Matthew Pritchard asks if Spain will ever get over the 1930s, recalling his own personal connections to the civil war through his wife’s family

LAST month marked the 70th anniversary of the ending of the Spanish Civil War. Don’t worry if you missed it: the event was barely mentioned in the Spanish media. And this, of course, is not all that surprising. Because, although most of the people who actually lived through the conflict are dead or decrepit, the civil war is still a viciously divisive issue in Spain.

Part of the problem is that the Left and the Right today both cling to highly partisan versions of what actually happened during the civil war.

The left-wing version is all Republican democracy, heroism against the odds, International Brigades, la Pasionaria and cries of ‘no pasarán’. The executions, political purges and murders of clergymen are conveniently set aside.

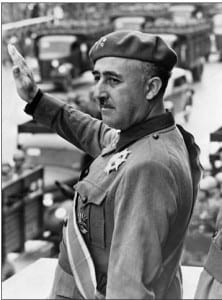

For right-wingers, Franco was a victim of circumstance, a brave champion of Spain, who was forced into action to save the country from the social upheaval brought about by the Second Republic. They forget that the chaos unleashed by Franco’s coup d’etât was infinitely worse.

Flags, songs and symbols from the time are waved around as much for the irritation they cause the ‘other’ side as for their actual meaning.

Details of executions and massacres are thrown back and forth across the political divide in a desperate attempt to prove that two wrongs do make a right.

Even on issues where the two sides could find common ground, the political will to do so is lacking.

Take my local city of Almería where there is a monument to 142 people from the province who, after escaping to France at the end of the civil war, were arrested by the Nazis and died in the Mauthausen concentration camp. Many of these were ordinary Spaniards, murdered by a universally-despised foreign power (Germany) and each May 5 there is an act held to commemorate the dead. Politicians from left-wing parties attend. But right-wing politicians stay away.

The fact that younger generations are a little hazy on the precise details of what happened doesn’t help either. Ideal newspaper in Granada described how the Student’s Union of Andalucía recently wrote an angry letter to a school in the town of Bailén demanding its name be changed from ‘el 19 de Julio’ as it celebrated a date related with fascism.

The bullets and bombs might have stopped but the war did not

The school’s director had to write back politely reminding them the civil war actually began on the 18th of July – the date his school commemorated was that of the Battle of Bailén, a famous Spanish victory over the invading Napoleonic forces.

But why has Spain, unlike most other European countries, failed to put its experiences in the violent first half of the 20th century behind it?

Firstly, Spain’s war was a civil one, with all the horrors that internecine conflict entails. But what really makes Spain’s case different is what occurred afterwards: As with Republican defeat the bullets and bombs stopped; the war did not.

The Franco regime was built upon a panoply of theatrical myths and central to this was the guilt of the Republic: it had been them, not Franco, who plunged the country into war and therefore they should be made to pay.Ghosts of Spain author and Guardian correspondent in Madrid, Giles Tremlett said: “There was a deliberate move to keep the wounds of the civil war alive. Part of this was a constant persecution of anyone who wasn’t openly for Franco.”

Under its infamous Law for the Repression of Freemasonry and Communism the regime encouraged a welter of denunciation that led to hundreds of thousands of people being imprisoned.

My wife’s grandfather was one of them and spent four years in a prison camp after a neighbour denounced him as a communist, despite not actually having fought in the war.

“They didn’t like him because he was a musician,” my mother-in-law told me. “Ironically, he wasn’t interested in politics when he went to prison. But he came out a member of the Communist party.”

This anecdote goes to the very essence of the problem. During the civil war itself, people had little choice as to which side they were on. The country rapidly fragmented into clearly defined zones of influence depending on which side won the initial armed struggle. Many people who had previously been ambivalent to politics found themselves branded Republicans by an accident of geography.

In the Spanish Civil War, pity, rather than truth was the first victim

But it was the repression after the war which caused these attitudes to harden into firmly held beliefs. Once people found themselves the victims of spiteful retribution for their perceived political allegiances, those allegiances often became reality.

What Spain is still struggling to overcome is not three years of civil war: it is three decades worth of resentment and bitterness created by totally unnecessary policies of persecution.

Of course, right wingers point to the fact that had the Republic won, exactly the same would have occurred: repression, executions, imprisonment. Depressingly, they are almost certainly right. In the Spanish Civil War, pity rather than truth was its first victim.

Spanish satirist, Mariano José de Larra, wrote: “Here lies half of Spain. It died of the other half.” Let us hope Spaniards in the 21st century can learn the truth of those words better they did in the 20th century.

One of the best stories I heard about the civil war was when two guardia civiles on horses asked my aunty who was 8 years old “Had she seen a man”. My aunty was doing her chores of minding the animals in the fields. My aunty directed them in an opposite direction and saved that man’s life. The next day my grandmother who was a widow with eight children was in her kitchen. The same man approached the kitchen’s window and told her that her little daughter saved his life and he left a considerable amount of money for my poor grandmother to feed her children and to buy a special pair of shoes for the little girl that saved his life. I have lived abroad a life time and all Spaniard were forever waiting for the death of Franco to return to their beloved Spain to live in democracy and peace. I think that the past has always wanted that part of Spain to die. There are some things that people want to take to their graves and not pass onto the next generation and there are things that people do what to pass onto next generations like hope. I believe that is what has happened to Spain.

Interesting article, can you suggest a good impartial book covering the events leading to the war, the war and the after effects?

Interestingly the British have appeared to produce more books about the Civil War than any other people. The granddaddy of all straight down the middle histories is Hugh Thomas’s hugh text ‘The Spanish Civil War’. It is as impartial as you can find on the war. More partisan reads from the ‘left’ are various the obvious being ‘Homage to Catalonia’ by George Orewll. Well written it tells part of the history from an non Communist Party view. There are any number of histories about the International Brigade. There are some new books oncluding one about the Scots who were there by Daniel Gray apatly titled ‘Homage to Caledonia’. (I had the privilage of knowing some of the men mentioned.)Anything by Preston or Tremlett.

An oddity, but very interesting, is Christopher Othen’s ‘Franco’s International Brigade’. It is an excellent read.

Hope this helps.

Cheers

Bob Cuddihy

oh……yes…..by virtue that pritchard married into a spanish family (rojo of course)…he now has lived the spanish civil war and is now an expert…… we are so lucky……

It is often forgotten that the British participation in the civil war was very even handed. While the communist inspired International Brigade are much talked about despite being only a token force the Friends of nationalist Spain were front line troops who took part in many battles. Franco’s personal bodyguard was a Yorkshire lad who joined the foreign Legion in 1934 and fought the war at his side before returning to England in 1939. Another group of prominent supporters of Franco were the many Irish soldiers who came. One reached the rank of general and was given a spectacular ranch near Alicante as a reward.

Many of these men were later to be distinguished during the second world, since their combat ecperience made them ideal officer material, despite the suspiscion that they had fought for the “wrong” side in Spain. In post war Britain people kept quiet about their actions in spain so only the loosers were able to boast about their time there.

Pedro Santamaria Grant requires a full response to his sadly ill-informed series of observations.

To suggest the International Brigades were a token force only is to misunderstand that the volunteers always “punched above their weight”. They numbered between 32.000 and 40,000 men. The men of the International Brigade, and those other volunteers from the British Independent Labour Party for instance, who fought with organisations such as the POUM, were deployed and thrown into battle as shock troops. Casualty rates testify to this. Their unfailing élan was considered more important than numbers or the shoddy equipment supplied to them, and as a result they paid a bloody price.

As to British even-handedness, the UK government’s adherence to the policy of non-intervention denied the legitimate government of Spain the ability to purchase arms and other war materials in the face of the fascist coup by the generals. A critical unintended consequence of this spineless policy forced the Republic to fall into the welcoming embrace of the Soviet Union.

The Friends of Nationalist Spain in the UK sent no front-line troops to support Franco. More to the point the Friends of Nationalist Spain sent no troops at all. Furthermore the organisation paled in comparison to the widespread public support for the Republic throughout the United Kingdom. Of the handful of British volunteers for Franco the most prominent was Peter Kemp who, interestingly, was a Protestant. He faced continual accusations of being a member of the despised Freemasons even as he fought for Franco. Frank Thomas is another who comes to mind and that is about it. There were a few nurses who travelled to support Franco but this limited medical support is as nothing compared to the countless doctors and nurses who arrived to support the Republic and tended the wounded of both sides. Setting aside the UK artists, writers and their ilk who rallied to the Republic, only one prominent literary intellectual supporter who could be considered a ‘British’ supporter would be the South African born poet Roy Campbell. However, despite allusions to front-line service by Campbell himself, there is no hard evidence this was the case. Campbell was certainly no John Cornford or George Orwell.

The most intriguing British contribution, and possibly most crucial intervention of the war, involved the carriage of General Franco to Tetuan in Morocco to rejoin the hardened troops of the Spanish Foreign Legion and the Army of Africa at the commencement of the coup in 1936. Franco had been posted to the Canaries by the Republican government; out of sight out of mind, but he remained in touch with the plotters. It was essential to the coup he rejoined his old command.

The money for the passage came from the Marques de Luca de Terra via Juan March – in his own right one of the most intriguing players during this period and subsequently World War II. Over lunch at London’s Simpsons- in- the – Strand restaurant a group of conspirators agreed the details of the mission. On July 18th 1936 a chartered two-engine de Havilland Dragon Rapid took off from Croydon Aerodrome bound for the Canaries piloted by former RAF Captain William Bebb. On board were Major Hugh Pollard, an attendee at the luncheon, and his daughter who was accompanied by a female friend. Pollard was an adventurer, a ‘former’ intelligence officer who eventually became MI6 Station Chief in Madrid in 1940. On arrival in the Canaries Franco joined the other passengers on board the aircraft wearing civilian clothes and having shaved his moustache off – fellow conspirator General Guei del Llano quipped this was the only sacrifice Franco made for Spain. Franco reached his old command and under his leadership they were airlifted across the Straits of Gibraltar by the Luftwaffe to mainland Spain.

I cannot comment regarding the Yorkshire bodyguard as there is no name or reference supplied. I would observe, however, Franco preferred to be photographed sitting at his desk flanked by a Moorish bodyguard, this from the protector of Catholic Spain. Clearly irony and Franco were strangers.

The battlefield disaster that was the Bandera Irlandesa del Terico was encouraged by Franco in the early days of the war only as a lure to the Carlists. Once a pact was agreed Franco wanted nothing to do with the Irish. In fact Franco had no time for foreign volunteers. The 700 odd Irishmen had been raised with the impassioned support of the Irish Bishops by the clerico-fascist founder of the Blueshirts’ General Erion O’Duffy.

Finally deployed in Spain in February 1937, despite Franco reneging on a deal to send a freighter to collect them, the Bandera Irlandesa deployed at Jamara. The second day of fighting saw the disillusioned Irishmen moved into a defensive position. Matters quickly went downhill in part because of the oily food and abundant cheap wine; a volunteer reportedly vomited down the neck of a Spanish general and the adjutant made off with the payroll. This sorry military mess ended with the Irish being withdrawn to Ireland in June 1937 a mere four months after their original deployment From this poorly led, ill disciplined, mutinous drunken rabble it would be interesting to know who it was who rose to the rank of general. There was only one Irish general involved, O’Duffy, who gained his rank in Ireland not on the battlefields of Spain.

In contrast the 200 odd men of the Irish Connolly Column of the XV International Brigade, the XV also included the British, Americans and Latin American Brigades, who fought heroically at Jamara and elsewhere. One of its leaders, former IRA chief Frank Ryan, rose to the rank of Brigadier. I doubt he was awarded a country estate by Franco. Some diminished remnants of the Irish Brigade joined the final parade of the Brigades in Barcelona in October 1938.

As to those who rose to distinction during World War II Peter Kemp was probably the most notable. Of course there was always Kim Philby who, under orders from his Soviet spy masters, reported from the Nationalist side for the Times newspaper having become close to the Friends of Nationalist Spain and the Anglo-German Friendship Fellowship, again under orders from Moscow, to enhance his future cover.

The only people to suffer on return from Spain were the Brigaders and others who had supported the Republic on the front line. Deemed premature anti-fascists they were hounded, spied upon and denied promotion during World War II and thereafter. Stalin also purged and murdered Communists who returned or were exiled to the Soviet Union from Spain, as they too were considered premature anti-fascists.

In my personal opinion the true losers were the tens of millions who died during World War II, the war the Civil War volunteers fought to stop. They foresaw the terrible price that would be paid if they failed to defeat the fascists and Nazis as they fought alongside the Spanish people and the Republic. Denied the tools for a legitimate defence by the elected Spanish Republican government against the fascist coup it failed in the face of the onslaught by tens of thousands of regular troops from Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, the aircraft of the Condor Legion that destroyed Guernica, and the ‘unknown’ submarines of the Italian Navy that sunk vital supply vessels. The terrible price they feared ensured the ruin of Europe for the second time in the 20th century.

Finally the contributions of the likes of the Friends of Nationalist Spain and the rest of Franco’s fascist sympathisers in the UK and Ireland were as nothing compared to the policy of non-intervention which, alongside the appeasement of the British and others, including Leon Blum’s French Popular Front government, towards Nazi Germany, encouraged Hitler to see his opportunity and he took it with both hands. As Spain descended into the Franco dictatorship Europe and the world descended into war.

During the war BOTH sides did horrible things. I think it is unfair that people only talk about the “horrible Nationalists”, when the republicans were much worse. Everybody knows about the bombing of Guernica, but shouldn´t we also remember that in 7 november 1937 the republicans bombarded the city of Cabra, causing the same amounts of deaths as Guernica, which, by the way, was bombed by the german Condor Legion dissobeying Franco´s orders, which said no harm should come to civilians? And there´s more.

The 13th of July 1936, BEFORE the war started, Jose Calvo Sotelo was killed by members of socialist militants. This was the reason why the rebelion started, although it would happened anyway.

The 19th of July of 1936 General Joaquín Fanjul Goñi and the nationalist troops he led surrendered after the republicans bombed their headquarters in Montaña de Madrid. The republican militias, violating international martial laws, took the soldiers’ personal belongings and shot them. About 200 soldiers were injustly shot dead after surrendering. Schlayer, a norweigan diplomat who was witness to the killings, said that “the new government, with noticeable lack of common sense, gave up their weapons, and with them, their authority”.

The 12th of August of the same year, 300 convicts from Jaen were killed in Santa Catalina as they came off the train, by republicans. During the war, the Republican government was responsible of most of the checas (groups formed by “milicianos” which exerted a strong repression against people, civilian or not, considered to be enemies of the Republic. They ilegally arrested, tortured and killed thousands of people. There were 331 checas). The most known checa was the “checa de Fomento”, which worked in nº9 calle de Fomento and was coordinated with the Dirección General de Seguridad.

The 22nd of August there was a fire in Modelo jail. Republicans took advantage of the situation and entered the jail. Other red soldiers started shooting at prisoners from the balcony. Inside the prison, prisoners were judged irregularly and those who opposed the republicans were shot.

Betwees the 25th of july 1936 up to the 26th of march of 1937 400 civilians from Las Ventas (Madrid) were murdered by republican soldiers.

In Boadilla del Monte, 166 bodies were exhumed. They had been killed by the milicianos. Only 25 were identified, of which 12 were monks and priests from San Juan de Dios.

In the cemetery of Aravaca at least 423 civilians were shot by reds, although the undertaker claimed there were 775 people killed. One of the killed was Ramiro de Maetzu, a spanish intellectual, who said “You don´t know why you kill me, but I know I die so that your sons will be better than you!”.

The Republican minister of justice Garcia Oliver, who had in his youth been a criminal, revealed the Government´s plans when he said “There are 10500 prisoners now, but in a few days there should be left no more than 500”.

In the Dirección General de Seguridad there was a list of prisoners to be killed. The communist Ramón Torrecilla mentioned between 20 and 25 “sacas”: 4 in the prison of Modelo, 4 or 5 in San Antón, between 6 and 8 in Porlier and between 6 and 8 in Las Ventas. Only in Modelo, about 1500 political prisoners were killed. Serrano Poncela, another socialist, referred to this as “final evacuation”. Prisoners were told they were going to be set free, and then they would be killed.

These killings were controlled and directed by Santiago Carrillo, who is still alive and has never been judged for crimes against humanity. He knew what was going on because foreign diplomats like Schlayer kept him informed, but he did nothing. The 11th of november of 1936 Santiago Carrillo signed an order under which the killings and the repression became legal and all sacas and checas were to be supervised by him. After that, between the 18th of november and the 4th of december, at least 363 people were killed in Porlier, more than 300 in Ventas, and around 1800 in San Anton.

The anarchist Melchor Rodriguez, also of the republicans, but a respectable man with a great respect for human life, saved the lives of thousands of people. He couldn’t stop the killing of 320 people in Guadalajara, but stopped killings in Alcalá de Henares, confronting the milicianos, Santiago Carrillo and the methods of repression of the government.

By the end of 1938 Stalin that Spain should become a one party communist dictatorship after the war. The president Negrín accepted. Two soviet documents back this up. “There’s no place for a return to parliamentarism. It would be impossible to accept the freedom of political parties like before.” “It is imperative that either a unified political organisation or a military dictatorship is implemented.”

The greatest killing committed by the populists was the killing of Paracuellos del Jarama. Antonio de Izaga, a witness, says 8354 people were killed. Ramon Salas Larrazabal states the number of victims was about 8300. De la Cierva thinks there may be 10000 people there. Only 2750 have been identified. The youngest person idenified was a 13 year old boy. Garzon was opposed to identifying bodies of this killing, as these were people killed by republicans.

In Torrejon another 2000 bodies were identified. 700 unknown were given a proper burial. In total, the populists killed 16000 people only in Madrid during the war. These people were divided into 7 common graves. Most of these victims weren’t even political enemies, but people killed by their religious beliefs. During the war, the populists killed 6832 religious people, of which 4184 were clergy, 12 were bishops, 238 were nuns, and 2365 were simply christian people.