague could be the final sting for the valley’s dwindling population, which has already lost many residents to jobs on the coast.

Igualeja’s mayor estimates his town’s head count has halved in two decades. Only 20 years ago, the primary school had 260 students. Now there are just 60.

“Our economy could only be saved by better motorway connections or investment as, currently, we are getting more and more isolated,” says the mayor.

In spite of his view that residents are in denial, everyone I speak to here is on tenterhooks: in small communities such as these, everyone will be affected if the crops fail – whether they are chestnut farmers or not.

Miguel Castaneda who owns restaurant El Nacimiento on the outskirts of Igualeja at the entrance to the valley, agrees that his restaurant would be in jeopardy if the crop failed.

“I don’t even have chestnuts but I would say 95% of this town benefits from the nuts and we would be totally lost without it.

“If money doesn’t come into the town, we will all suffer together,” he said.

In the neighbouring village of Pujerra, just a few kilometres away, some are convinced the plague won’t strike but others are sick with worry.

Ana, a cosy-looking woman whose children tend to her trees and attend crisis meetings at the town hall, says everyone is afraid. “Everyone is praying the wasps won’t come,” she says.

Lack of communication between the Junta and the residents mean they don’t know whether to burn their leaves over winter or leave them, and uncertainty reigns.

Ana’s companion tells me that, depending on the size of your finca, you can be making anything from €2,000 to €80,000 per year on your own chestnuts – not a figure to be sniffed at.

As I leave the village, a man called Diego bobs up and down on his tractor in the fading light.

His verdict is the most damning.

“The avispilla will come, I’m 100% certain,” he says with a wry smile of resignation.

“It will be like the potato famine in Ireland all over again. It’s just a matter of time.”

The next few months will bring the answers, but for now it’s a waiting game.