The link between countries and their ‘national dishes’ is culturally significant, yet look beneath the surface and the origins of your favourite dishes may leave a strange taste in your mouth…

A quick quiz…

What do the following word associations have in common?

My Italian grandmother’s tomato sauce

The Irish Potato Famine

Colombian coffee

‘As American as apple pie’

Spanish paella

At first glance, these groupings all associate an ethnicity with a food. They are all also, to varying degrees, misnomers.

Tomatoes are not intrinsically Italian. A potato is not synonymous with Ireland, nor is coffee with Colombia. Apples are not inherently American, just as the rice in paella is not Spanish. Furthermore, the foods mentioned above were all part of the ‘The Great Columbian Biological Exchange’ between Spain and The Americas following the voyage of Columbus in 1492. This event began a widespread circular introduction of a wide variety of new crops to both sides of the Atlantic. Allow me to explain…

Tomatoes are NOT Italian

In the 16th century, many Italians considered tomatoes poisonous. Italian physicians are said to have labeled them as ‘the generator of a melancholic humorous’. The first recorded European use of tomatoes as a sauce was in Spain in 1590. The head gardener at the botanical gardens of Aranjuez wrote: ‘it is said the tomatoes are good for a multitude of sauces’.

Biological evidence has determined that tomatoes are indigenous to central Mexico and found their way to the Iberian Peninsula via returning Spanish colonialists and conquistadors. The famous Italian combination of pasta with tomato sauce was only developed in the early 19th century.

The Irish Potato Famine

By the mid-19th century, nearly 40% of Ireland was under potato cultivation. Overdependence, a lack of genetic diversity, and a blight led to the Great Irish Potato Famine, in which nearly one million people died. Potatoes have become synonymous with Ireland, yet like the tomato, they originated in the New World, first domesticated in Peru and Bolivia between 8000-5000 BC.

They were recognised as an efficient energy source that could be stored for years. Returning colonial sailors first planted potatoes in Spanish soil in the 16th century and legend tells that Basque fisherman introduced potatoes to Ireland where they landed to dry their cod.

Colombian Coffee

There are more than 70 countries that grow great coffee, yet connoisseurs worldwide consistently rank Colombian beans among the world’s best. The country is so synonymous with coffee excellence that in 2007, UNESCO designated the Colombian coffee-growing region as a World Heritage Site – the first of its kind.

Archeological evidence suggests that the coffee bean was first cultivated in the Muslim shrines of Yemen as early as the 15th century. This sacred bean began to spread across the Muslim empire which included Spain. Jesuit priests and Spanish colonial settlers in the New World were quick to recognise Colombia’s coffee growing potential. Huge plantations sprung up and the legacy of Colombian coffee began.

‘As American as Apple Pie’

This common expression implies that apple pie is quintessentially American. Apples, however, are not even remotely so, in fact their origin is unclear. Some believe that apple trees were first planted, cultivated and harvested by the Romans but that their actual true can be traced to South Central Asia (Kazakhstan).

Like many of the aforementioned foods, apples crossed the ocean via colonisation, but here the plot thickens. One of America’s most enduring legends is that of ‘Johnny Appleseed’. The folk tale is that of an enigmatic, religious zealot (real name John Chapman) pioneering the migratory trails westward – planting apple seeds along the way. He believed that the consumption of apples gave humans a certain God-given spirituality that would await America’s settlement of the west. School children are told this tale and it is not a stretch to understand why apples are considered pure Americana.

Spanish Paella

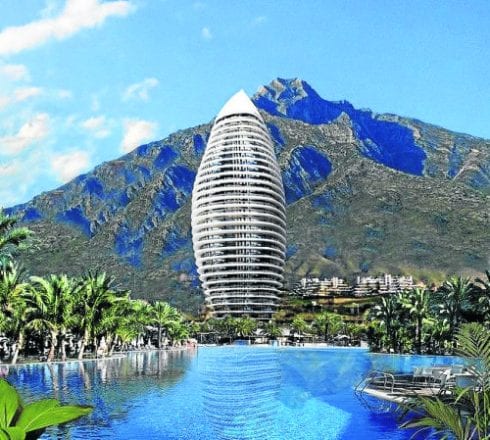

For many, paella is Spain’s national dish. It may be hard to believe but rice, the mainstay of paella, was a late-comer to the Spanish kitchen. Although not part of the aforementioned Columbian exchange, rice is yet another of the precious culinary gifts brought to Spain by the Moors.

For centuries it was a simple peasant staple dish. It wasn’t until the 18th century before actual recipes for ‘paella’ were referenced. The first recipe manuscript was found in the Episcopal Library in Barcelona, written by an anonymous compiler who drew a distinction between that which the Moors introduced and what we know as ‘paella’ today.

It slowly became a marvel of regional gastronomy and paella was picked up by the mass tourism sweeping the Spanish coastline in the 1960s and has been famous around the world ever since.

The Great Columbian Biological Exchange certainly involved much more than a mere transfer of a few food groups. Disease, livestock animals, weaponry, technology, religions and populations were also interchanged – often with disastrous effects.

So, next time you sit down to an ‘ethnic-specific’ meal, realise the food may represent a cultural heritage – an ethnology – more complex than you might think. What we call ‘ethnic foods’ reflect a rich culinary history that tells a larger story.

Most importantly though? Enjoy!