It is 40 years since the introduction of the civil war ‘pact of forgetting’ and Spain’s first democratic elections.

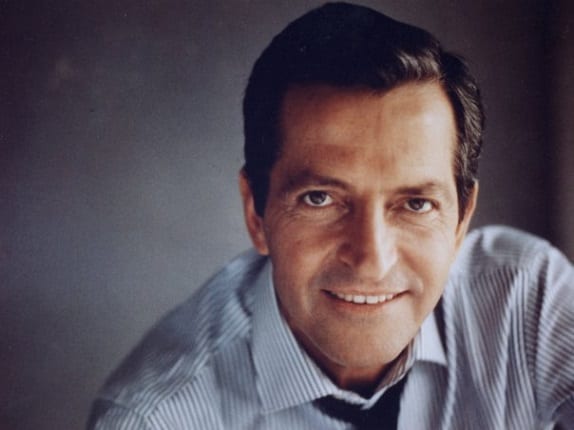

Here is the story of how one relatively unknown man became the country’s face of democracy.

HE was the architect of Spain’s transition from dictatorship to democracy.

Adolfo Suarez, Spain’s first democratically elected post-Franco leader, heaved the country out of its 36-year-long political winter into a promising spring.

A flurry of laws and legalisations disarmed unsuspecting Franco diehards, who were unable to react quickly enough to block the path to progress.

Political parties and unions were rapidly legalised, allowing Suarez to deliver the birth of a new democracy to the nation.

The Olive Press looks back on the man who helped create the Spain of today.

Route to power

The appointment of Suarez to the role of prime minister came as a shock to many.

As Secretary General of the Movimiento Nacional (the totalitarian body that wielded control over Spanish public life) and a loyal Franco employee, he was the outsider in a three man shortlist that many hoped would birth a progressive change.

The list was drawn up by the Council of the Realm, an advisory body of 17 almost exclusively strong Franco supporters, set up by the dictator in his dying days to ensure a suitable successor.

To many the leadership contest, the winner of which would be decided by King Juan Carlos, was a two horse show between apeturistas (liberalisers) Federico Silva Muñoz and Gregorio López Bravo.

But it was Suarez who was shoe-horned into the job eight months after Franco’s death in July 1976, following the resignation of Carlos Arias Navarro.

Initially appointed to succeed Franco, the latter had stood down after failing to pass any meaningful policies.

Suarez’ appointment was the culmination of many months of careful consideration by the king.

He had been bowled over by the Salamanca University-qualified lawyer’s plan to help society transition to a post-Franco system, alongside his belief that democratisation was inevitable due to current public opinion.

His combined knowledge of working within both a Francoist and post-Franco system, his relative youth (at 43) and his understanding of the need for rapid change, further emboldened the king.

First steps- La Transición

Within months of being sworn in, Suarez had proposed a tidal wave of reforms aimed at dismantling Francoism.

He wasted no time in forging a relationship with the democratic opposition and named General Gutiérrez Mellado as government Vice President to stop any chance of a destabilising coup.

It was not long before Suarez presented before the cortes (parliament) his Ley para la Reforma Política bill, a dynamite document that proposed universal suffrage and a bicameral parliament consisting of a congress and senate.

Perhaps most importantly, it also promised Spain’s first post-Franco democratic general election before June 30 1977.

Pressured by the weight of public desire for change and with no other practical option, the more right wing members of parliament were left with no real choice but to accept it in a vote in November 1976.

Perhaps the fact that Suarez made each of them in turn verbally cast their vote in proceedings broadcast live on TV and radio further pushed them to accept the bill, which they did by 425 to 59, with 13 abstentions.

The public had their say in a referendum on December 15.

The result was spectacularly decisive, with 94.2% in favour and only 2.6% against.

The new year brought with it another flurry of reforms designed to help facilitate the

much-anticipated election.

The socialist PSOE was legalised by Suarez’s government in February, followed by the Communist PCE in April.

Suarez recognised the right to strike and legalised trade unions. Notably, he also abolished the Movimiento Nacional, the very body he once headed.

The first democratic election

Following talks between the opposition regarding how the election should be conducted and votes counted, a date was set for June 15.

Yet, for Suarez and his government, one problem remained.

As they did not belong to any political party, their chances of being voted back into power were nil.

Suarez looked to the recently formed Centro Democratico, a party founded by Jose Maria Areilza, which he believed stood the best chance of garnering support from pro and anti-Francoists.

In a smooth negotiation, he convinced the members to ditch their leader in his favour, a move he argued would give them the best chance of winning the election.

So it came to be that the new Union de Centro Democratico (UCD), came to win the largest share of the vote in the polls, at 34%.

But they were to face stiff opposition in parliament from the socialists, who entered its chambers with a sizeable 29%.

The Communists and the Alianza Popular had less success, winning 9% and 8% respectively.

New policies for a new political dawn

Keen to avoid unbalancing the new, fragile democracy, Suarez set his focus on stabilising the economy which had been in crisis since 1974.

The resulting Pactos de Moncloa was viewed as a veritable olive branch between the different parties.

Wrangled over, voted on and approved by the parliament, it included a wide range of economic measures designed to reduce inflation and tackle the national deficit.

Among them were policies to encourage wage increases, devaluation of the peseta, reform of the tax system and control of the financial sector.

Politicians on the left were won over by measures that entrenched the right to union membership, freedom of expression, press freedom and the right of assembly.

Buoyed by the promise of a new era of liberalism following Franco’s death, the cries of political regionalists, silenced for so long, began to grow loud.

In re-establishing the statute of autonomy, an act brought in by the pre-Franco Republican government, Suarez could not ignore the demands for self rule coming from Catalunya and the Basque Country.

But he chose instead to make contact with the exiled Josep Tarradellas, President of the Catalonian Generalidad (regional government), in a bid avoid having to re-introduce the same level of autonomy.

Tarradellas returned to Barcelona after the provisional re-establishment of the Generalidad , which did not, at that point, wield much real power.

The aim was to try get the population used to the idea of having a regional parliament before the creation of a new Spanish constitution, which would enshrine them in law.

Unveiled in 1978, the long and vague constitution was a testament to the variation of political opinion within the parliament.

It declared Spain a parliamentary monarchy with no death penalty, no official religion and a voting age set at 18.

Its major selling point, however, was the agreement of autonomy for regions.

Those that could meet a set of predefined requirements would be able to enjoy their own president, government, legislature and Supreme Court.

Through them, the constitution allowed them to exercise power in areas such as housing, health and social services, agriculture and town planning, provided that they met with the broad direction of central government policy.

Those three regions with ‘historical nationalities’ – the Basque Country, Catalunya and Galicia – were given the right to achieve autonomy by simply signalling their desire for it.

The rest had to win the support of more than half of voters in regional referendums, and in reality enjoyed a mixed bag of autonomous powers.

In between 1979 and 1983, a total of 17 autonomous regions were formally recognised through the law, creating the modern state we know today.

El Pacto de Olvidado (the pact of forgetting) is perhaps one of the most controversial of all the major laws brought in under Suarez.

Enacted in 1977, it gave amnesty to those responsible for crimes against humanity during the Franco era, including forced disappearances and genocide.

This allowed them to continue on without punishment, often in roles of power they had first gained through their active Francoist role.

Parliament’s aim was simple – to put the past behind and focus on the future of Spain.

While many historians have accepted that this ensured the survival of democracy at the time, failure to subsequently repeal it has drawn repeated criticism from international bodies such as Amnesty International.

The lack of a thorough investigation into the heinous war crimes committed during the era has also unwittingly served to compound an element of historical confusion among the public.

Suarez’ demise

A further general election held in March 1979 returned the UCD to power, yet again as a minority government.

But the election marked the beginning of a period beset by political, social and economic difficulties for Suarez, leading to his resignation.

One month later the left had its first decisive victory in the first democratic municipal elections, allowing socialist and communist takeovers of town halls.

That year’s petrol crisis left one million people out of work, while the resurgence of Basque terrorist group ETA led to 179 deaths during 1979/80.

As a result, political differences grew more pronounced.

Suarez was denounced for his lack of reform in areas such as the judiciary, police, army, schools, health and welfare and his failure to legalise abortion or divorce.

He was also lambasted by the Left over his desire to sign Spain up to NATO, finally accomplished in 1982.

In 1980, the PSOE attempted to impose a motion of no confidence. Although it failed, it deteriorated the image of Suarez among his own team.

Thus, it was not a surprise to many when, on January 29, 1981, Suarez presented his resignation both as prime minister and party leader.

In a speech on Television Espanola, he explained: “I do not wish that, because of me, the democratic regime of coexistence should once more be a parenthesis in the history of Spain.”

One month later, Suarez was conferred the highest honour possible by King Juan Carlos – a dukedom.

An accomplished crisis manager who steered Spain through the dangerous waters of the post- Franco period, Suarez either lacked the desire or ideology required to remain at the helm.

Simple, Franco died but as the article states correctly the judiciary/armed forces, the whole apparatus continued on as normal up to and including today. The camouflage is good but not that good.