Theresa O’Shea takes a tour of Malaga’s bandit country – the Axarquia range of mountains. Instead of highway robbery, she falls prey to the charms of the region’s white villages

IT all looks so peaceful and balmy. Empty roads essing their way past meadows, shiny and green with vines; white villages topped with red-tiled roofs and bell-tower churches; birdsong, cricket hum and perfect still. And of course, the paseros, the rectangular earthen boxes used since Moorish times for drying muscatel grapes into raisins. But it has not always been so bucolic. The lands and villages of the Raisin Route are steeped in a dramatic history of rebellion, resistance and renaissance. The evidence is everywhere: churches built on mosques, streets named after revolutionaries, battlefields and graveyards, museums that tell of epidemics and emigration, and an inn dedicated to highwaymen.

The Great Plague (Benagalbón)

Our journey starts at Benagalbón, one of the prettiest white villages in Andalucia, and just 5 kilometres from the coastal town of Rincón de la Victoria (12km from Málaga). It is a prosperous place, spotlessly kept, and with so much of a flurry of flowerpots that your eyes hurt. Deep purple, red, pink, yellow and lobster orange jump out at you at every step and the village square with its Arabic-style fountain in the shape of a star is filled with the scent of orange blossom.

Strangely, for a village of this size, there is no Town Hall – and this is the first sign of the area’s tumultuous past.

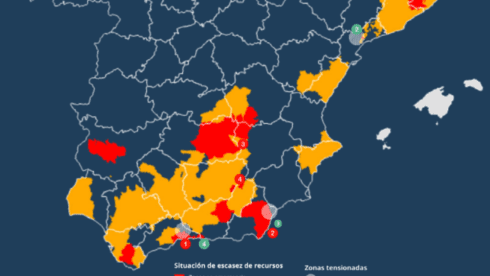

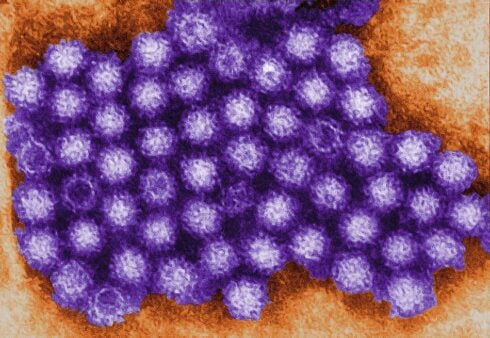

Administratively-speaking, Benagalbón belongs to Rincón de la Victoria. But it used to be the other way round – before the great grape epidemic caused by the phylloxera fly at the end of the 19th century.

Of all the villages on the raisin route, none were as badly affected by the “plague” (as villagers still refer to it) as Benagalbón and neighbouring Moclinejo. The crops failed. The once thriving area sank into depression and the exodus began: at first to the coast, where villagers found work as fishermen, and later to the other side of the globe. In the Benagalbón Folk Museum, a sepia photograph shows the village’s first emigrants in 1908, a young couple, smiling hopefully, about to take their free passage to Hawaii. Hundreds followed, mostly to the Americas.

Battle grounds (Moclinejo)

Leaving Benagalbón, we ascend towards Moclinejo, a larger more workaday village that makes its living from olive oil and muscatel wine production. As in all the villages dating back to Moorish times, the streets are narrow and shaded and the houses mostly one-storey with red-tiled sloping roofs.

The Axarquía was one of the last regions to fall to the Catholics during the Reconquest, and the inhabitants of Moclinejo in particular gave bloody battle. When forces from Antequera attacked the village in 1482, setting fire to the village, the Moors charged out of their castle, hurling tree trunks and rocks at the enemy. So many were killed that near the village there is a ravine called Hoyo de los Muertos (Pit of the Dead) and a hill named Cuesta de la Matanza (Killing Hill).

Grape Festival (Almáchar)

Between Moclinejo and Almáchar, raisin capital of the Axarquía, the road snakes under a shaded canopy of pine trees. To one side climb banks of almond and olive trees, while through the pines a mosaic opens up of brown fields and velvety vines, white cortijos and vegetable plots and raisin boxes, until at last the white houses of the village hove into view, strung out on a ridge like a slender bunch of grapes.

The name Almáchar comes form the Arabic Al Maysar, meaning The Prairie. When the Moors were expelled in 1497, they abandoned the fertile grape-growing land, which the Christians later co-opted and cultivated. To most Malagueños today, Almáchar is synonymous with ajoblanco – literally “white garlic” – but in fact a delicious cold soup made from almonds, garlic, bread, water and vinegar, and served with muscatel grapes. Sounds weird. Tastes great. Especially on a roasting summer’s day.

But ajoblanco is more than just a refreshing drink. To celebrate the prosperity of the land, every year on the first Saturday of September a grand Fiesta del Ajoblanco is held, where visitors can experience a soup (and raisins and sweet wine) crawl through the village’s historic quarter, visit the raisin museum, listen to verdiales groups, dance to musica pachanguera (popular music that is tacky but fun and performed by a group of Brotherhood of Man lookalikes), and around midnight enjoy an open-air freebie feast of grilled sardines and tinto de verano.

Bandit land (El Borge)

A grape’s throw from Almáchar sits El Borge, equally convinced it is the raisin capital of the Axarquía. Smaller than its neighbour down the hill, El Borge is my personal favourite, as much for its history of radicalism as for the views and the labyrinth of tortuous streets waiting to rip the wing-mirrors off your car. Don’t do it. Get out and walk. There are handrails to help you up the steepest streets and benches to rest on in the various flower-filled squares. Don’t miss the splendid 16th century church built on the site of a mosque.

El Borge’s radical past and present is well-documented. The town fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War and, after Málaga fell to the Fascists in 1936, republicans used the Axarquía as a base to carry out guerilla raids. There is a street named Republica and another one Che Guevara. When coalition forces attacked Iraq in 2003, the Town Hall (run by the left-wing Izquierda Unida party) declared an official day of mourning and banned all US products. More recently, the villagers missed the Royal Wedding of Prince Felipe when the mayor is rumoured to have unplugged the electricity supply!

But it is inside the Posada del Bandolero, the Bandit Inn and museum, that El Borge’s best legends abound. For the museum is a tribute to the infamous El Bizco de El Borge, the cross-eyed bandit of El Borge, and his gang. Regarded as Robin Hood heroes, during the second half of the 19th century the Cross-Eyed One and his merry men held up royal troops all over the Axarquía. The hotel-museum is a treasure trove of bandit memorabilia, housing a fascinating collection of posters from the many movies based on the era, muskets and gunpowder pouches, old documents and newspaper clippings, comic strips and other collector’s items. You can even sleep in a rustically-appointed room named after your own favourite highwayman.

Comares

Comares, the last major stop on the raisin route, perches on a rocky outcrop 685 metres above sea level, with the mighty Maroma mountain (2,065 metres) forming a snow-capped backdrop to the north. The Moors named Comares Qumaris, meaning “castle on high,” and the town was once of great strategic importance. Little remains of the Tahona, as it is known, but a rough-hewn turret up near the cemetery affords commanding views over the town and countryside. On the walls tiled panels tell the history of the area and the cobblestones are inlaid with mosaic follow-me footsteps. For the more energetic there are marked paths of between two and six hours that take you to outlying hamlets, springs and secret caves.

Our journey is nearly over. All that remains is to brave hearts and cars over the narrow mountain pass back down to the village of Totalán and the coast. As we leave the land of rebels and raisins behind, the views either side of rippling mountainettes, all mauve and green and sun-kissed, are worth every skipped heartbeat and millimetre of tyre-tread.

Grape and Raisin Festivals 2007

Saturday, 1 September: Fiesta del Ajoblanco, Almáchar

Sunday, 9 September: Feria de Viñeros, Moclinejo

Sunday, 16 September: Fiesta de la Pasa, El Borge

Places to stay

La Posada Bandolera, El Borge

Rooms 30€-35€ a night.

Excellent restaurant. A meal for two with wine around 40€.

Tel.952 519450

El Molino, Comares

Built on the site of an old oil mill, this hotel has a range of hotels, some with fireplaces and Jacuzzis. From 35€-85€. Tel. 952 2509309

Ajoblanco recipe

While I’m a dab hand at whizzing up regular gazpacho, my periodic attempts at ajoblanco have all ended up down the drain. The trick, I am told, is to always beat in the oil in the same direction to prevent curdling.

Ingredients

250g almonds (blanched)

2 cloves of garlic

150g white bread soaked in water and then wrung out

100g olive oil

1 litre of very cold water

3 tablespoons vinegar

salt

small bunch of Muscatel grapes

If you have the patience and strength of an ox in your wrist, grind the almonds, garlic and salt in a mortar. Add the bread until a smooth paste is formed. Then blend in the oil little until the mixture has a mayonnaise-type consistency. Mix in the vinegar, and finally pour into a large jug and add the water. Garnish with grapes and croutons. Alternatively, you can just whiz up all the dry ingredients in a blender, then blend in the oil.

Buenisimo Pepe, con uvas Moscatel es un manjar de Dioses. Cuando estoy en venaro en Malaga no me falta ni el ajoblanco bien fresquito ni el gazpacho.Creo que he visto alguna vez a mi madre comiendolo con higos frescos bien maduros, buenisimos.Un beso Pepe!!!